Those who might not have expected anything of headline making stuff from a traditional ruler such as the Och’Idoma of Idoma must have been surprised at the message from the traditional head... Read more

Come February 12th, 2025, a symposium will take place in Abuja, Nigeria. The symposium whose topic is “Role of Philanthropy in Strengthening Democracy in Africa” is to mark the 6... Read more

It is not impossible but very unlikely that these books form part of the reading list anymore across Nigerian universities. But they were the books without which the First Degree in the Huma... Read more

The journalistic infatuation with indulging big languages, cultural groups and centres of power and authority would make it difficult for some readers to come to terms with any platform payi... Read more

A Round-table on “Curbing Hate Speech in Nigeria’s Public Space” at Veritas University, Abuja Wednesday turned out to be a dramatic, surprise-filled and stormier one than any other in the pa... Read more

It is the Nigerian equivalent of the overarching question in the aftermath of the seductive thesis of ‘CNN Effect’ which argues that media reporting of humanitarian crises shortly before and immediately after the end of the Cold War were such that constrained powerful states to hasten their intervention and restore peace in far flung corners of the world. British journalist, Nik Gowing problematised this claim, went to work researching it. He came out with a devastating conclusion that almost dismissed ‘CNN Effect’. The way the media report (humanitarian) crises only pushes a government to act if the government itself did not already have a position was what his evidence told him. Where that is not the case, said Gowing’s report to the Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict, no amount of front page stories or editorials would move the hard headed realists in Pentagon or the EU bureaucrats in Brussels to move troops to any and every flash points. His research report was in 1997.

In 2007, there was a powerful support for Gowing’s position when General Romeo Dallaire, the Canadian Commander of the UN troops in Rwanda wrote in the Introduction to a book on the Genocide by another British journalist that because all the great powers had decided against sending troops to Rwanda, no media reporting or misreporting changed anything. Since then, only journalists who have not acquainted themselves with the literature go about endlessly hawking the idea of the power of the media to set agenda without connecting such claims to the power context within which such could happen. It is only now that the Nigerian variant of that question is being posed. That is understandable in the sense that it was only with Boko Haram insurgency that Nigeria came face to face with the question of how the media could play its role in transforming the violent extremist convictions that drive the insurgent impulse. In this case, the issue was whether the media, on balance, has been amplifying the insurgency and insurgents or been hindering them, consciously and/or professionally?

In 2007, there was a powerful support for Gowing’s position when General Romeo Dallaire, the Canadian Commander of the UN troops in Rwanda wrote in the Introduction to a book on the Genocide by another British journalist that because all the great powers had decided against sending troops to Rwanda, no media reporting or misreporting changed anything. Since then, only journalists who have not acquainted themselves with the literature go about endlessly hawking the idea of the power of the media to set agenda without connecting such claims to the power context within which such could happen. It is only now that the Nigerian variant of that question is being posed. That is understandable in the sense that it was only with Boko Haram insurgency that Nigeria came face to face with the question of how the media could play its role in transforming the violent extremist convictions that drive the insurgent impulse. In this case, the issue was whether the media, on balance, has been amplifying the insurgency and insurgents or been hindering them, consciously and/or professionally?

It was not a secret session but an understandably discreet, reflective exercise within the context of transforming violent extremism and inclusive peace by the Nigeria Office of one of the conflict transformation and peace building INGOs. But, instead of a single journalist researching and writing a report on the question, the NGO gathered selected journalists across Nigeria to turn on themselves and see how well or otherwise they have fared and how far the media still have left to go. So, what did they find in the self-reporting?

From universities to think tanks, government departments and sundry actors, some of the world’s best brains are still wrestling with the slippery concept of Terrorism. Up to a point, the United States alone had four different definitions. When is an act terrorist? Journalists, media advisers and many government officials hardly distinguish between a guerrilla tactic and a terrorist act. Experts have been worried that an attack on a military check-point, for instance, ends up being reported in the media and spoken of by senior government officials as terrorism. The discussion in this reflective session showed that Nigerian journalists are no exception to this confusion. But while most global media establishments have responded to the confusion by alerting their reporters worldwide that ‘one man’s terrorist could be another man’s freedom fighter’, that appears not too well done yet at home. That is probably because Boko Haram presents no difficulty. It is a classic terrorist organisation given its explicit political goal of seeking to decenter the state and in pursuit of which it attacks groups so as to send violent messages to the Nigerian State to make a choice.

