By Adagbo Onoja

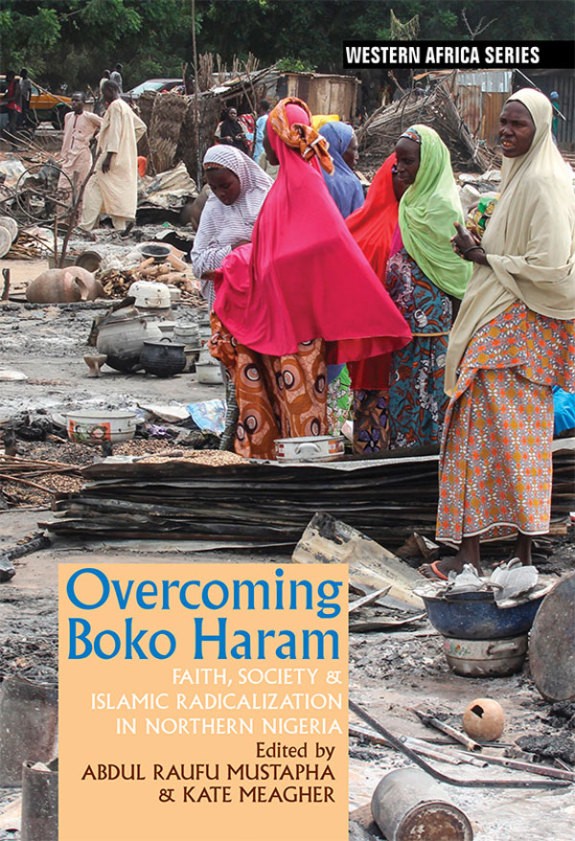

A hopefully passable revisiting of the August 19th, 2020 webinar on Raufu Mustapha and Kate Meagher’s edited work Overcoming Boko Haram: Faith, Society and Islamic Radicalisation provides the warrant for this dangerous exercise. That is, dangerous as far as the reporter has not read the book itself but warranted by the belief that revisiting should also hopefully expand the audience of the event as well as the book. The assumption is that the risk of careering off too far may not be much after listening to Dr. Kate Meagher who completed the work after the demise of Prof Raufu Mustapha, her late husband.

Dr. Kate Meagher, co-author of the book

On that note, there might be no better starting point than Meagher’s revelation to the effect that Raufu once said the question of Boko Haram is the first thing that had ever shaken his faith in the survival of Nigeria as a country. As the wife and co-author, that must be the ultimate unimpeachable self-reporting. The greater the value if she had gone ahead to say why Raufu said so. In the absence of that, it is important to attempt filling the gap. The reason might not be any other than the pain of a scholar witnessing a reality that Raufu Mustapha can be credited with predicting, in the broadest sense of prediction. He did predict Boko Haram when he disagreed with the notion that the Nigerian Civil War had resolved the National Question and associated threats. As opposed to that position, he argues that “The Civil War did not resolve the National Question. What is true is that the Nigerian State was able to overcome a specific challenge to its integrity. This does not, however, mean that no future challenges are probable, or that the state would always have the capacity to overcome such challenges. The emergence of Anya Anya 11 in the Sudan is a case in point. The unity of the country cannot, therefore, be necessarily guaranteed by the state as currently constituted”

In fact, in this 1987 prediction of Boko Haram, Raufu went beyond probablism because it has been too precisely formulated. His conclusion came from things that were happening on the ground, what he called “events in Nigeria since 1983” and he listed a number of them as ‘the No Nation! No Destiny! broadcast of the FRCN Kaduna; the acrimonious and chauvinistic campaigns associated with the 1983 elections; the incessant disputes over the question of Federal Character; and the debacle over Nigeria’s affiliation to the Organisation of Islamic Countries’ all of which he saw as tending ‘to suggest that the unity of the country cannot be taken for granted’.

He was not an empiricist but he still had his ears to the ground as to be able to, as Yusuf Bangura correctly observed about him, branch out of primary/secondary contradiction binary and begin to see that identity politics and the accompanying ideational/constructivist fireworks is where the danger lies. The problems may be economic but it is language in which it is framed that embody the meaning of it for those who suffer the worst of privations but who are also those who lack the intellectual resources to frame their reality in terms of structural contradictions.

