Francis Fukuyama Repudiates ‘End of History’ Argument?

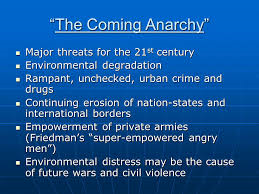

Theories do not die. They are mostly updated, the updating determined by re-interpretation of the facts on the ground. So, we are unto another global sensation when a theorist appears to be repudiating himself categorically as in this interview published today in The Washington Post (where it was published as “The man who declared the ‘end of history’ fears for democracy’s future”) in which Francis Fukuyama, scholar of post Cold War geopolitics, says his essay ‘The End of History’ which became a book later isn’t it after all. Reading the interview, one gets a sense of the confirmation of the critical discourse argument that what scholars such as Fukuyama, Robert Kaplan, author of The Coming Anarchy, among others; Samuel Huntington and his Clash of Civilisation; Thomas Barnett and his The Pentagon’s New Map and so on were doing was culturally mapping the world in the interest of the liberal world order which the United States is/was the custodian. In other words, they were scholars of statecraft. Unfortunately, the dynamics have created huge holes in their arguments which they themselves are admitting profusely. Read him out here in the interview by Ishaan Tharoor-Editor

Francis Fukuyama, an acclaimed American political philosopher, entered the global imagination at the end of the Cold War when he prophesied the “end of history” — a belief that, after the fall of communism, free-market liberal democracy had won out and would become the world’s “final form of human government.” Now, at a moment when liberal democracy seems to be in crisis across the West, Fukuyama, too, wonders about its future. “Twenty five years ago, I didn’t have a sense or a theory about how democracies can go backward,” said Fukuyama in a phone interview. “And I think they clearly can.”

Fukuyama’s initial argument (which I’ve greatly over-simplified) framed the international zeitgeist for the past two decades. Globalization was the vehicle by which liberalism would spread across the globe. The rule of law and institutions would supplant power politics and tribal divisions. Supranational bodies like the European Union seemed to embody those ideals.

Brexit and the election of President Trump last year certainly did.

But if the havoc of the Great Recession and the growing clout of authoritarian states like China and Russia hadn’t already upset the story,

Now the backlash of right-wing nationalism on both sides of the Atlantic is in full swing. This week, French far-right leader Marine Le Pen announced her candidacy for president with a scathing attack on the liberal status quo. “Our leaders chose globalization, which they wanted to be a happy thing. It turned out to be a horrible thing,” Le Pen thundered.

Fukuyama recognizes the crisis. “Globalization really does seem to produce these internal tensions within democracies that these institutions have some trouble reconciling,” he said. Combined with grievances over immigration and multiculturalism, it created room for the “demagogic populism” that catapulted Trump into the White House. That has Fukuyama deeply concerned.

Fukuyama recognizes the crisis. “Globalization really does seem to produce these internal tensions within democracies that these institutions have some trouble reconciling,” he said. Combined with grievances over immigration and multiculturalism, it created room for the “demagogic populism” that catapulted Trump into the White House. That has Fukuyama deeply concerned.

“I have honestly never encountered anyone in political life who I thought had a less suitable personality to be president,” Fukuyama said of the new president. “Trump is so thin-skinned and insecure that he takes any kind of criticism or attack personally and then hits back.”

Fukuyama, like many other observers, worries about “a slow erosion of institutions” and a weakening of democratic norms under a president who seems willing to question the legitimacy of anything that may stand in his way — whether it’s the judiciary, his political opponents or the mainstream media.

But the problem isn’t just Trump and the polarization he stokes, argues Fukuyama. What the scholar finds “most troubling” on the American political scene is the extent to which the Republican Party has gerrymandered districts and established what amounts to de facto one-party rule in parts of the country.

“If you’ve tilted the playing field in the electoral system that it doesn’t allow you to boot parties out of power, then you’ve got a real problem,” said Fukuyama. “The Republicans have been at this for quite a while already and it’s going to accelerate in these four years.”

“When democracies start turning on themselves and undermining their own legitimacy, then you’re in much more serious trouble,” he said.

International institutions don’t seem to be faring any better. Fukuyama thinks the European Union is “definitely unraveling” due to a series of overlapping mistakes. The creation of the eurozone “was a disaster” and the continued inability to develop a collective policy on immigration has deepened discontent. Moreover, said Fukuyama, “there really was never any investment in building a shared sense of European identity.”

But while the West is lurching through a period of profound uncertainty, Fukuyama calls for patience, not panic.

“We don’t know how it’s all going to play out,” he said. The tide of right-wing nationalism may ebb if the results of major elections this year go against the Le Pens of the world. Fukuyama wonders whether Trump will eventually face a backlash from within his own party, particularly if he cozies up to an autocrat like Russian President Vladimir Putin.

“The Austrian election was actually interesting,” he said, referring to a presidential vote in which a far-right candidate narrowly lost last year. “It was as if people in Europe said, ‘Well, we don’t want be like these crude Americans and elect an idiot like Donald Trump.'”

The turbulence of the moment doesn’t have to be read as a rebuttal of his original thesis. The “end of history” was always more about ideas than events. For that reason, Fukuyama’s most vehement critics over the years were not right-wing nationalists but thinkers on the left who reject the dogma of free markets. Fukuyama himself always left the door open for future uncertainty and crisis.

“Perhaps this very prospect of centuries of boredom at the end of history,” he wrote more than two decades ago, “will serve to get history started once again.”