A major presentation to the session threw a number of charges on the media: taking pictures of genocide in Rwanda and passing it off as a Boko Haram atrocity; some journalists sitting down in a newsroom in Abuja or Lagos to imagine and script a story of a Boko Haram attack somewhere in the Northeast; media houses with journalists without clarity and/or research capability, among others. Set against this lead paper as it were and led by an energetic session coordinator, the discussion began. The lead question for this segment was for journalists in session to search their conscience and bring out what they think the media might be getting wrong.

Only a few out of the points raised can be taken here. One of such is the notion of the media being stuck to a reporting pattern structured by stereotypes and polarities. But there was no agreement although the ‘ayes’ were more vocal than the ‘nays’. The only one voice that did not accept that charge against the media could not win because the speaker had no empirical evidence beyond stressing that best practices in conflict reporting forbids stereotyping. Someone replied by citing a recent major television network’s story that he claimed used an ethnic identity, going ahead to say that the use of ‘Muslim fundamentalists’ or ‘Fulani herdsmen’ are good examples of stereotyping. Someone else said reporting that made no distinction between kidnapping and terrorism is an example of a stereotyping and polarising journalism which could have the effect of crediting Boko Haram with more capacity than it has.

Gen Tukur Buratai, Nigeria’s Chief of Army Staff, (COAS)

Second poser for reflection was: Is the media amplifying the claims of insurgents. Again, there was no consensus. The critics of the media on this said all the major newspapers would come out with double-decker headlines the next morning whenever Abubakar Shekau, Boko Haram leader made any claims. This, said the contributors, is journalistically bad because similar prominence is rarely accorded similar claims by the military. “When the military makes a claim about 5, 10, 20 Boko Haram leaders killed, it is not reported as Shekau’s”, another voice was heard thereto. Yet another speaker said “some media go extra mile in reporting figures of death thereby assisting the terrorists”, arguing how such is how the terrorists always feel and say they have registered what they always call a maximum damage.

The opponents then took their turn. One wanted the earlier speakers to tell him how journalists were to verify what Shekau might be claiming in a video outing. “Send someone to Sambisa?”, Sambisa being the forest Boko Haram commanders have reportedly converted into their operational base. The most vicious upper cut came from the voice that said it didn’t make journalistic sense to ignore a man the military claimed to have killed but only for him to reappear, sometimes with video showing embarrassing balance of power between his forces and the military. A tie!

A subset of this question was whether the Nigerian media reports sometimes back that Boko Haram was better armed than the Nigerian Armed Forces should ever have happened. Earlier on, someone said it should never have happened and that it was lack of patriotism. Contrary argument said all such reports were corroborated by subsequent events neither the military nor the government could even cover up. Nobody remembered to mention that this idea of insurgents being better armed than the Nigerian military was also the basis of animus against the global media coverage of MEND’s insurgency. If that had been brought in, then it might have contributed to showing how persistent this propaganda has been. But it remains propaganda because insurgents do not normally engage established militaries in conventional warfare for the sole reason that they can never win such wars. So, they rely more on improvisation. That makes it it odd to compare most insurgent groups with most national armies.

In all, the tension between the different standpoints in the reflective sessions mirrors problem with reporting terrorism. Failure to report terrorism is complicity in creating a false sense of security or of misleading the public, the results of which could be imponderable, especially for women and children. At the same time, however, reporting terrorism is inherent complicity in terrorism because terrorism is almost completely dependent on being reported. If an attack by Boko Haram is denied media coverage, it would amount to a severe de-oxygenation of the insurgency, although this has to take note that today’s terrorist organisations come along with own media pack.

The last poser was: what is the great thing the Nigerian media has been doing as far as reporting Boko Haram insurgency is concerned. For some, that must be exposing the conditions of the IDP camps, especially the lack of schools for those in the age bracket. For others, it is the concentrated focusing on rape in those camps which goes against the collective conscience of Nigerian journalists. The verdict on this seemed to be the point by the fellow who said that, in spite of everything, the Nigerian media has kept the Boko Haram story going. The inference is: imagine what Nigeria would be today if there is no coverage of the insurgency, leaving room for rumours and all manners of speculations.

