By Abubakar Aliyu Liman (PhD)

The author, a Professor in the Department of English and Literary Studies and Dean of the Faculty of Arts @ the Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Nigeria made this Keynote Presentation at the 2nd National Conference, Department of English and Literary Studies, Faculty of Arts, Federal University of Lafia, Nasarawa State on the Theme: Language, Literature and Democratisation Process in the 21st Century” which took place November 5 the – 8th, 2023. He is reachable via GSM (2348034515966) and Email: abualiliman@gmail.com

The author

Introduction

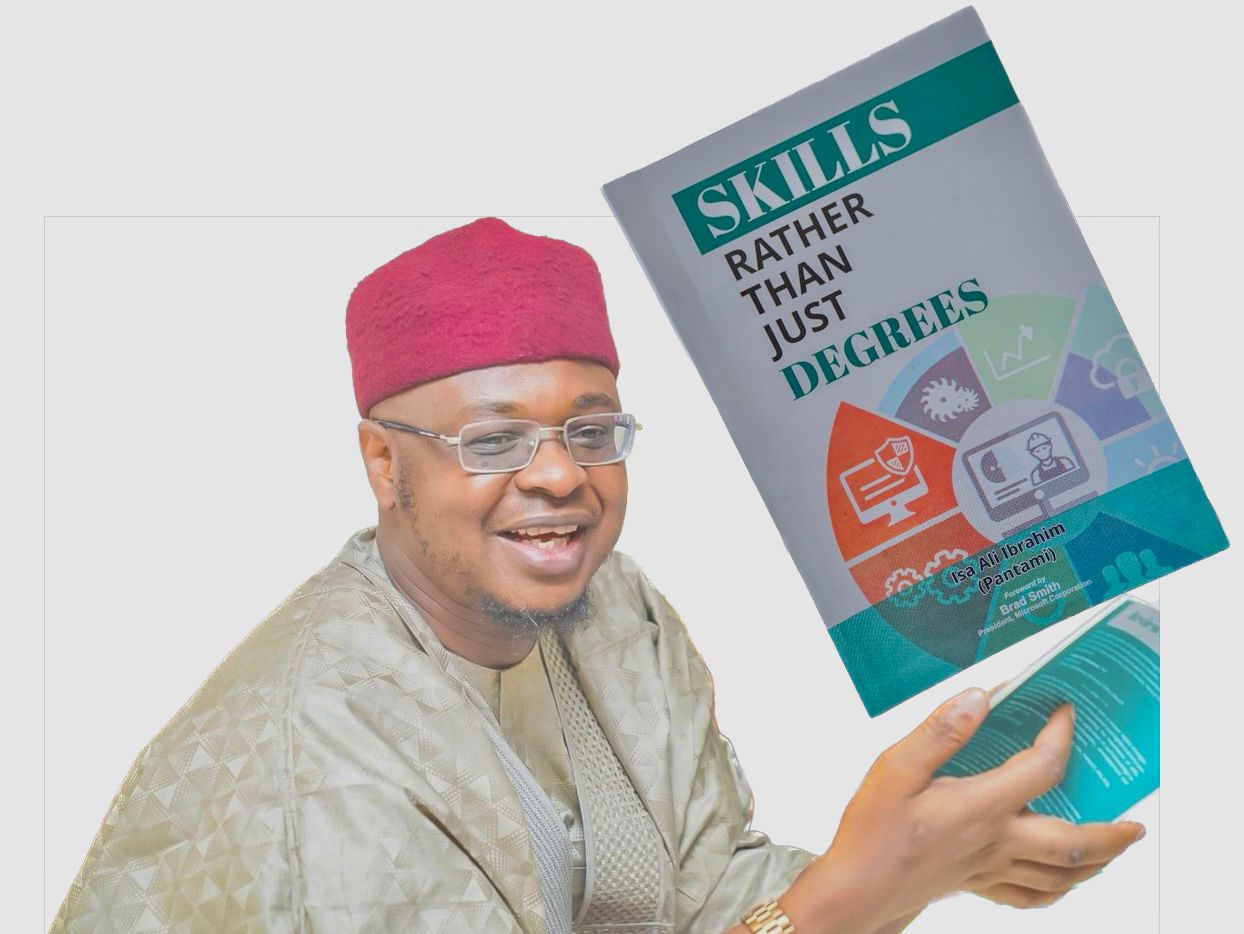

This paper foregrounds the prospects of language and literature in the 21st century in the context of unfettered debate in the social media on the need to “acquire skills rather than just degrees” as pontificated by Isa Ali Pantami, the former Minister of Communication and Digital Economy. However, little did both the protagonists and antagonists of “skills rather than just degrees” know that this issue is as old as history of philosophy. The contestation over what really constitutes knowledge is decidedly traceable to the compartmentalization, hierarchization and revaluation of knowledge in the old philosophical disquisition between the idealist and materialist philosophers of the classical and neoclassical periods, which persisted from thence right up to the 19th and 20th centuries with British Empiricists (John Locke, George Berkeley and David Hume); American Pragmatists (William James, C.S. Peirce and John Dewey); and Utilitarian philosophers (Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mills). This old debate is the precursor of the emphasis on the functionality of knowledge and technological ascendency, which the ideologues of neoliberal global order, liberal democracy and western hegemony, are frantically making attempts to shove down the throat of every modern nation. The abiding faith of the postmodern subject in the capacity of smart technologies, artificial intelligence and robotics, as well as the potential of these technologies to displace human agency in anticipation of posthuman era is only beginning to manifest its dark underbelly threatening the very survival of humanity.

In this regard, emphasis on skills rather than university degree by the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITD) in its drive to “shape the future of Nigeria’s Digital Workforce” through the ambitious three million technical talent program is just a pipedream. The effort is not germane in a situation where even the most basic education infrastructure is not available and accessible to majority of Nigerian children. Worst of all, our misguided approach to the “boundless” prospects of digital technology has been the main source of influence to our newly acquired habits of questioning the relevance of old scientific epistemic structures that comprehensively mediated the project of modernity itself. This is the context in which the relevance of language and literature pedagogy in the Nigerian university system is evaluated.

