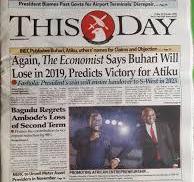

It is no mystification to say that The Economist is no ordinary weekly, more so it’s Intelligence Unit which is nevertheless involved in selling mediated information. With its fortune telling in favour of Atiku Abubakar, the presidential candidate of the People’s Democratic Party, (PDP) in the February 16th, 2019 poll in Nigeria, the contest has now entered its most fierce phase, with the global dimension of the domestic fragmentation now clearly drawn out. Of course, The Economist as well as the Economist Intelligence Unit, (EIU) could get it wrong. It is not clear if it can get the sort of discursive data that determine election outcome in non-industrial societies such as Nigeria. But that’s not the sort of fate it would wish to befall its prediction. Certainly not its prediction on Nigeria or South Africa and this is thus the kind of situation in which Stuart Hall’s claim about discourse is extremely referential. Hall says discourse is important because the promoters of any particular discourse are almost always those who are powerful enough to make the reality they invoke to happen. Those who have eyes had, therefore, better begin to see. The Economist/EIU cannot be understood in and of itself but in terms of how and for what it speaks. This prediction is a language game circulating power. The meaning is that those who cannot see beyond what meets the eye such as the Kano crowd could be heading for a heart attack on February 17th, a day after the voting.

Both Nigerian newspapers were reflecting the changing positions of The Economist.

That is where the problem lies. Unlike 2015, the incumbent and his ideologues and followers think it has performed and ought to win or has won the election already. Even as easily as they manifest jitters, more than 90% of them, spanning the top and the bottom, think like that. Its intellectuals also do. In that circumstance, a very tight race embodies the very conditions for violent conflict. Additionally, these guys think Atiku Abubakar and the PDP are nation wreckers, a very corrupt, Machiavellian pack. On the other hand, the Atiku Abubakar ensemble of cadres and supporters think the Buhari counterpart are nothing but a pack of old fashioned, hyperactive hypocrites with the mindset of school prefects unfit for a modern society. Both camps think of each other to be unworthy of power. Perfect enemy images that can provoke and sustain a long drawn out conflict because each side claims the other is a threat to state survival. It has been said many times that Nigeria would crash should Buhari win a Second term just as Buharites say that unless they kill corruption, corruption will kill the country! So, in the end, each camp markets itself as the only guarantor of the Nigerian State. Being his last shot at presidential power, Atiku Abubakar might not be as restraining of his supporters as presently imagined in such a situation and the fear is thus not only of a volatile Buhari crowd on cue to enact a bloody romance between the dog and the baboon in the event of the ‘wrong’ winner.

It is not clear whether The Economist/EIU can see all these. What is clear is how some people are already doing so. Prof Ibrahim Gambari, for example! Gambari is suggesting the intervention of elder statesmen in the country as a way of getting out of the verbal warfare over the suspension of Justice Walter Onnoghen as the Chief Justice of the Federation. Ordinarily, that is the best way out of creases in a country of Nigeria’s diversity. He is talking of the imperative as well as the possibility of producing peace through a dialogic engagement among symbolic referents in the national community. But, in spite of the dexterity in managing the national question that the power elite in Nigeria is credited with, the country itself operates in the very opposite direction.

One, having been driven by the ambition of individual politicians without the ideas of how to build a country, Nigeria is now almost an impossible polity – dysfunctional, chaotic, lawless and uncaring (or half of the population would not be living below the poverty line). As such it is both afflicted by conflict management failure as well as endemic catastrophe, apologies to Eghosa Osaghae, the University of Ibadan scholar of comparative politics whose 1994 journal article came with that memorable title “The persistence of conflict in Africa: Management failure or endemic catastrophe?”