It was a many sided debate from which only the thematic samplers bound to interest other stakeholders within the wider agenda of deradicalisation and peace has been highlighted. The sharp and rich repertoire of the attendees shows an active media constituency at work in the search for peace in Nigeria. It would be best if the exercise is widened in terms of participation, (the media, the military, civil society, academics, etc) and held more frequently. Then Nigeria’s engagement with transforming violent extremism would have become a most robust and rounded one.

The vicious struggle for the soul of Nigeria has, fitfully, finally and formally staggered onto the streets. Now, everyone, even the blind, can see it. If it is not in the volley of well aimed verbal missiles issuing from The Presidency on all cylinders, signifying a President Muhammadu Buhari on the move for 2019, rhetorically and otherwise, then it must be in the pot-shots on the Presidency, particularly the ones fired from Kano and Kaduna. Elder statesman, Alhaji Tanko Yakassai said the president has been successful only in noise making. As one of the very few living traditional politicians with Left background, it would not be surprising if quite a number of people did not sleep in the Villa that night. He was followed by Sheikh Abubakar Mahmud Gumi saying the president is held hostage by mad people. These are considered significant statements in terms of the pattern of ruling class constellations unfolding. But the president is soldiering on nevertheless as we shall see below.

Meanwhile, disagreement within the ruling party has spilled onto the streets. Clearly, the battlefront which has opened between the Senate President and the Executive Arm is crossing the red line of power struggle by presenting Nigeria to the world as a country whose Head of the Legislature had anything to do with armed robbery. That may be good for some people but it stretches the image of the country too thin. To undo that dent now would take years and lots of efforts because it constitutes a big flash on the screens of researchers compiling indicators of instability across the universities, think tanks and researchers, INGOs and other new such actors in global security.

There is no knowing what the outcomes would be when added to other sites of rupture such as the continued killings, (Ekiti, Benue, Edo, Plateau, Zamfara, Nasarawa and Kogi last week); rupture in the ruling party where the contest of power between the legacy components and the n-PDP has blown up to near irreconcilable dimension and, of course, the intensified search for a consensus candidate to fight out the election between the incumbent and such an entrant.

Notwithstanding the commotion, the president is soldiering on. How far it would go is not clear but, for now, the president who had nothing to say (or, was he bidding his time?) as very tragic events unfolded between January and March in particular now appears to have found his voice at last. Corruption is the organising concept of his move but he is weaving other claims in the process. Two of them are most interesting. The first one, now most forcefully and more regularly articulated, is his contention that it is those who stole public resources who are organising chaos. By that, he means that the herdsmen involved in the violence across the country are actually ‘herdsmen’ or organised players by the people he is pointing fingers at. Interestingly, this was not his initial theory. The sequence of his intervention has been silence, armed herdsmen, Gaddafi killers before the new theory. Perhaps, presidents also adjust theories.

Notwithstanding the commotion, the president is soldiering on. How far it would go is not clear but, for now, the president who had nothing to say (or, was he bidding his time?) as very tragic events unfolded between January and March in particular now appears to have found his voice at last. Corruption is the organising concept of his move but he is weaving other claims in the process. Two of them are most interesting. The first one, now most forcefully and more regularly articulated, is his contention that it is those who stole public resources who are organising chaos. By that, he means that the herdsmen involved in the violence across the country are actually ‘herdsmen’ or organised players by the people he is pointing fingers at. Interestingly, this was not his initial theory. The sequence of his intervention has been silence, armed herdsmen, Gaddafi killers before the new theory. Perhaps, presidents also adjust theories.

The more pointed shots were fired earlier on May 15th, 2018 at the commissioning of the new office complex of the EFCC where he declared that corruption itself overthrew him in 1985. In other words, the masterminds of that coup were on a corruption-inspired mission. Whao! Not quite a few clapped for him even as they wondered why he never began to harp on this until the onset of the campaigns.

Agreeable or not agreeable, alleged corrupt politicians across the country are being hauled into the courts, most of them ending up in jail for at least a week or so. It is a powerful way of imposing a moral censure on the individuals involved because, being arraigned for corruption diminishes anyone, whether he or she is found guilty or not guilty. It must, therefore, have been carefully planned over time to coincide with the onset of campaigns. The initial arrows in the direction of Chief Olusegun Obasanjo, one of the angry godfathers, does not appear to be flying yet. It has only fetched the president a put down by General Obasanjo. But, who knows, there might be more of such disclosures. Some snippets have started circulating in relation to General Abdulsalami Abubakar although that one has not been such a vocal member of the cohort, (the club of four or five retired Generals wielding tremendous power in the country, formally and informally) against the president’s second term bid. It could be that a friend to an enemy is an enemy. Meanwhile, not a few are sure that before long, former Vice-President Atiku Abubakar might get his own share of the anti-corruption firing. And so on and so forth!