This background makes the scholarship in Overcoming Boko Haram a final confirmation of the Early Warning that was not acted upon. It is worrisome at two levels. The first is the general and specific aspects of Meagher’s presentation. The general is the analysis that understands Boko Haram as an outcome of how colonialism and independence created distinct types of religious politics in Northern Nigeria rather than a question of one region being better handler of religious identity conflict. The specific is the assertion that the insurgency is a product of political competition and social protest in a Muslim majority context. True or not, these must, in themselves, be troubling for anyone concerned with stability in a multi-everything society such as Nigeria.

The second worrisome aspect must be that the webinar was not a state function or that there are no widely publicised seminars or review sessions on the book across the country. Perhaps, there might not be much to expect from the universities which are perpetually shut but whose departments of International Relations, Peace and Conflict Studies, Mass Communications, Cultural Studies, Political Science, Sociology and Anthropology, Geography and Linguistics should have been the main sites for ‘reading’ the book. But what of the military, The Presidency, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, of Interior, the key military academies, the state-owned think tanks, (NIIA, NIPSS, IPCR, NDA and so on. It is possible that the COVID-19 crisis has made it impossible since February when the book was released and that such are in the pipeline. That would be great if they are and for the good reason that apart from the level of analysis, Raufu is not another scholar pontificating about Nigeria from a distant Western intellectual space. He was as organic as they come, a claim that should not go without illustration.

This story has been told before but would be repeated here to demonstrate that Raufu was not an unconscious example of brain drain. In 2000 when businessman George Speight staged a civilian coup in Fiji Island, Sule Lamido, the then Nigerian Foreign Affairs Minister, needed more than the information immediately available because a Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group, (CMAG) meeting had been called. On arrival in London from a different assignment to wait for the meeting, I said I could think of someone who could fill the gap in a manner satisfactory to the minister. He is Dr Raufu Mustapha at Oxford University. Call him, came the minister’s approval. In a few minutes, I was on the line with him. The minister has asked me to ask you to report here. I wanted to annoy him by conveying the request in the commandist tone typical in Nigeria but he surprised me by saying that the Nigerian Minister for Foreign Affairs could summon him anytime, anywhere once both were outside Nigeria because, in such cases, it has become a call to duty. The only problem was that the earliest time he could be in London would be noon the following day. That was very okay since the meeting was still two days away. And he did come and there was a beautiful interaction. Before his arrival, the minister had said I would take him to lunch after the discussion. However, the minister changed his mind after the discussion by saying he would take him to the launch personally. In doing that, he robbed me of opportunity to host an Oxford don to state paid lunch.

The late Raufu Mustapha

This is just by way of the background. The more important thing was the question Lamido posed to him at the lunch. Why would a brilliant Nigerian be at Oxford and not somewhere back home, teaching Nigerian youths, said Lamido. The children you are teaching, said Mister minister to Raufu, are those whose future in the world today is already secure unlike those ones back home. It was a tense moment. Raufu’s answer is that he tried to do exactly what the minister would have wanted but teaching in Nigeria in general and in ABU, Zaria from where he left to Oxford had become impossible. He gave a few examples that weakened Lamido’s obvious resolve to press on. Of course, Alhaji Lawal Batagarawa, the then Minister of State for Education who was also at the lunch was not comfortable with some aspects of Raufu’s narrative and did offer a challenge. a debate did ensure between the two.

Lamido who is not aware of the tendency gulf between Batagarawa’s PRP intellectuals and Raufu’s Zaria Group in the great split among the ABU, Zaria radical basement jokingly overruled Batagarawa in favour of Raufu. In a way, Lamido was right because, apart from Raufu, all but one of those ABU, Zaria sent out to obtain their PhD outside the country, have since left or been made to leave the university. Apart from Raufu, there is the Jibrin Ibrahim case. The case is not so much that he is not in Zaria anymore but that the Nigerian State is not asking how a PhD holder in Political Science from a French university is very much around but not attached to any university. And this is happening at a time when only few universities can actually talk of a credible Dept of Political Science. How can you beat Boko Haram back if you can take stock of your human resources? As joyous as the lunch, that aspect of the conversation had touched odious aspects of Nigeria: division everywhere, even among hard headed radicals and how nobody appreciates that a nation must shield its universities from the vagaries of politics?