Prof Ibrahim Gambari

Second, speaking in 2010 as Chairman of the 50th birthday ceremony labour elements held for Comrade John Odah in Abuja, Ambassador Babagana Kingibe said, amongst other things, that everything the late Festus Iyayi had said as the Keynote speaker could have been said differently in a less alienating language. In other words, he did not quite disagree with Iyayi’s contention that Nigeria was at risk from a ruling class that was driving the country to perdition but would not soft pedal. Instead, he singled out Comrade John Odah whom he said was a model of an effective trade unionist because he is the “one who didn’t shout, who eschews cliches and didn’t use ideologically tainted words “that mean nothing”. “John as a negotiator presents you little windows so that you can escape an approach which creates opportunity for dialogue. With John, there is no confrontation, no bravura. I hope you would evolve common grounds which will recognize that something which is wrong is wrong, which is false is false”. What one of the most informed members of the elite was communicating is that within that class, the substance of what its Others says could suffer appreciation because of the language in which it is said. It is a significant communication because he was echoing a similar sentiment that led NPN mandarins to discontinue attending the ABU, Zaria seminars series because they argued that Bala Usman and ‘his boys’ were disrespectful or abusive. It was both surprising and interesting that, in his own case, Kingibe sat through the occasion, absorbing the series of stinging reprimands being unleashed on the Nigerian establishment by veterans of the labour struggle in Nigeria.

Third, both the radicals and the non-radicals are so intimidated by categories as ethnicity, religion and region that they have shut them out in favour of unity or national cohesion. It has been such that when the national question forced its way back into the agenda of politics, Nigeria was least prepared for it. Nobody has worked towards a repertoire of the defining stereotypes of the ethnic groups in Nigeria with the hope of harmonizing them into a national culture, for example. The stereotypes, ethnic enemy images and references are there in the spaces of the everyday – eating houses, beer parlours and in the media but there is no consolidated engagement with them because the radicals, in particular, have been inducted into avoidance as its conflict handling model in dealing with ethnicity, religion and region. Yet, majority of the people framed and continue to frame oppression and inequality in ethno-religious terms. Instead of coming to grip with that as a gap in our knowledge of nation building, it was treated as false consciousness. The liberals are less guilty of this than the radicals in this regard. At least they came up with a model such as zoning. It has made its own contribution to stability, warts and all, putting radicals in a dilemma: they can neither defend nor attack it even as they never considered that as anything but reactionary.

Fourth, the power elite in Nigeria has this habit of commencing its conversation on the nation with the most divisive issues. Instead of deliberately starting with the areas of consensus and then walk up to the more difficult issues, they do it the other way round, quickly clash and block the possibility of much progress. It is shocking the nation has not broken up although we don’t know enough of the balance between the internal and external sources of the initiatives that have kept it intact. What is known is the constant breakdown of ‘consensus’, to the extent that there is any at all.

That there is almost none is what appears to fire Prof. Ibrahim Gambari, the retired diplomat and former Foreign Affairs Minister to note the absence of statesmen in terms of producing understanding across the board with a view to crisis prevention. But where are the elders that can produce peace in the current situation, more so with the phase of discursive warfare The EIU has added?

All else are still combatants except Gowon, still ‘Going On With One Nigeria’, behind the scenes and in prayers

Another pair of influencers

It bears repeating that Nigeria has no Mandela, whose voice would ring through the national space, bringing everyone to attention, including those who might not agree with him. In Nigeria, there are several living ex- Heads of State, the only few who enjoy instant name and voice recognition across the country. However, not only are almost all of them still in partisan politics, it is their fragmentation and score-settling politics that is at issue in this election. That leaves only General Yakubu Gowon in terms of that level of moral authority, especially from his ‘No victor, no vanquished’ phrase. He could stave off impeachment in 2002 but have time and space been standing still? There is General Abdulsalami Abubakar, well honed in peacemaking but is 2015 2019? General TY Danjuma is angry but he certainly would not want a breakdown of law and order on a conscience disturbing scale. Dr. Goodluck Jonathan does have a national constituency The Sultan of Sokoto; the Obi of Onitsha, the Ooni of Ife and the Catholic Archbishop of Abuja have not made statements that identify them as manifest defenders of one exclusionary camp or the other. There must be many more that a peace maker’s mission can compile and add to these more ready names. It could still be morning yet on creation day for Nigeria!