The contradictions appear to have worked out in a manner that corruption is the issue framing the current intra-class warfare in Nigeria. Pessimists say that could be the eve of anarchy because the conflict parties appear so balanced and victory or defeat could be too costly. Optimists say the warfare is what would trigger or catapult Nigeria into a more qualitative era. Whichever line one follows, it would appear to be that, after four epochal wars against corruption in recent memory, (Murtala/Obasanjo purge in the mid 1970s; the 1983/4 arrest, detention and trial of several politicians of the Second Republic by the 1983-1985 Buhari military regime; the setting up of the EFCC in 2003 and the current phase), thesis and anti-thesis are about to build up into a synthesis although why this heightened dimension is coinciding with the eve of election is something many people are unable to explain or understand.

If it is true that on presidential agency does the future of Nigeria substantially lie, then the bigger problem remains. There is a strong belief here and there that an overwhelming opponent can defeat the incumbent hands down if the election is all a matter of first-past-the-post. But who might be that overwhelming candidate, with capacity for qualitative and nation building governance in an extraordinarily plural Nigeria?

After Ibrahim Dankwambo, the PDP governor of Gombe State, there are hardly any new names emerging yet although one of the angry godfathers might come up with a dark, dark horse. That is a strong possibility. Former Vice-President Atiku Abubakar is right in the race. He has even started appointing the henchmen of his campaign. Until the dark horse is unveiled, each of the two is gathering moss. With the frequency of movements between the Northeast and the South-south nowadays, something would appear to be clicking. Governor Dankwambo might be lucky, not being vulnerable in any way to the anti-corruption shelling because he has immunity till the end of the Buhari regime in May 29, 2019. Should he declared elected, there is no chance of anybody arresting him before midnight of May 2019 and by which time he would have become Mister President and come under a stronger immunity. That is if he has any allegations of corruption against him. Right now, none is known to the public yet. But with what more progressive doctrine of power is he ever associated with? Some people are crediting him with being the designer of the TSA mechanism when he was Accountant-General of the Federation about a decade ago? So, would his be the arrival of a technocrat in power? Is that the presidential agency Nigeria needs today? Only time will tell.

President Paul Kagame at a session of the Next Einstein Forum

Ahmed Abiy, New PM of Ethiopia also went to the ideas based Next Einstein Forum

What about the dark horse? Not much is known about him yet beyond that it is a he, not a she. The assumption is that any dark horse coming into the fray must be more formidable than anyone already in the race. Again, only time will tell. Lastly, Atiku Abubakar! He is rated to have the cash and the capacity, although the substance of the capacity has not been interrogated. He has started quoting Lee Kuan Yew, the late Prime Minister of Singapore routinely cited as the ultimate example in compacting an extra-ordinarily diverse city-state as Singapore and transforming it from a ‘Third’ to a First World. But does Atiku subscribe to Yew’s categorical discourse of social transformation in the idea of a fair as opposed to a welfare society? If he says he does, has he got how such a doctrine can be operationalised in Nigeria?

It is not impossible for a swing in choice to occur because of the multiple calculations of the powerful local, regional class and global interests and their agents in the negotiations going on here and there on 2019. Surprises could still occur just as some stars could fade, some to the dynamics at work and others as damaged brands in the anti-corruption warfare. But the strategy of damaging brands could equally be counter-productive because in an angry and acrimonious country like Nigeria of today, one person’s damaged brand could be another person’s model. And some people could be decisive in electoral outcome, even from jailhouse.

President Paul Kagame of Rwanda is a dictator. That is the sort of thing one hears more frequently about him but he is a dictator who has delivered development to a society that went through genocide. A 43 year old young man has just taken over power in Ethiopia, an ancient African State and, so far, everyone is saying that if he continues the way he is going, Ethiopia would soon be alright. What is he doing right? Educated or informed governance, manifesting in how he dashed to flashpoints of discontent and mellowed hardened hearts! By education, we do not mean PhD but political education. In Nigeria, no one ever comes to power with a self-understanding that proclaims a categorical contention about what the country should be like. All of them come to power talking about development in terms of mega and mini projects without EVER talking about an overarching framework. None! The latest is President Buhari who gave the impression that he was a statist. After three years, it is not clear if the regime has anyone there who has ever heard about the word statism. Might this country have been cursed?

