By Yusuf Bangura

A few days ago, we talked about the uniqueness of each of the four countries we visited and the amazing people that made our tour enjoyable. We want to conclude these reflections by addressing three issues that we believe left an indelible mark on us.

These are: i), the obscene legacy of racial segregation and dehumanization of black lives in Namibia and Cape Town; ii) Botswana’s incredible transformation from a beggar nation to an upper-middle-income country within a timescale of 39 years; and iii), Ethiopia’s rich cultural heritage and unrivalled sense of independence.

*Memories of truly remarkable places*

But before we discuss these three big impressions, let’s first relieve the memories of some of the truly remarkable places we visited.

The two-hour drive from Solitaire in central Namibia to Sossusvlei, where we visited Deathvlei, the sand dunes and the Sesriem canyon, was breathtakingly beautiful. I don’t think we have seen a more stunning landscape in all our travels in Africa and, perhaps, the world. The wild combinations of arid and semi-arid landforms; the changing rock formations and vegetation; the incredibly bright, sprawling and imposing sand dunes; the awesome ocean view; and the kilometre-long canyon at Sesriem were utterly mesmerising.

Cape Town’s Table Mountain, which serves as a backdrop to the city, and the eight-kilometre cape peninsular road of stunning beaches as well as the irresistible Water Front were unforgettable.

Despite the blighted nature of Katutura township in the Windhoek area, it was great to visit the popular, semi open braai kapana fire grills and join the local inhabitants to eat well grilled strips of meat and *oshifima*, or fermented dough, served with the traditional drink, *isukuma*. Isukuma tasted very much like the famous *kunu zaki* of Northern Nigeria.

Camping at the arid landscape of Damaraland in Namibia, spending almost a whole day elephant-tracking, and joyfully interacting with the Himba people in their traditional village setting were a novel and treasured experience.

In Botswana, our 12-hour safari at the Okavango Delta and boat ride on River Gomoti were thoroughly enjoyable. So also was our tour of Francistown; the hike up the summit of Nyangabwe Hill; and the wonderful Tswana traditional dinner at Lucy Hinchliffe’s Kuminda Farm. And travelling by bus with common folk from Gaborone to Francistown and from Francistown to Maun (a distance of more than 900 kilometres) vastly improved our understanding of settlement patterns in Botswana.

We will discuss Ethiopia’s spellbinding attractions in addressing the three big take-aways of the trip, starting with the segregated nature of Cape Town and Namibia.

