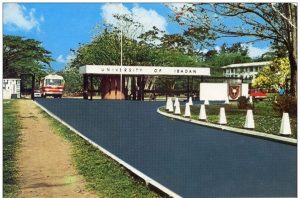

It could be the ways of God or just a happenstance. Whichever one it is, it is a very powerful convergence of angst against the conduct and outcome of gubernatorial elections in Bayelsa and Kogi states on the one hand and Prof Attahiru Jega’s wager on electoral anarchy in Nigeria. Convocation Lecture at Nigeria’s premier university, the University of Ibadan gave the Bayero University, Kano scholar-technocrat a platform Saturday, November 17th, 2019 that brought out the radical ire from a usually restrained Jega in matters of throwing labels. Anyone with a claim to have been reading Jega could sense trouble right from the opening of the lecture, with Jega descending on electoral formalism in a way that he should be allowed to speak:

Prof Attahiru Jega

Deeply embedded unwholesome practices, such as the pervasive use of money, violence, incumbency powers, and a wide range of electoral malpractices and fraudulent activities in the electoral process grossly undermine its utility as a vehicle for liberal democratic development. The mere regularity in the conduct of elections does not, in itself, bring about desirable democratic development. Rather, regularity of elections merely becomes a ritual, which does not yield substantive results or enduring benefits to the majority of the citizens, unless the preparations and conduct of, as well as participation by stakeholders in, the elections have integrity. Indeed, dominant political classes can, and often do, hijack the electoral process through various means, to access power for selfish and self-serving objectives, rather than for democratic development that would satisfy the needs and aspirations of majority of the citizens in a country. In virtually all cases, ritualized elections, which lack integrity merely serve to legalize, if not ‘legitimize’, access and control of power into executive or legislative arms of government by people unconcerned with, or indifferent to, the requirements of sustainable democratic development. Hence, such elections do not catalyze, nor guarantee responsive and responsible representation and/or governance.

This pronouncements matter because, by the criterion of ‘hierarchy of credibility’, Attahiru Jega is an authoritative voice on matters election in Nigeria. He is not only a scholar of Political Science where Elections constitute a research domain, he has also been the Chairman of the national election management body in Nigeria – the Independent National Electoral Commission, (INEC) angrily renamed Inconclusive National Electoral Commission in the wake of the February/March 2019 General Elections by sufficiently angered stakeholders.

So, it is crucial that he says the ground has now decisively shifted from what he calls spurious theoretical postulations with a pre-supposition that periodic and regular elections would catalyze democracy and good governance to scholars coming around to recognize that only elections imbued with integrity can contribute to regime legitimacy, stability, and good, responsible and responsive governance in a modern nation state.

Linked to what was happening at the time Jega was making these statement, it will be no mischief to infer that Jega was descending on the conduct of the guber elections in Bayelsa and Kogi states where every inconceivable manner of brigandage were employed to produce victory. A leader think tank – the Centre for Democracy and Development, (CDD) which comprehensibly monitored the two elections has called it a sham, calling on President Muhammadu Buhari to clear the mess. Other flanks of the civil society have made similar points to CDD’s, forcing Yahaya Bello, the one declared by INEC in the case of Kogi State to declare that the violence during that election was not enough to interrogate his victory. Uhmm!

As far as Jega is concerned, the Nigerian electoral process has historically been flawed, and replete with profound challenges in all the three key phases. He itemises the phases and key electoral malfeasance as

Pre-election phase:

- Inadequacy and/or inconsistency of the legal framework for the conduct of elections;

- Epileptic, insufficient and delayed funding for the elections;

- Inadequate and/or unfocused sensitization, public enlightenment, political and voter education;

- Inadequate EMB engagement and sharing of information with the key stakeholders (i.e.: political parties, candidates, civil society organizations, security agencies, the media);

- Over-bloated and/or ‘incredible’ voters’ roll (Registration of voters);

- Lack of a level playing field for parties and contestants in the pre-election campaigns, which obstruct competitiveness;

- Costly and corruption-laden pre-election litigation, associated with undemocratic and fraudulent conduct of party primaries.

Election-Day Activities:

- Poor arrangement for, and deployment of, personnel and logistics;

- Lack of transparency and accountability, and corruption in the management of polling units and collation centres, as well as with regards to the compilation, transmission and announcement of results;

- Chaotic and ineffective arrangement for reverse logistics after elections;

- Ineffective and inefficient management of the polling units and results collation centres, due to lack or inadequacy of training of poll workers;

- Insecurity, conflicts, violence and disruption polling day activities, due to inadequate and ineffective role by the police and other security agencies;

- Crass harassment, intimidation and/or inducement of electoral officials;

- Commission of Electoral irregularities and offences by key stakeholders.