The paper argues that beyond the traditional atomistic approaches of language and literature in the institutional precincts of the academia, postmodern context requires an approach to knowledge that conflates different disciplinary backgrounds in knowledge production. On the basis of this reality, it is argued that language and literary studies, and indeed other disciplines in the humanities, should consider adopting a holistic approach to knowledge production and dissemination, which only interdisciplinary epistemic structures could offer.

Context

There is no gainsaying that Nigeria practices liberal democracy with all its attendant implications. The liberal system is for all intents and purposes implanted in Nigeria merely to deepen our dependency syndrome. It is a political package that was imposed by the forces of western imperialism without recourse to Africa’s historical and cultural peculiarities. It is part of the ideological package of laissez faire capitalism introduced to postcolonial African nations to facilitate the appropriation of Africa’s natural resources, to create market for goods and services, and to gain other geostrategic advantages by the drivers of the not so new a global system. In hindsight, the system has drastically reduced government capacity to attend to social needs and honor its obligations to the citizenry. As economic pressure bites harder, individuals and groups have expectedly become aggrieved, dispossessed, disempowered, stressed and edgy. Political analysts have consistently pierced gaping holes that revealed the presumed efficacy of the system by exposing its incapacity to tackle fundamental social problems militating against the wellbeing of the people. The analysts also see our dysfunctional democracy as a recipe for unmitigated disaster, chaos, conflicts and violence in the Nigerian society. In fact, the combination of liberal democracy and liberal economic practices has only created space for obnoxious competition and corruption over the control of scarce resources amongst variegated individuals, groups, plural identities, diverse communities and vested interests.

On the one hand, the ideals and practices of democracy have created opportunities for the poor and marginalized folks to express their grievances, and to get their voices heard even if those voices are unattended. On the other hand, democracy has massively fueled discontent as public expectations are not met as a result of corruption, avarice and self-aggrandizement through a system that only promotes the credo of the individual and the pursuit of self-interest as an article of faith. In cultural terms, liberal democracy is nurtured in a postmodern world in which normative values, ideas and beliefs that used to humanize, cohere and shape our consciousness and worldviews are increasingly coming under fire. The old values are being questioned, deconstructed and almost completely dethroned by the forces of postmodern social and political discontent. The postmodern space is accelerating the production of a new cultural paradigm, which is poised to seal the fate of our old-fashioned certainties and cultural norms. To be a little bit more explicit, the postmodern culture has thrown up unimaginable changes that have not even been anticipated at the tail end of the 20th century. The postmodern inhabitants of contemporary society are no longer confident of the old certainties produced by our traditional values, the modernity and technological bliss we aspire to achieve.

