The debate on whether Nigeria is a failed state or not continues in the Western world. In a Foreign Affairs piece on May 5th, 2021, a Nigerian and a UK based scholar took the position that Nigeria isn’t a failed state. They gave their reasons. Now, another pair, connected to the spaces of articulation of the American State are are saying in this piece below that Nigeria is actually a failed state. Both Foreign Affairs and Foreign Policy are US based journals. The debate brings back the poser as to whether there can be failed states without successful states and if the successful states can be free of complicity in state failure. Read on!

The first step to restoring stability and security is recognizing that the government has lost control.

Nigeria has long teetered on the precipice of failure. But now, unable to keep its citizens safe and secure, Nigeria has become a fully failed state of critical geopolitical concern. Its failure matters because the peace and prosperity of Africa and preventing the spread of disorder and militancy around the globe depend on a stronger Nigeria.

Its economy is usually estimated to be Africa’s largest or second largest, after South Africa. Long West Africa’s hegemon, Nigeria played a positive role in promoting African peace and security. With state failure, it can no longer sustain that vocation, and no replacement is in sight. Its security challenges are already destabilizing the West African region in the face of resurgent jihadism, making the battles of the Sahel that much more difficult to contain. And spillover from Nigeria’s failures ultimately affect the security of Europe and the United States.

This designation of repeated failure is not a knee-jerk, casual labeling using emotive and pejorative words. Instead, it is a designation informed by a body of political theory developed at the turn of this century and elaborated upon, case by case, ever since. Indeed, thoughtful Nigerians over the past decade have debated, often fervently, whether their state has failed. Increasingly, their consensus is that it has.

There are four kinds of nations: the strong, the weak, the failed, and the collapsed. According to previously published research estimates, of the 193 members of the United Nations, 60 or 70 are strong—the nations that rank highest in the listings of Freedom House, the human rights reports of the U. S. State Department, the anticorruption perception indices of Transparency International, and so on. There are three places that should be considered collapsed: Somalia, South Sudan, and Yemen.

Eighty or 90 U.N. members are weak. Weakness consists of providing many, but not all, of essential public goods, the most important of which are security and safety. If citizens are not secure from harm within national borders, governments cannot deliver good governance (the essential services that citizens expect) to their constituents.

Possibly a dozen or so states are failed, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, and Myanmar. Each lacks security, is unsafe, has weak rules of law, is corrupt, limits political participation and voice, discriminates within its borders against various classes and kinds of citizens, and provides educational and medical services sparingly.

Most of all, failed states are violent. All failed states harbor some form of violent internal strife, such as civil war or insurgency. Nigeria now confronts six or more internal insurrections and the inability of the Nigerian state to provide peace and stability to its people has tipped a hitherto very weak state into failure.

According to political theory, the government’s inability to thwart the Boko Haram insurgency is enough to diagnose Nigeria as a failed state. But there are many more symptoms.

At a bare minimum, citizens expect their states to keep them secure from external attack and to keep them safe within their borders. The bargain that subjects long ago made with their sovereigns was being kept from harm in exchange for allegiance and taxation. When that quid pro quo breaks down, a state loses its coherence, its social fabric disintegrates, and warring factions subvert the social contract that should provide the fundamental foundation of the state. Nigeria now appears to have reached the point of no return.

Indeed, few parts of Nigeria are today fully safe. In 2020 and so far in 2021, according to weekly tracking reports by the Council on Foreign Relations, about 1,400 Nigerians have lost their lives to Islamist insurgents in northeastern Borno state and neighboring areas.

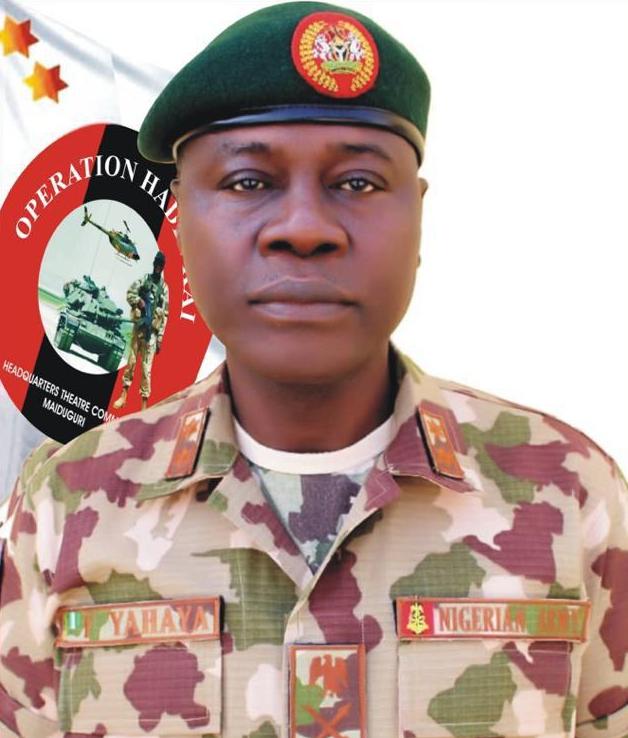

Boko Haram, a fundamentalist-inspired militia of possibly 5,000 attackers, also raids neighboring Chad and northern Cameroon, and is believed to shelter in the Sambisa forest along Borno’s mountainous border with Cameroon. Exactly why a Nigerian Armed Forces of 300,000 troops and a $2 billion budget has failed to extirpate Boko Haram is not clear; corruption in the military is allegedly a major factor, as well as inconsistent leadership from officers and politicians. (And, like Afghanistan’s Taliban, Boko Haram seems to have some limited local support.)

