Dangerous Moment in Nigeria’s Anti-Corruption War

Ibrahim Magu: In the eye of storm

The last two days of 2016 were full of ‘news from nowhere’ around Ibrahim Magu, the acting chairperson of Nigeria’s anti-graft agency. It is in the nature of ‘news from nowhere’ to be such that even the presidency could not be that categorical on December 31st, 2016 in responding to the inquiries on the ‘story’ circulating that the acting chairperson had been sacked. Mallam Garba Shehu, one of the presidential spokesmen, said it was speculative and pre-emptive, thereby confirming high tension politics over the contested candidature of the current but not the substantive chairperson. It was only the news of Ibrahim Magu’s visit to IDP camps that day that must have halted people crying or jumping up for joy over the ‘sack’, depending on where each person stands on his fate. That false flag via a story of the purported sack of Magu on December 31st remains the clearest evidence that his appointment has become the hottest item in the politics of power in Nigeria at the moment. How it ends will reveal a lot about who/which group in the constellations around power is the most influential as well as the future of anti-corruption war in Nigeria.

SGF Babachir Lawal, a suspect cabal actor in the politics of anti-corruption war

It has been a long walk to confirming or not confirming Ibrahim Magu as EFCC chairman and which has produced a puzzle already, however it goes. It has been a long war, starting actually in the Presidency but becoming most manifest at the Senate between the forces for and against Ibrahim Magu. A police officer who had paid the price for principled obstinacy before in the fight against corruption, Magu had had been on the job in acting capacity for a year plus by December, 2016. Things had to begin to happen regarding his confirmation. But when it did, the Senate told the world it could not confirm him because a security report emanating from the Directorate of State Security Service, (DSSS) had some black dots which could not be overlooked. Subsequently, Abubakar Malami, the Minister of Justice and Attorney-General of the Federation was put at the head of a team to investigate what those black dots in the eyes of the Senate could mean. By sending the case file for further works, the president was saying that whatever it was that the Senate was saying could not be waived aside.

Taking charge?

In other words, who knows what information the president has as to be unable to wave aside the reservations of the Senate? After all, the president just gave Bukola Saraki, the Senate President, an ‘A’ rating in the hall of the powerful in Nigeria. From that moment, any verdict could be delivered on Magu. If Magu, therefore, gets back the job, he would be reversing the trend of messy departure for chief executives of EFCC ever since. If, for whatever reasons, he doesn’t get it back, he would have reinforced the trend. At the moment, only God and perhaps President Buhari would know which one it would be.

Reinforcing the trend simply refers to the unique risk factor in EFCC chairperson’s seat. The dialectics of fighting corruption is such that creates anti-theses which ensures that the chairperson’s departure is always messy. Nuhu Ribadu, the pioneer chairperson left in that manner. He became the prey of those he preyed on before and he was lucky to depart with his life intact. They pursued him up to the National Institute of Policy and Strategic Studies, Jos where he was initially eased out into in late 2007. He had to leave the country. His story bears a striking similarity with the Biblical narrative of the fate of the iconic Joseph unknown to a new Pharaoh. Obasanjo, the old Pharaoh, knew this Joseph very well but not Umaru Yar’Adua. Well, not as much, perhaps not after whatever brushes Ribadu might have had with Yar’Adua in the course of the anti-corruption clockwork on public officers, of which governors were top.

Ribadu: Came under fire, followed by a messy departure as EFCC Chairman

Then Ibrahim Lamorde took over in acting capacity until Farida Waziri was appointed mid 2008. It was one damned controversy after another until she was eventually removed in 2011. That, in itself, was traceable to power struggle. Or what would now be a case of ‘corruption fighting back’. Waziri was succeeded by Ibrahim Lamorde, the eventual arrival of one who had been the ‘deputy’ since EFCC was born. Lamorde carried on till his exit in 2015. By this time, he had already been drawn into court brawl with the Senate. Against this background, Magu’s fate could be another in the drama series that constitutes the tradition of departure of EFCC chairpersons from that office.

Whichever one turns out to be the case, it would be impossible to divorce it from corruption fighting back. The puzzle this time, however, would be the nature and location of the corruption that fought back. Is it corruption within or outside the presidency? If it is outside the presidency, is it to be found in the Senate or simply in a yet to be determined location? Or, is it even outside the country entirely? After all, according to Nuhu Ribadu, “Nigeria lost billions of dollars stashed in foreign banks or invested in opulent mansions in European capitals”. This, he said, privileged the EU, the UK, the United States and the World Bank in EFCC’s successes under him. So, it would not be that shocking if big companies that underpin grand corruption came together.

David Cameron, the former British Prime Minister who threatened fire and brimestone on corruption in Nigeria @ the WEF in 2013

Beyond the stalemate over Magu’s candidature, the attendant high tension politics and the puzzle hanging over it all now, there is the question of the crowded hall of the anti-corruption armies, leaving the point of convergence as opaque as it can be. The World Bank and the Nigerian government do not understand corruption from the same perspective. Yet, they are in it together. Investors have a broadly neoliberal perspective but they do not look at corruption from the same lens as the Nigerian government or from that of the World Bank. They too constitute an army in this war. Same as the global/local civil society which equally has a neoliberal conception of corruption but with a tinge of ‘the multitude’ or the Occupy Movement radicalism. They are, therefore, a standalone army against corruption from that perspective. There is a swath of mainly dispossessed middle class elements who, by their locale in the social set up of Nigeria, do know how money have been moved around and by whom. They constitute an angry bunch out there in favour of the anti-corruption war. Finally, the moral army led by president Buhari himself as anti-corruption enthusiasts from the perspective that corruption is morally reprehensible. Entrapment in dogma, leading to de-politicisation of the war, makes it the weakest of the anti-corruption armies although this is the source of the most vociferous condemnation of corruption.

