The author

Reproduced from the South China Morning Post which published it in a content partnership with POLITICO, the byline for the piece is that of Audrey Jiajia Li

- In China, Li’s passing triggered public outrage over the government’s suppression of vital information in the early days of the pandemic

- Months after his death, Li is being remembered for what he was like for most of his life: not a global hero, but a lover of fried chicken and TV dramas

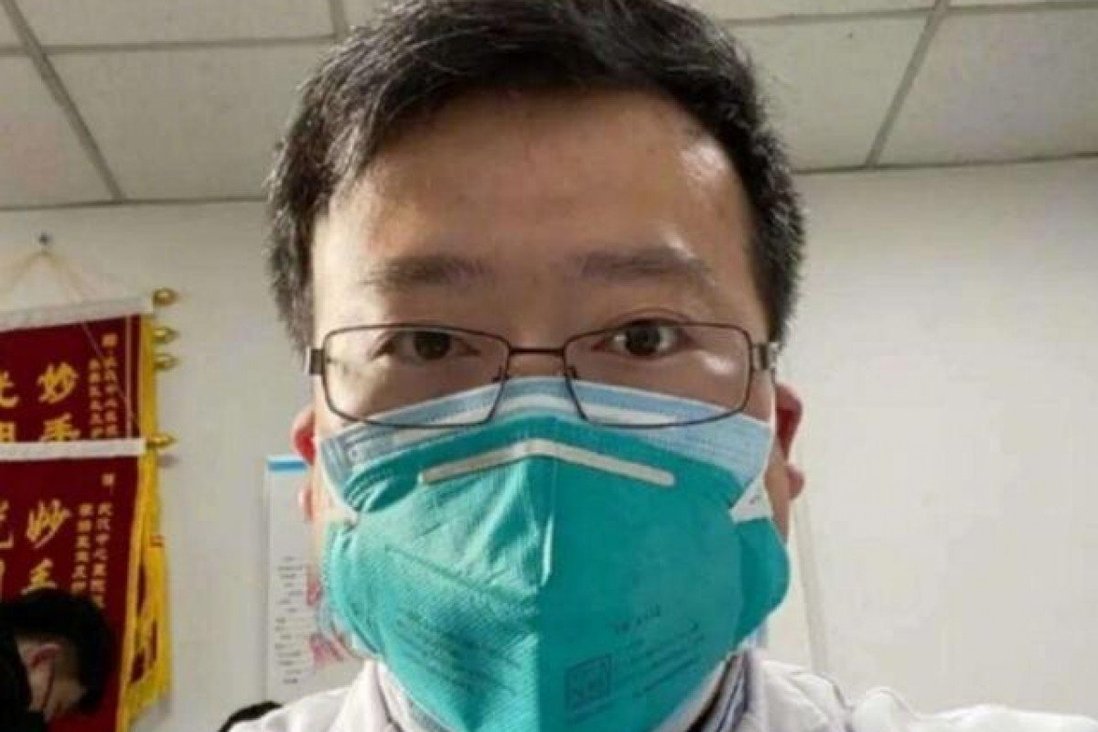

Dr Li Wenliang was an active user of Weibo, China’s Twitter-like social media platform, over the past 10 years. He posted his last words on February 1: “Today the nucleic acid test result turns positive,” he wrote of the test that confirmed he had Covid-19. “The dust has settled, and the diagnosis is finally confirmed.” He died less than a week later, at the age of 34.

An ophthalmologist, Li had sought to warn his colleagues at a hospital in Wuhan – the city that was ground zero for the coronavirus outbreak – of the then-unknown disease. In response, the police reprimanded Li for spreading “rumours” about something so real it eventually took his life. In the days and weeks that followed, across China and the world, Li came to be regarded as a courageous whistle-blower and a martyr for freedom of expression.

In China, his passing triggered an unusual level of public outrage over the government’s suppression of vital information in the early days of the pandemic. In a certain way, the outpouring has borne fruit, as over the past 10 months Chinese authorities have become more transparent about the pandemic. The government now releases daily reports about confirmed or suspected Covid-19 cases. Testing has been widely available. And doctors’ and scientists’ professional expertise is treated with well-deserved respect. Compared with the warlike situation at the beginning of the year, most people’s lives are now mostly back to normal.

But that does not mean people have forgotten the important role Li played in drawing attention to the deadly virus. More than 10 months after his death, his presence is still very much alive. As of early December, there were more than 1 million comments under his last Weibo post; only posts by China’s most popular superstars have harvested more responses. Yet the sentiments that drive people to pay homage to him have evolved.

A May 12th, 2020 Reuters pix of Chinese nurses taking part in the International Nurses Day at Wuhan Tongji Hospital in Wuhan, the Chinese city hit hardest by the coronavirus disease (Covid-19) outbreak in Hubei province. Source: China Daily.

Early on, Weibo users went to Li’s page to express sorry and sympathy. But more recently, they have expressed thanks. “This coming Chinese New Year I will be able to go back home to Wuhan and reunite with my family. Dr Li, thank you,” a Weibo user commented. Others simply go to his Weibo page to talk to him – about everything from who they have a crush on to how their day went to what their wishes are for the next year.

After reading his thousands of previous Weibo posts and learning more about the warm and kind soul he was, hundreds of thousands of strangers now regard him as a friend or a peer, even if they’ve never met him. Months after his death, Li is being remembered for what he was like for most of his life: not a global hero, but a lover of fried chicken and soapy TV dramas, just like most Chinese millennials.

It is said that in ancient times people would go into the woods to find a “tree hole.” They would tell their secrets to the tree hollow and then fill it with mud so the secrets would be sealed forever. Li’s Weibo account has become, in a sense, a modern-day tree hole – a place for people to share and confide. (Most people on Weibo do not use their real names).

The only time Weibo has seen anything like this kind of very public yet very personal outpouring was eight years ago, after a young Chinese woman suffering from depression died by suicide and left her last words on Weibo. Netizens who also struggled with depression flooded to her page to share their frustration and desperation.

Most people visit Li’s page seeking strength. “Wenliang, please allow me to call you that. I feel so powerless when it comes to life and work, and I always want to change. I think you had those moments too. Next spring, I will leave this city, I’m 40 already, but still am able to gather courage. I should follow my heart, would you agree?” one user posted.

His Weibo has attracted a range of life stories – happy and unhappy, confused and determined – as people grieve, vent, make wishes and seek solace. People also read each other’s stories and encourage one another. If the vibe was mostly sorrow 10 months ago, optimism has gradually found its way back – with a young doctor from Wuhan, perhaps improbably, ushering it in, and helping a nation to cope.

As one commenter said, “2020 was hard for me, but I managed to endure. Although there will be other difficulties ahead, I believe things will get better and better.”