But has the disciplinary enclaves of language and literature anything to contribute to Nigeria’s bid to gain entry into the elite club of developed industrial economies based on the newfangled digital culture and economy? Recently, the question has been raised on the relevance or otherwise of disciplines in the humanities, and indeed university education as a whole. Isa Ali Pantami, has authoritatively convinced himself in a book entitled Skills Rather Than Just Degrees (2022). The take-away point in the book is that skills acquisition should be the cornerstone of Nigeria’s system of education for it to deliver on the quest for technological development and industrialization.

Pantami’s proposition is not the first of its kind here in Nigeria and elsewhere in the world. This conversation has been in the air for quite sometimes. Perhaps what many of us are not aware is, the conversation is strategically brought back to facilitate the ascendancy of global neoliberal order, which anticipates the acceptance of liberal values, high technology and knowledge economy as the new universal given of postmodern society. In such a society, therefore, it is technical skills, digital communication abilities and the mastery of computer algorithms that matter for the survival of individuals in the 21st century. To validate this claim, the netizens of our digital culture have become so vociferous in the expression of their optimism for the emergence of a world that is so dependent on technology rather than normative values and our “old-fashioned” processes of knowledge production and dissemination. Knowledge can now be acquired easily outside institutional frameworks and disciplinary structures of universities and any form of higher order learning.

The netizens of our digital age are quick at uncritically parroting a maxim coined by Alvin Toffler, the author of Future Shock (1970), who dogmatically upholds the view that the 21st century is a century of knowledge glut. In his book he alluded to a new reality, a new situation in which “the illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn”. He of course arrived at this proposition out of his anticipation of the prospects of the emergent information order and the need for dynamic approach to the skills of the future. According to Toffler, the literates of the late 20th century would become the illiterates of the future due to unimagined levels of technological intrusion in the new society in which we shall be living our lives in an age of machine learning, data science, artificial intelligence and robotics. As such the new illiterate would have to continuously “learn, unlearn, and relearn” in linearly ever-changing seam of information society and knowledge economy.

Jean Francois Lyotard in his Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (1984) has expressed similar concern. But in our hasty conclusion, it was argued that universities and indeed other conventional academic institutions elsewhere around the world would lose their capacity to minister to the needs of individuals and society in the 21st century. As the argument goes, universities would be irrelevant due to the manner in which they recircle knowledge that is no longer relevant in their research pursuits and pedagogical approaches. Never mind Terry Eagleton’s recent provocative call for the abolishment of the university. However, Eagleton was only sarcastically responding to the way in which neoliberals, corporatists and futurists questioned the “worthiness of a university” as they go about ringing bell on the need for universities to reposition themselves for the 21st century world of high technology (Eagleton, 2023). We can understand this new sensibility even from the way the National Universities Commission (NUC) is uncritically joining the bandwagon as it throws its weight behind the purveyors of skill acquisition mantra.

Here comes the regulator!

Consequently, NUC swung into action to review the Nigerian Universities Benchmark Minimum Academic Standards (BMAS), which it eventually replaced with what it calls Core Curriculum and Minimum Academic Standards for the Nigerian University System (CCMAS), a revised BMAS, which has been saturated with skills acquisition and entrepreneurship courses in virtually all the degree programs offered by the Nigerian universities (NUC, 2022).

I must admit beforehand that the kind of stuff we teach in the university is not epistemically and methodologically different from what is taught by other conventional universities in developed western nations we are always itching to copy. So, what is the fuss about Nigerian universities not being able to deliver on contents that are relevant to the demands of the 21st century knowledge-based society? It must be reiterated here that the debate on the relevance of conventional universities has everything to do with attempts to displace human agency in running the affairs of our postmodern world. All this frenzy is coming on the heels of the exaggerated potential of smart technology, artificial intelligence and robotics, the so-called technologies of the future, to tackle every conceivable human problem. On this basis, our children are expected to aspire to acquire high-tech skills for the ever-expanding horizons of knowledge economy. The future should be prepared to be run by autonomous, intelligent and “self-conscious” smart technologies as humans take the back seat to enjoy their “leisure time” and postmodern spirituality.

This debate is not new in Nigeria. It has been there all alone. It started in the 1980s with the need to concentrate on teaching applied sciences and engineering courses to facilitate the industrial growth of Nigeria. The necessity to go in the direction of science and technology started in earnest from the 1970s and 1980s, hence the allocation of 60:40 ratio between the arts and sciences. First, there is the misleading argument on the preferences of the sciences over the humanities; and also, the preference of applied arts and sciences over pure arts and sciences (Liman 2022). The hierarchy of value constructed around specific disciplines in the Nigerian university system is mostly out of sheer ignorance of the philosophical objectives of teaching disciplines in the humanities that we now consider irrelevant to the development of Nigeria.