The 2016 anti-corruption conference in London as one plank

Each of these armies has its own perspective and, in the field, it is difficult to see the point of convergence at the level of the grand strategy. Yet, by the day, the forces being fought manifest a tougher grasp of the war than the anti-corruption armies. What are they trying to achieve? Are some of the armies not fifth columnists, in an ideological sense?

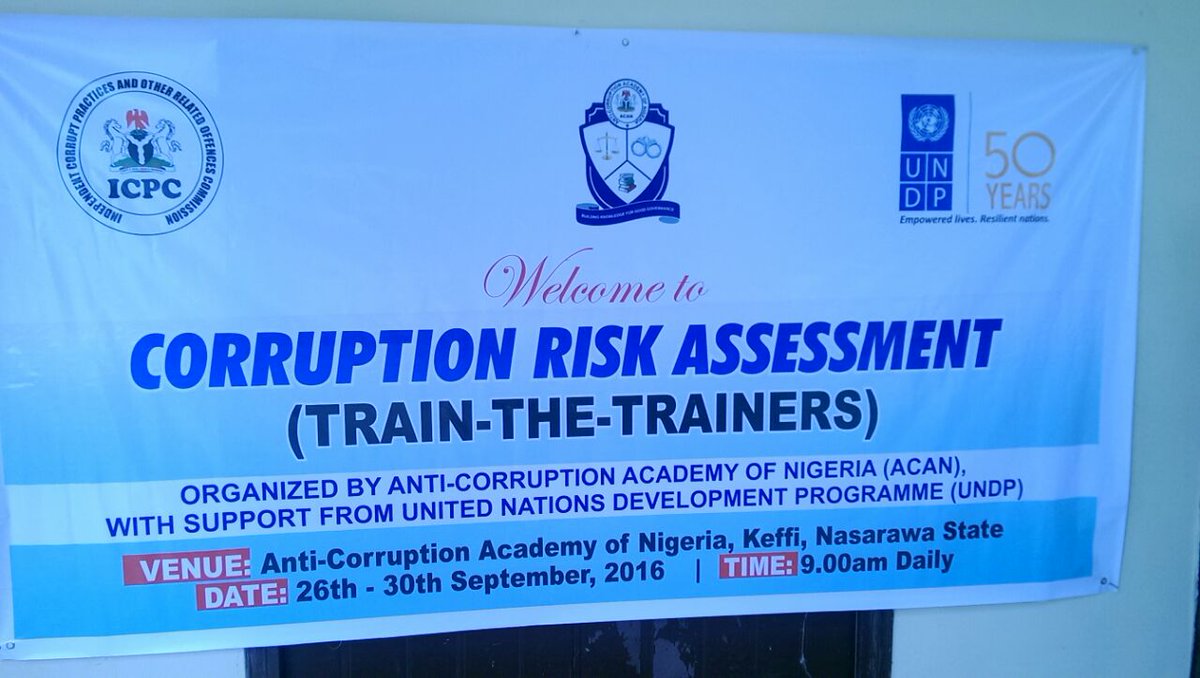

At the institutional level, it looks crowded too. There is the EFCC, the Code of Conduct Bureau (CCB), the Code of Conduct Tribunal, (CCT) and the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission, (ICPC). These are besides residual sections in the Nigeria Police, the DSSS, the Ministries of Justice, Finance and sundry institutions. Is it not possible to hierarchically arrange and harmonise these under a central corruption bursting agency?

Gentlemen, is it possible and/or desirable to have one anti-corruption house?

Corruption is an ugly but complicated reality. What to do about it and how best to do it is one of the toughest questions to ponder on today in Africa. Nuhu Ribadu, for instance, has an unbeatable argument why corruption must be fought: “The famed writer Chinua Achebe reminds us that in every journey of discovery, the critical point of departure is from where the rain started beating us. Thus in the face of the palpable institutional decay around us, and in the grim reality where about 70% of 120 million Nigerians live in hopeless poverty, all these for the world’s fifth oil producing nation, there must be something paralysing if not breathless about the notion and comprehension of governance that is characterized by the squandering of our huge human and natural resources”. His is a supportable critical political economy perspective. But why is everything so far throwing up a situation whereby corrupt forces are stronger than those fighting it? Proof of this claim requires no more than the current situation whereby the appointment of the soul of the campaign could become infected by corruption or shadows of corruption. Worse still, it comes with the puzzle cited above regarding where the corruption that is fighting back in the appointment of the chairperson of EFCC can be located. It is a complicated puzzle because it is evidently located in the presidency, whose actors are the ones at work in the stalemate over the appointment.

‘Adoptee’

There is clearly a problem somewhere, the resolution of which might start with clarifying the organising concept itself – corruption. Is it corruption or graft that is being fought? Can this regime fight corruption, what with its slender social base and an apolitical approach to a very political issue as corruption? Where are the masses in this struggle or they don’t count? The dialectics of capitalism, more so the variant of capitalism in Nigeria (doubtful if it has got a name) is such that the anti-theses of a war against corruption can be messy if understood and conducted mechanically rather than seen from the perspective of the power relations it expresses. In the absence of elite consensus, nothing less than a mass movement can fight corruption in this country. What we are seeing in the debacle over Ibrahim Magu’s appointment attests to that.