Insisting on attention to the book on the ground of the exceptionalism of the authors automatically raises the question of what is to be taken most seriously about the book. It would appear the authors anticipated this by the title they chose: Overcoming Boko Haram. Again, as Meagher put it, the objective was to inform a more socially engaged approach in contrast to counter-terrorism. It is the question of how to overcome the insurgency that brought about looking at what gave rise to it, why it did not start in an epicenter of Salafism such as Kano but in a rather quiet corner of Borno but only to fail to take roots in Southern part of Niger Republic which is contiguous in all regards, what is the role of poverty in it all of it and what the endgames could be.

None of the four book reviewers at the webinar disagreed with the view that Boko Haram is not an Islamic movement but a movement for which Islam is only serving as the idiom for re-imagining utopia in the classic sense of the word. It is thus not a typical global Jihadist actor but a disaster “in the politics of state capture, religious brinkmanship and popular disaffection in a Muslim majority context”. That is, in Boko Haram, Nigeria confronts the political use of Salafism for state capture within the scope of a context of self-learning: self-trained, self-aught preachers looking for followers in the crucible of struggle for political power in the era of botched Sharia. But also in the era of the worst intra-state and inter-regional inequality in that while the Human Development Index for Lagos State is at par with India’s, that of Borno State is at par with Afghanistan’s as in 2010. Only those who have read the book might make better sense of why this is brought in, given the disapproval for the poverty-terrorism nexus, the most widely cited example being how ETA could develop in Spain which is highly developed by any standard of measurement.

Prof Kyari Mohammed, himself an authority on Boko Haram and one of the four reviewers, does not accept a number of things about the book although he says it is the best of the materials on the insurgency so far. The Vice-Chancellor of the Nigerian Army University, Biu thinks there is a problem of writing on an on-going phenomenon to say that Boko Haram has failed to take place in Southern parts of Niger Republic. This is an issue considered important because, as Dr. Abdourahmane Idrissa of Leiden University in the Netherlands who is also researching the problematic of Islam in developing world puts it, Southern Niger is practically a part of Northern Nigeria where the Nigerian currency and religious education always dominated. Prof Kyari says the insurgency is now entering places like Diffa and Bosso and it is too early to say so. His second point of disagreement is that centralism in Niger Republic as opposed to federalism and a relatively weak centre in Nigeria does not explain why Boko Haram has not been such a reality in Niger Republic. His third disagreement is with a pacificist Sunni/violent Salafi binary and lastly, the need to take agency more seriously. Simply put, he is saying that there was a Mohammed Yusuf in Borno which was not the case in Southern Nigeria but that we need to watch it because a Kaka Bunu is already in detention in Niger Republic. That is, with agency, anything could happen up there in Southern part of Niger Republic.

For Dr. Abdourahmane Idrissa, the third reviewer, there is a geo-strategic reason by which he means that the very large, flat, arid, windswept territory into the Sahara Desert discourages the brand of terrorism/guerrilla warfare that Boko Haram practices. Culturally, Boko Haram messages are stronger among the Kanuris in Diffa. In fact, he argues that “the integration of Diffa and Borno is a Kanuri integration”. That is to suggest the differential impact of the Boko Haram messages in Southern Niger. Sociologically, his explanation is that there are less social contradictions in Southern Niger for the invocations of Boko Haram to strike deep. Diffa is less urbanized and the people are materially poorer, he said.

Taking all these into consideration and noting how the home-grown, anti-state religious movement has become more like classic complex emergency, with links to ISIS taking roots, a harvest of a war economy and the insurgency becoming ATM for military and state corruption, the authors made their proposal on how to end the insurgency. That proposal and the interesting submissions of Dr Fatima Akilu should constitute the concluding part of this report.