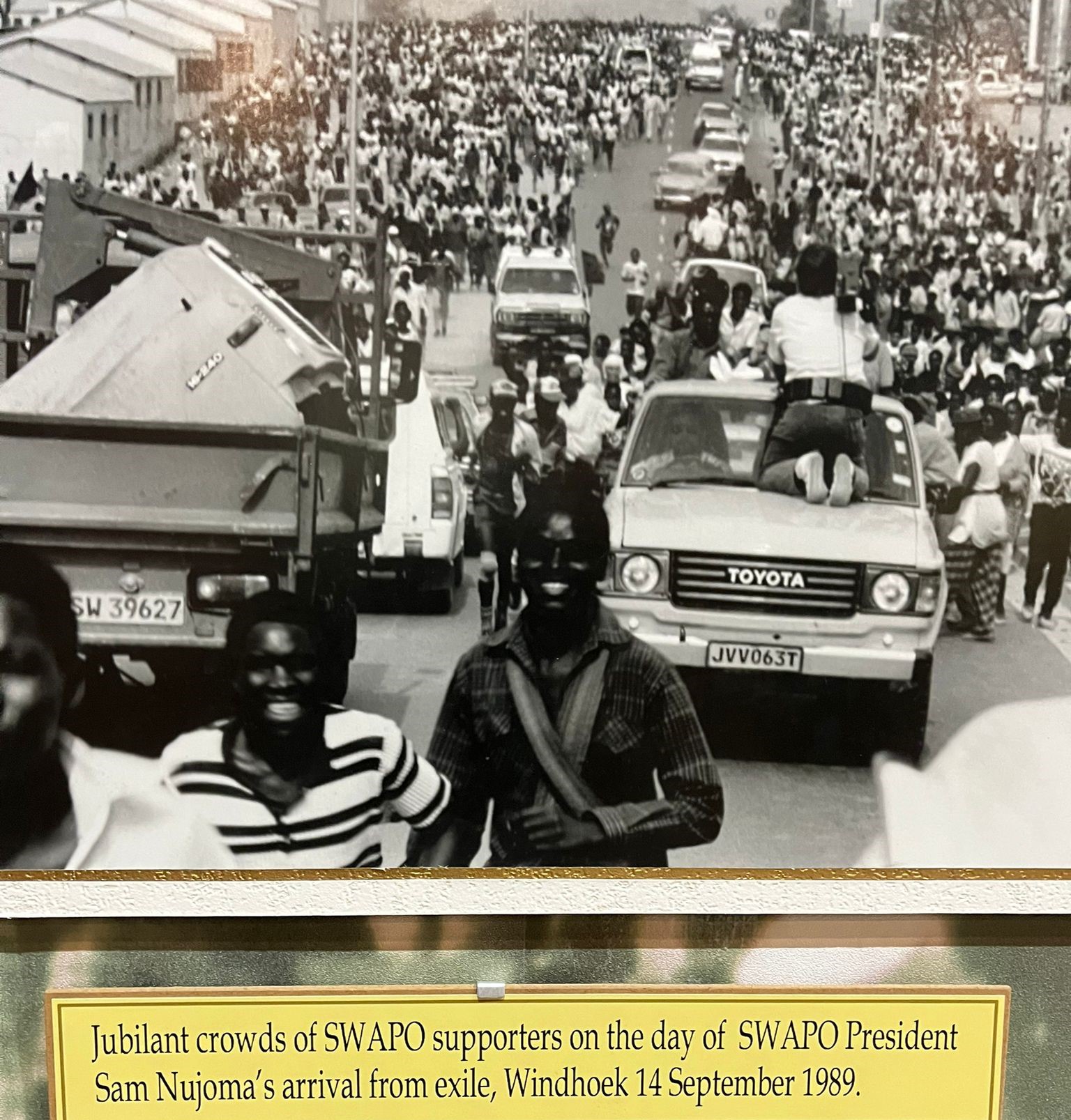

The spectacle of women combatants in the national liberation struggle in Namibia

*The obscene legacy of racial segregation in Namibia and Western Cape*

Travelling around the four countries vividly conveyed the differential impacts of Western colonialisation on African societies. The most racially abused, distorted and dominated of the four places were Namibia and Cape Town.

The dehumanising legacy of apartheid and white supremacy is still very visible in Namibia and Cape Town. Nothing captures this reality more than the highly segregated patterns of living by whites and the majority of black people in urban areas.

Cape Town and Stellenbosch in South Africa, and Swakopmund and Walvis Bay in Namibia have remained privileged white outposts surrounded by sprawling shanty towns with incredibly abhorrent levels of living for the majority of urban black people.

Liberation from the devastating effects of white racism is still a distant dream in the townships. Some black people have broken through the racial barriers, but the vast majority are still trapped in abject poverty and unlivable settlements.

At Hout Bay, a rich white suburb in the Western Cape, we saw unemployed young black men and women at the traffic lights of roundabouts waiting to be picked up by white people from rich homes for daily domestic chores.

Big, immaculate white-owned houses in leafy neighbourhoods had dreamland swimming pools and high electric fences. The contrast with the more than 400 high density townships with tin shacks and poor sanitation, many of which we passed through, was mind boggling, depressing and obscene.

We couldn’t believe that such dehumanising places still existed and seemed to be expanding even after 30 years of the dismantling of the formal institutions of apartheid.

Khaylitsha, a township of about two million black people, sandwiched between the overwhelmingly white and opulent Stellenbosch and Cape Town, is utterly disgraceful. Blue makeshift plastic structures serve as public toilets in parts of the township. We observed a similar pattern of blighted black lives in Katutura, Mondesa, and Kuisebmond—the main townships of Windhoek, Walvis Bay and Swakopmund.

Data from Statistics South Africa indicate that South Africa has made great strides in the provision of electricity, water and sanitation to the majority of its black population. However, it was deeply depressing to see a large number of people living terribly deprived lives in overcrowded townships and their historical oppressors basking in unimaginable affluence.

An indicator of a more comprehensive approach to development in this scene from Cape Town

The racial character of some of the white suburban towns, such as Llandudno, has been protected by rules that make it difficult or impossible for commercial activities to develop or buses to ply the areas. A town like Cape Ajulas, which is the southernmost tip of Africa, and where the Atlantic and Indian Oceans meet, should be an attractive tourism site. However, it is a difficult place to visit because of the lack of a bus service to the town. The front desk staff at our hotel informed us that we would have to hire a private car, which would have cost us between USD300-400, for a distance of about 223 kilometres. 86% of the 40,000 residents of the town are white.

We observed that the further we moved away from the city, the more homogeneously white Cape Town’s beaches became. The most racially heterogeneous and widely patronised beach by Africans was Camps Bay Beach. The magnificent Water Front was also highly heterogeneous even though it was dominated by whites.

However, in both of these places, the heterogeneity we observed was a salad bowl—not a melting pot.