Post-Election Phase:

- Lack of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms;

- Costly and corruption-laden post-election litigation;

- Poor storage and archival of sensitive election materials, which denies litigants access to original official records of elections;

- Inadequate and/or poor review, assessment and evaluation of the conduct of an election, which constrains the factoring of ‘lessons learned’ into the preparations for future elections.

This checklist is what many parties to elections in Nigeria would keep because it is coming from the horse’s mouth as it were. And Jega is saying all these challenges have manifested in varying forms in every election since the First Republic, culminating in the 2007 elections which he says most observers and analysts regard as the worst in Nigeria’s history.

The EU saus the 2019 elections were challenged in many regards

Not only have much of these challenges manifested since independence, it is still a case of All the King’s men and All the King’s horses still not being able to prevent Humpty Dumpty from falling.

To quote Jega again, “In spite of series of reform measures aimed at raising the bar of electoral integrity since 2010, many embedded malpractices have remained unresolved, and the integrity of Nigerian elections leaves much to be desired”. And he provides the proof in logistics of deployment and retrieval of elections materials remaining a formidable challenge just as use of money and incumbency power as well as vote buying and other violations of campaign finance laws and regulations.

What some interested parties are likely to consider scary in this testimony is the revelation that as politicians come to the realization that deployment of technology is blocking the efficacy of some of their traditional malpractices, they are now increasingly resorting to buying votes and inducing security agencies to look the other way while this goes on at the polling units. What this suggests is that technological fix to electoral anarchy is being subverted.

Curiously, Jega believes that continuous legal and administrative reforms, as well as sensitization and public enlightenment is the way to go as far as restoring and protecting the integrity of elections in Nigeria. In fact, for Jega, what is called for is all stakeholders strengthening their constructive engagement with the electoral process, with a view to improving, protecting and defending electoral integrity. That is, he thinks that critical stakeholders, individually and collectively work together and engaging with the electoral process can eliminate or reduce the range of all malpractices bedeviling the electoral process to the barest minimum.

He, therefore, did not have any difficulty in thinking that professors, lecturers and students have significant constructive roles to play, that “they can play these roles in the contexts of research, training, advocacy, mentoring and in electoral administration”. The former INEC Chairman provides a fairly uncontroversial outline of the spaces by which this task can be accomplished in relation to electoral integrity.

Zeroing in on research, he assigns to universities investigating, analyzing and understanding the nature, extent as well as dynamics of electoral malpractices and the obstacles and constraints to electoral integrity in the Nigerian context. And this will not only be by social sciences alone but also by the sciences and technology disciplines, what with technology increasingly being deployed in elections. He can see the social and management sciences such as psychologists studying voting patterns, psychological dispositions of voters and candidates, candidate characteristics, type and nature of voter education and sensitization, administration and management of elections, deployment of logistics, and so on. Elections remain, after all, among the most rigorously, empirically and scientifically understudied, he says.

In search of rescue from electoral anarchy the universities through research, advocacy, mentoring and electoral administration

To research, he adds advocacy, training, mentoring towards attitude change at a critical mass level and, lastly, electoral administration: improving electoral integrity through such innovations as use members of the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC), students and senior academics in several tiers of election day administration such as polling unit management on election day to result tabulation and declaration. Resorted to as a response to rapidly deteriorating integrity in electoral administration since the 2011 general elections, Jega insists it has been commendable as, according to him, only in few instances of state governorship elections (e.g.: Rivers in 2015, Anambra in 2018, Imo and Kano in 2019) were there serious allegations of attempts by the politicians to influence some of those involved. For him, there is no need throwing the baby away with the bathwater. “What has essentially worked well, needs to be retained, perhaps repositioned and improved upon for greater value-addition to the integrity of our electoral process. As we strive for even more remarkable improvements to the integrity of our electoral process, we should also strive to identify and utilize credible persons into electoral administration from other sectors of the Nigerian society, such as professional associations of lawyers, doctors, engineers, and so on. In any case, academics should continue to be used, but with greater screening and vetting to ensure that the few bad eggs within do not in connivance with crooked politicians penetrate and compromise the integrity of electoral administration”.

For those who would argue that universities are themselves bedeviled by enormous challenges, Jega has an answer. While acknowledging profound challenges confronting the universities, he argues that these are intricately connected with the seemingly larger, external issues such as challenges to electoral integrity and democratic governance, which if addressed, would pave the way for easier resolution of the internal challenges. He has thus no problem concluding that “university communities, with enlightened collective interest, can and should be positive agents to bring this about”. It sits pretty well with his overarching view that it is quite possible to bring about a thriving democracy in Nigeria, “in spite of the evident challenges”.

If this is the testimony of the most innovative election management chief in recent Nigerian history – introducing the card reader in 2015 – then Jega’s UI speech is beyond the role of the universities but also a sermon and a summoning