It was one of the questions Intervention tried to deal with very early in its formation. The puzzle is why more conflict and violence in Nigeria at a time there are more universities and think tanks dealing with formal study of peace and peace politics? The question came about following what was clearly a massive expansion in opportunities for formal study of Peace and Conflict in Nigeria, something that was available in scattered forms in International Relations, Sociology, Psychology, Political Science, Geopolitics, Linguistics and Religious Studies.

Whereas by 2003/4, it was just the University of Ibadan programme in Peace and Conflict Studies and the same university’s Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, (CEPACS) as well as Programme on Ethnic and Federal Studies, (PEFS), there were over 20 universities, INGOs, independent think tanks and sundry centres offering one programme or another in Peace Studies by 2016. The correlation should be very clear and if that is not the case, then the question must be posed regarding what might be the intervening variable between the reality of more such centres without corresponding decrease in the quantum of violent intra and inter-group conflicts. Intervention interviewed academics and other stakeholders across the country in a two-part narrative. Each gave his or her own analyses, (See “Nigeria: Why the More Conflict Management Training, the More Conflict, Sept 5 & 6th, 2016/www.intervention.ng).

Pioneer Peace and Conflict Studies centre in the Nigerian university system

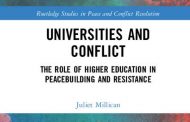

An expert from the Peace and Conflict programme at Ibadan who assessed the story post publication, however, interrogated the assumption entirely. He said the expansion under reference was overblown because many of the centres and Peace Studies programmes lacked the staff strength and the vibrancy to warrant a claim of lack of correlation between expansion in the number of study centres and decrease in (violent) conflicts. That was 2016. Now, this is 2018 and there is a book trying to account for the relationship between universities and conflict.

It is an interesting book because, for one, it has analysis from across different parts of the world – Middle East, Asia, Europe and Africa. It may not score an ‘A’ in inclusivity because there is just a chapter from (South) Africa, it is an improvement when compared to other such efforts.

Two, it basically agrees with the notion of universities as conflict managers in their own right because they are theatres of discourses of conflict, discourses which are reproductive of peace as well as conflict, depending on what the discourses are and how students of these discourses operationalise them.

The newness of this research agenda means that most readers would find the introductory chapter and Chapter Three interesting. Chapter Three is where Dr Sansom Milton of the Centre for Conflict and Humanitarian Studies at the Qatar based Doha Institute for graduate Studies reviewed the literature on universities and conflict. Those who are, however, more interested in practical issues might find the case studies chapters (4 – 11) more inviting. The case studies in university – conflict nexus cover some of the hottest conflict spaces or universities concerned with the discipline: Israel/Occupied Territory, Myanmar, Belfast, Bradford, Bosnia and Herzegovina, South Africa.

Dr Millican of the University of Brighton and editor of the new book

Edited by Dr Juliet Millican of the University of Brighton in the UK, this book contributes to closing the gap on scarcity of reading materials in a discipline still borrowing heavily from other disciplines and trying to resolve fundamental subject matter issues. Only last month, Professor John Gledhill of the University of Manchester published an article calling for an intellectual insurgency to put peace back into Peace Studies because much of the works in the discipline so far are concentrated on violence/war compared to peace and peacemaking. That could sound strange to students of Peace and Conflict in Nigeria, for example, given the strong distinction between Negative and Positive peace in Peace Studies on campuses across the country. However, Gledhill made his call based on a study he carried out last year with Jonathan Bright at the Oxford Internet Institute, Oxford University in which they described Peace Studies as a ‘divided discipline’ on the basis that “there is limited exchange between academic studies of war and research on peace”. It is possible because the quantum of Peace and Conflict Studies and publications coming out from Nigeria might be so minor of global percentage as for the two scholars to make their claim.

In all cases, this is an interesting time than any other to study and/or practice peace. This is simply because the world is still in the Interregnum: the old order is so discredited and going but the successor order is still nowhere to be seen, leaving not a void as such but an empty space upon which anyone could smartly write anything.