The ‘races’ moved, and even interacted, within the same spaces, but each ‘racial group’ maintained its distinct character: blacks largely moved with blacks, whites moved with whites, coloureds moved with coloureds, and Indians moved with Indians.

Even though this obscenely cruel and dehumanizing monstrosity that was crafted by Afrikaaners was well known to us, we were still flabbergasted having to confront it every day in the urban landscapes of Cape Town, Swakopmund and Walvis Bay.

*Botswana’s transformation from a beggar nation to an upper-middle-income country in a timescale of 39 years*

As a student of development, I have, over a number of years, followed discussions on Botswana’s rapid transformation from one of the world’s poorest countries to an upper-middle income country within a timescale of 39 years. I even coordinated three projects for the UN Research Institute for Social Development in the 2000s that involved inputs from Batswana scholars. I visited the country in 2006 for one of the projects—on poverty reduction and policy regimes—which involved a team of six researchers.

However, this was the first time that I was able to move extensively around the country to see what it has achieved since its poor or humble beginnings in 1966.

My reference point was its GDP per capita, which stood at USD7,249 in 2023. This was a far cry from the miserly USD90 recorded as its GDP per capita when it attained independence in 1966. It is now on average wealthier than South Africa (which has a GDP per capita of USD6,253) and Namibia (USD4,473). All three countries are classified as upper-middle-income by the World Bank.

As I told a few friends in personal WhatsApp exchanges, the differences in levels of living and infrastructural development between Botswana and countries classified as low income (which have per capita incomes of less than USD1,145), such as Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia are like day and night. Botswana outperforms them in all major economic, social and infrastructural development indicators. And the differences captured in official statistics clearly passed the eye test during our tour.

We covered more than 3,000 kilometres in Namibia and Botswana, using public buses and taxis, and saw not just the cities, but medium and small towns as well as villages.

Remarkably, Botswana, Namibia and South Africa were comparable in road infrastructure and basic services, such as water and electricity, but Namibia lags behind in sanitation, especially outside of the big cities and towns. And all three countries are well connected with the Point of Sale (POS) Western payments system, making it easier to travel around without cash. Levels of literacy and access to health care are also very high in all three countries.

However, Botswana vastly outperforms Namibia and South Africa in one important area of development: housing. It was really refreshing to see that the tin shacks that defined the housing experiences of urban black people in South Africa and Namibia were completely absent in Botswana. In other words, we didn’t see a single tin shack in Botswana. Even the smallest house is made of concrete. Driving around rural Namibia and rural Botswana vividly illustrated to us why Botswana is ranked vastly higher than Namibia in income per capita. Rural Batswana live in far better houses than rural Namibians.

One report indicates that 85% of Batswana households live in good quality houses. Importantly, 87% of the walls, 94% of the roofs and 92.7% of the floors of Batswana houses are of good quality.

There is, of course, an urban-rural divide in house quality. More than 90 percent of the houses in urban areas are of good quality. However, even though the quality of houses dips in rural areas, almost 70 percent of them are still categorised as good quality.

Taking care of a more secure future by guaranteeing quality education of today’s children

When I was doing my doctoral research at the LSE on the international role of the pound sterling and decolonisation in Africa in the 1970s, I never imagined that Botswana would attain its current level of development. Records that I consulted at the time showed that the UK government saw Botswana as a drain on the UK treasury and considered handing it over to South Africa.

Botswana’s discovery of diamonds in the 1970s was a game changer, as it fuelled a long period of economic growth. Largely uninterrupted high levels of economic growth over 39 years; sound macroeconomic management; creation of sovereign wealth funds to cushion the effects of diamond price fluctuations, stabilise the evonomy, and save money for future generations; and massive investments in infrastructure, health, and education were the key to the country’s remarkable transformation. It became an upper-middle-income country in 2005.

Botswana avoided the resource course of bad governance, fantastical levels of corruption and overvalued currencies associated with mineral-rich countries. Tourism and agriculture, especially cattle rearing and meat production, still flourish alongside the diamond economy.

Remarkably, this transformation was midwifed through democratic politics. A culture of free, fair, and competitive elections is deeply entrenched in the country. Because of the numerical dominance of the Tswana in Botswana’s ethnic structure, ethnic politics is not divisive or virulent. The votes of the Tswana are not concentrated in one party. They are healthily distributed widely among the various political parties. This makes it possible for individuals from smaller ethnic groups, such as the Kalanga, to play active roles in parties led by Tswana.

When the ruling party that had governed the country for 58 years since independence, the Botswana Democratic Party, was kicked out of office in October this year, just four days before we arrived in the country, it was a massive, nation-wide swing or rejection of the party.

Botswana’s biggest challenge today is how to deal with the decline in diamond prices and revenues, the collapse of economic growth, and the failure to transform its long-run growth into a diversified economy that can generate jobs for its young population. It shares with South Africa and Namibia very high levels of unemployment, which were a key factor for the defeat of the ruling party in the recent elections.