Again, as the argument goes, skills are the sine qua non for the survival of every individual in the workspaces of the new knowledge society. The antagonists of the Nigerian university system see the university as a learning hub for the acquisition of “just” degree certificate. This is the mindset that encourages the questioning of the relevance of traditional universities and their epistemic structures by the purveyors of skills acquisition and virtual universities of the future. They have forgotten that disciplinary structures in the institutional sites, in our universities so to say, are all guided by emphasis on the unity of theory and practice, and the necessity to strike a delicate balance between learning activities in the classroom and laboratory experiments, fieldwork engagements and other out of the classroom instructional practices. If all the pedagogical approaches and methodologies that Nigerian students are exposed to by the Nigerian university system are not about basic skills training, I wonder what it is. It therefore means we are all ignorant of what skill acquisition is.

Anyway, in the argument of the proponents of skills acquisition, degree qualification can no longer prepare Nigerian children to adequately meet the challenges of the 21st century. In their reckoning, the new millennium is looking for skillful drivers of post-industrial society, a society based on unending quest for high-tech skills, knowledge economy, creativity and innovation. The post-industrial society is characterized more by the mystique of computer engineering, smart technologies, robotics and artificial intelligence as the online virtual professors seem to be suggesting. These technologies are said to hold a great potential with which to replace human agency in all facets of postmodern life. Therefore, the digital environment has presented the Internet and social media platforms as the alternative sources of the new knowledge economy. It is believed that smart digital devices and their learning applications can easily replace universities in the provision of knowledge and smart learning skills for the sleek realities of the 21st century world of computer algorithms, data science, machine learning and the technocratic power of the information society (Gleick, 2012).

In the argument of this paper, the purveyors of skills acquisition are surprisingly either people who are barely informed on the university system, or people that have deliberately decided to overlook the essence of higher order learning in any good university. The essence of a university is to develop the latent abilities of students to engage in theoretical reflection, critical thinking, philosophical inquiry, and to develop necessary competence to apply knowledge to all conceivable challenges in the social environment. It is not my intention to bother you with the ramifications of the social media debates here because I made my position very clear in a book chapter, and in an article published by two or three online news outlets. While the article in the online media has traced the history of philosophical debates on the value and function of knowledge, and its subsequent compartmentalization and hierarchization, the book chapter has specifically highlighted the relevance of the humanities for social development, because development is basically a function of our attitude (positive or negative) to society, economy and culture. We cannot have development without the appropriate mindset, without national consciousness a Frantz Fanon would argue. In short, it is mainly the disciplines in the humanities that have been constituted to play a key role in shaping our attitude positively to bring about a desired change to society:

As we know from our brutal social realities, terrible experiences, bad manners, folly, cultural decline; lack of refinement, finesse, sophistication and misconduct, impoliteness and incivility are all due to our gross neglect of culture, including its humanism, ethical coding and prescriptions. There are problems that have left much to be desired in our relationship with one another, and with other human beings. Philosophically, our inability to recognize the value, relevance, function of the arts and aesthetics; cultural development and conscious attempts at civilizational projects, are all at the roots of our collective despondency and maldevelopment (Liman 2022: 137).

One of the most insightful submissions on the prejudice against the function and relevance of conventional university is in the social media where the gospel of skills acquisition is popularized. Some social media influencers have blindly and “authoritatively” parroted the gospel of “skills not just degrees” with all the pretentious gusto they could muster to defend that false credo. In most cases, the veracity of what is being touted as gospel truth turns out to be unfounded claims, a blatant hearsay ferreted from half-digested sources. All the idle talks about the need to refocus the Nigerian university system to impart technical skills to university students by getting rid of traditional epistemes are hitherto considered irrelevant. The desire to kill critical thinking, philosophical inquiry and theoretical reflection in our universities is deliberately promoted for the expressed purpose of creating a specie of “subliminally induced capitalist consumption habit to further emasculate (the thinking faculties of) uncritical hordes of zombified humans” (Liman, 2023).

