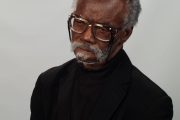

Nigerians and, indeed, the academic world are mourning the passing away of Prof Peter Ekeh early Tuesday, November 17th, 2020 in the United States. Most known for his 1975 essay, Colonialism and the Two Publics in Africa: A Theoretical Statement, it is, however, the same Prof Ekeh who took the categorical position that colonialism in Africa must be understood as an epoch, not an episode in the (un) making of Africa.

There is thus something puzzling in why people talk endlessly about his Colonialism and the Two Publics in Africa: A Theoretical Statement without always mentioning this, arguably, weightier intervention since the two publics argument is itself an outcome of colonialism. Ekeh may have died and be about going to his grave but with such a statement on how we might understand colonialism, it seems he would still be here with us for many years to come. This is in the sense of one, the question of which of those two works of his has greater weight and, two, the imperative of bringing back the debate which the Ibadan School of History originated as to what colonialism is: an epoch or an episode.

That debate ought to be the issue in Nigeria today because much of the issues in contention cannot be resolved outside of a much more involving thrashing of the question. If colonialism is an epoch, then the restructuring that is needed would be different from if it is just an episode. This is, therefore, a case of Prof Peter Ekeh is dead, long live Prof Peter Ekeh!

Although his death is a loss for global academia, the University of Ibadan is where he made the theoretical statement that drew global attention to him

The rest of the society might have to wait for those whose first degree, Masters and PhD the late Prof Peter Ekeh supervised at the University of Ibadan to get those kind of details that are generally not known about him. Only then would Nigerians, African, other academic colleagues and general readers may begin to know this real pioneer of the domestication of Western academic categories in the political analysis of non Western societies such as Africa.

There is something of a puzzle about that generation. Most of them studied outside the country in some of the best Western academies. In the case of Peter Ekeh, he went to the University of California at Berkeley. Although bred in the definitive hegemonic Western academic orientations, they came back home to turn those categories upside down as to make the African society subject of Political Science. To that extent, they could be said to have, consciously or so, started the decolonial process that is ruling global academia today. That is what one sees in taking a cursory look at some of Ekeh’s essays, for instance, irrespective of when they were written:

Basil Davidson and the Culture of the African State; Reforming Africa’s Estranged States; History of The Urhobo People of Niger Delta; A Tribute: Ulf Himmelstrand (1924-2011) and the Development of Sociology at the University of Ibadan and in Nigeria; Kinship and Civil Society in Postcolonial Africa; Social Anthropology and Two Contrasting Uses of Tribalism in Africa; The Impact of Imperialism on Constitutional Thought in Africa; Warri City & British Colonial Rule in Western Niger Delta; Social Anthropology and Two Contrasting Uses of Tribalism in Africa and so on and so forth.

One other thing they seem to have take seriously is reproducing themselves. It is such that Peter Ekeh is now gone but, starting from Ibadan to many other spaces he crisscrossed, one can find scholars who refract a lot of the Ekeh scholarly universe.

Of course, the point could be made that Nigeria has been unfair to Ekeh. The essay on how colonialism created two publics and the way that argument can explain so many of the stalemates in Nigeria today, for instance, might explain the perpetual reference to it. Its originality excuses that. But that is something to which he has written an Afterword in “Afterword: Notes on ‘Colonialism and the Two Publics in Africa: A Theoretical Statement” in 2012. Unfortunately, not many have heard, not to talk of reading and referencing the update because 2012/onwards Nigeria is not Nigeria of the mid 1970s. In 1975, there was optimism about Nigeria making it to being a power of some reckoning.

In 2012, despair had set in considerably and things like reading exciting new essays no longer count, even among many academics. The values have changed. What is the use of knowledge in a society where sycophancy and rough arm tactics are more profitable? Society has stopped reading or gone into some other metaphysical concerns and illusory categories from substantive issues of nation building. Again, only a re-tabling of the colonialism: epoch or episode debate may correct this sort of absolutism.

Lastly, Ekeh can be taken as one of the many signifiers of where Nigeria was heading before dark forces descended on her. Whether what remains of the national elite in Nigeria can still go into a conclave and reach a consensus on recovering the dream Nigeria from its local and foreign forces of nation breaking and put it back is the issue now!