*Ethiopia’s rich cultural heritage and unrivalled sense of independence*

We had wanted to explore Ethiopia much more than we did, but the worsening security situation limited our activities largely to Addis. This turned out to be an advantage as it allowed us to extensively explore the capital.

Addis had two big impressions on us: its projection of Ethiopia’s rich cultural heritage and deep sense of nationalism and independence. The proud and rich history of the country is told in many amazingly well maintained museums in the city.

Two strands of the country’s cultural heritage stood out. The first was Ethiopia’s long historical connection with Christianity through the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, which was a branch of the Egyptian Orthodox Church in Alexandria until 1959. This makes Ethiopia the only country in Sub-Saharan Africa that did not experience Christianity through European colonialisation.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church dates back to the christianisation of the Aksum Kingdom in northern Ethiopia in the fourth century. The history of this church is told in a number of museums and palaces, such as Emperor Menelik the Second’s Palace at Mount Entoto, which contains St. Mary’s Church and the oldest church building in Ethiopia; Haile Selasie’s Palace, which has been converted into a musuem and office of the Institute of Ethiopian Studies at the University of Addis Ababa; and the headquarters of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, where Haile Selasie was buried, which was under renovation when we visited.

We were fortunate to have Tariku, a practicising orthodox Christian, as our guide. We learned a great deal about the Ethiopian Orthodox religion, its Christology and how it differs from Catholicism, its main holidays,its connection with Alexandria, and its culture of fasting. Ethiopian orthodox Christians don’t eat meat on Wednesdays and Fridays. Tariku devotedly observed this practice during our travels.

The second strand of Ethiopia’s rich cultural heritage was the monarchy, which was strongly connected with the Orthodox Church. Indeed, the current headquarters of the church was built by Emperor Haile Selasie. And Emperor Menelik II was also associated with the building of the St Mary’s Church at Mount Entoto.

Ethiopia’s imperial grandeur, depicting splendid handwoven gowns, uniforms, intricately designed crowns, shields, spears, drums, coins, beds, household utensils, and much more is extraordinarily captured in many museums. The most outstanding of these museums was the 20-hectare Unity Park. Six emperors and heads of state lived in those fabulous palace grounds before they were converted to Unity Park. Unity Park was a museum of astonishing sophistication and grandeur.

Author and wife paying homage to some national liberation stars which serves in the absence of pictures of the battle of Adwa where Africans gave aspiring colonialists the beating of their life

The Adwa Victory Memorial or museum completed the story of Ethiopia’s rich history. Adwa symbolised Ethiopia’s deep sense of independence and pride. This vast and imposing museum celebrates the country’s landmark victory over Italy in 1896–the only time that a European power was defeated by an African country during the period of Western colonisation of Africa. The Adwa victory has been linked to the famous Pan-African Congresses, the anti-colonial struggles of the 20th century, and the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity in 1963.

Travelling around Addis and its environs left us with a vivid impression that Africans were in charge of their own destiny in Ethiopia. Of the four countries we visited, Ethiopia is the only one where African entrepreneurship was visibly high. Even Botswana that has done exceedingly well economically does not measure up with what we saw in Ethiopia in the field of entrepreneurship. The Batswana state has a huge stake in the diamond and cattle industry, but local entrepreneurship outside of agriculture and cattle rearing is not well developed.

Addis is going through a major infrastructural transformation. The central business district is huge and impressive. However, the country still lags behind the three Southern African countries we visited in terms of development, and poverty is endemic. But the effects of the high levels of economic growth of 9% between 2000 and 2017 are clearly visible. With a GDP per capita of USD1,020, it is projected by the World Bank to become a lower-middle-income country by 2025.

Like in Namibia and Botswana, Ethiopia still faces huge challenges in diversifying its economy and expanding its manufacturing sector. On our way to Bishoftu, we passed through its huge, widely reported industrial park, the flagship project that was supposed to spearhead manufacturing development. Much of the land looked idle. We learned that the Covid crisis and insecurity have held back the establishment of factories at the park.

Ethiopia will also have to reform its authoritarian politics and tackle its highly divisive ethnic relations to realise its full potential. Addis is surrounded by Oromia, the country’s largest ethnic group, some of whose leaders are waging a war for an independent Oromia state. Travelling far out of Addis has become almost impossible. The farthest we went out of Addis was Bishoftu, about 60 kilometers away, to enjoy the beautiful lakeside resort of Kuriftu. Tension is also high in the north, where the Tigray are also fighting for autonomy.

This ends our travelogue. We thank you for following our updates.

Dr Bangura wrote from Nyon, Switzerland