The vociferous call for the transformation of our universities into skills acquisition centers like some polytechnics is promoted by the ideologues of neoliberal corporatocracy who share abiding faith in the power of technology to solve all forms of human problems. These are coincidentally also the purveyors of a new world order and posthumanism and transhumanism ideologies. The whole brouhaha is geared towards “transforming our traditional reliance on value-free research in basic sciences and arts, which ironically is responsible for most breakthroughs in scientific inventions and discoveries as the evidence. of the last 200 years proved to us. Most of the breakthroughs in discoveries and technological inventions come about as byproducts of research in basic sciences” (Liman, 2022). The intention of the purveyors of skills rather than just degrees is to lazily smuggle their own ideas on how to refocus content delivery in the Nigerian university system to conform with the logic of supply and demand in an ever-expanding capitalist market economy:

The idea of marketisation of the university system that started in Britain and United States with the imposition of Thatcherism and Reaganomics was in line with public sector reforms against the welfare state. The economic reform policies endangered by Thatcherism and Reaganomics were against social sector spending, including the financing of public institutions that constituted themselves as obstacles to the creation of an unfettered space for full blown capitalist exploitation of resources and labour. Again, arising from those reforms most values were appropriated and subjected to the commodification and commercialization mantra of the market forces (Liman, 2023)

However, one of the most level-headed responses to skills acquisition debate I have come across on Facebook was made by Emakoji Ayikoye, a Nigerian Professor of Business Administration who teaches at New York State University, in a posting on the 17th of September, 2023. In his submission, he sought to demystify the myth peddled on the irrelevance of humanities and social sciences. Ayikoye is always making robust responses in his engagement with friends on issues affecting the wellbeing of Nigeria. In most of his postings on his Timeline he highlights issues militating against the development of Nigeria. On the specific argument on “skills rather than just degree”, he chimed his own contribution on the value of disciplines in the humanities and social sciences. He resolutely refuses to accept “the false narratives’, which promote the valuelessness of humanities and social sciences, especially in a soulless world saturated by quest for material gratification and deceptive allure of the wonders of technology. In Ayikoye’s view, “science makes the physical world work through creativity and innovation, and those trained in the fields of the social sciences and humanities are however the people that control global affairs”, including the ethical regulation of the products of science and technology as well as the fixing of “the renumeration of scientists”. I was indeed fascinated by the truism of his remarks. I was even more astonished when I discovered the nature of Professor Ayikoye’s academic background. On his realization of the strategic importance of humanities and social sciences to human development, without hesitation he abandoned the job prospects of his initial training in Pharmacology and Toxicology to pursue a PhD in Business Administration. He confessed that since his plunge into the epistemic world of social sciences and management studies, he “never looked back”; he never regretted his choice. According to him, the “practical world made more sense” … “ever since” with the insights he gained in his reading of social sciences and humanities.

At this point, I want to submit that the prospects and problems of disciplinary enclaves in the humanities, including language sciences and literary studies, in a world where everything that does not carry a brand logo is considered irrelevant. Studying languages and literatures in Nigeria today is no longer fashionable because such disciplines are said to have no market value. This erroneous perception is unfortunately gaining followers in the Nigerian society due to the widespread misunderstanding of the value and significance of language and literature for human development, and the character refinement they mediate.

The raging debate on the value of a university degree is a clear pointer to our gross misunderstanding of the value of a university degree, especially the value of humanities and social sciences. Social media warriors are brazenly telling us that a degree is not as good as skills acquisition, and innocent young people seem to be convinced about it. In this uninformed argument the role of institutionalized learning and education as the prerequisite of skills acquisition is totally overlooked. In fact, a degree certificate is equated to a mere paper qualification without commensurate value. In our fashionable knowledge society, skills acquisition is rated higher than the empowerment of a degree with all its potential to prepare and discipline students for all possible future engagement in skills that are suitable to their disciplinary background training. In fact, essential skills are basically acquired within the purview of the disciplinary structure of any good university. However, other forms of skills could easily be acquired through on the job training after leaving the university. The advocates of this false proposition are quite unaware of the fact that the learning processes in academic institutions involve not just philosophical inquiry, critical thinking and theoretical reflection, but inculcation of basic skills in the subjects that the university students obtained their basic training. Emphasis on both theory and experimental practices of the course content is absolutely necessary in every form of effective learning that combines the two. The practical component of learning in the Nigerian university system has always been the baseline for the mastery of any form of skill. Afterall, that is what the unity of theory and practice – laboratory experiments, workshops and fieldwork activities – is all about.