According to political theory, the government’s inability to thwart the Boko Haram insurgency is enough to diagnose Nigeria as a failed state. But there are many more symptoms.

In the western areas of the Muslim north, particularly in the large and populous Kaduna, Katsina, and Yobe states, gangs of kidnappers have preyed upon schoolchildren in their boarding schools. Ransom has been the motive, and payments (rarely acknowledged) have indeed been provided to return as many as 600 children to their parents after forcibly taking large groups of pupils from their dormitories, often marching them barefoot to distant holding pens. Federal and state security forces seem so far to have been mostly perfunctory in their attempts to secure schools in the northern states and generally unable to protect their trusting citizens.

In these same northern states, and farther south in Nigeria’s Middle Belt, Muslim Fulani herders have for several years been clashing with settled agriculturalists over access to land and water. These contests are often violent and recurrent. Neither central nor state government security brigades have secured these areas.

In the south, where Fulani incursions now also worry settled farmers, Igbo-speaking insurgents have recently resurrected the Biafran secessionist movement that sought to take that southeastern region out of Nigeria in 1967-1970. Now the Indigenous People of Biafra, a separatist movement that reflects and facilitates popular discontent, is gaining support among the Igbo, Nigeria’s third-largest language group.

In foreign capitals, an honest acknowledgment that Nigeria has failed ought to generate further assistance from the African Union and foreign donors

Nearby, there remains festering discontent against the central government among the Ijaw and Ogoni peoples of the Niger Delta, who feel deprived of the oil wealth that comes from their waters but largely ends up in the hands of political and economic elites connected to the government of President Muhammadu Buhari and its predecessors. In 2006, the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta began to assert the rights and claims of its followers, but it is now less formidable as an insurgent force. Nevertheless, bombings, assassinations, and kidnappings in the Delta region, including the major city of Port Harcourt, continue, further destabilizing the region.

Offshore, the Gulf of Guinea is now the most dangerous shipping zone in the world; nowhere on Earth do pirates strike more often. More than 130 sailors were taken hostage last year by pirates operating from strongholds in the Niger Delta, and the Nigerian Navy has seemed powerless to secure its waters.

Corruption, always a problem in Nigeria, has remained endemic. Buhari’s administration came to power in 2015 and won reelection in 2019 with promises to clean up corruption. But Nigeria is as corrupt at every jurisdictional level as it has been for decades, which greatly hinders the continuing struggle against insecurity. Transparency International’s latest Corruption Perceptions Index ranks Nigeria toward the bottom—at 149th of 180 countries.

Calling out failure for what it is may induce the government of Nigeria itself to take notice and to exert itself to keep constituents safe, reduce the several civil conflicts that plague many parts of the nation, prevent a plethora of kidnappings of schoolchildren, eliminate piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, and contain violent contests between herders and farmers.

In foreign capitals, an honest acknowledgment that Nigeria has failed ought to generate further assistance from the African Union and foreign donors, such as the United States and European Union. In the recent past, U.S. and British surveillance flights have helped target insurgents and locate kidnappers. If the Nigerian government asks for renewed help and can use it effectively, some of the results of failure can be ameliorated. But acknowledging state failure will help and could marshal military as well as policing support focused in the future on Boko Haram and the country’s other zones of conflict.

Only a new determination by Buhari and the political class to restore security and a sense of safety to Nigeria’s citizens can prevent the nation from spiraling further into failure and despair. The kinds of committed leadership that have been lacking in Nigeria for at least a decade will be necessary, plus renewed efforts to reduce the fraud, graft, and embezzlement that are fundamental to Nigeria’s weaknesses as a state and that are compelling contributors to its failure.

Only Nigeria can save itself, but doing so takes the kind of political will that has so far been wanting.

Robert I. Rotberg is the founding director of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Program on Intrastate Conflict and president emeritus of the World Peace Foundation. His most recent books are Things Come Together: Africans Achieving Greatness in the Twenty-first Century and Anticorruption. He edited When States Fail: Causes and Consequences and Crafting the New Nigeria.

John Campbell is the Ralph Bunche senior fellow for Africa policy research at the Council on Foreign Relations. A career foreign service officer, he served as ambassador to Nigeria from 2004 to 2007. His most recent book is Nigeria and the Nation-State: Rethinking Diplomacy With the Postcolonial World.