Intervention Accademy

Since Prof Absalom Mutere, the late veteran media trainer, made the startling disclosure about how so many African journalists have neither heard and could thus not have applied the concepts... Read more

A new book scheduled to make its entry into the market later this week has gotten the Western world up in arms against the Postmodernist paradigm and its key contention that there are no suc... Read more

Academia has a new entrant. Throughout this piece, the said entrant would be known and called Dr. Olu. No disrespect is intended in this naming system. It is for simplicity. It is avoidance... Read more

Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria is still defining the space of conflict, within and beyond the country. A consortium of nine universities in Canada and the Lake Chad basin countries of Nige... Read more

Mallam Yakubu Aliyu, a student of Prof Ahmadu Jalingo as well as a versatile student of Nigerian politics in his own right has sent a ‘rejoinder’ to Intervention’s piece carried yesterday on... Read more

Chinua Achebe, generally regarded as the “grandfather of modern African literature” may be dead and gone to his grave but without that ending his engagement with Nigerian politics. Thi... Read more

All those calculating to read Agricultural Sciences are in for a free ride. Dr. David Oyedepo, the Chancellor of the university, is incentivising such prospective students in Crop Science, A... Read more

The university system in Nigeria is still not off the critical gaze of its assessors. But unlike the recent past when it was the Federal Government and university administrators throwing dar... Read more

Would the quality of education in Nigerian universities be raised by mobilising and injecting Nigeria’s reserve force of well heeled professors and senior academics who have left the system formally but are still capable of, individually and collectively, making a decisive contribution to the re-making of education in Nigeria?

This is the question on a considerable number of lips now partially in response to the spate of grudges against the system recently. A prominent Vice-Chancellor told Nigerian undergraduates recently to leave Facebook and face their books. The Nigerian government is complaining. The World Bank complained much, much earlier. Even the regulatory agency –the National University Commission, (NUC) is threatening a reform whose dimensions no one knows yet. All of them are raking against the university system, particularly on the overall quality of education.

Prof Mike Adikwu, VC of FG own University of Abuja and proponent of the postdoctoral research strategy

So, haven’t the dynamics worked out in such a way that it is time to construct a pact between the Nigerian government and Nigerian academics who are though formally retirees from the system but can be pulled back. Pulling back the category of retirees into the system has been reinforced into currency by the recent argument of Professor Michael Adikwu, the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Abuja that there is no other way to resolve the crisis of quality in the university system other than an aggressive pursuit of the postdoctoral research strategy as opposed to the illusion of dealing with the crisis from below. Critical observers of the system are thinking that it is even the starting point of the Vice-Chancellor’s proposal because the entry of that quantum of well versed elder academics prepares the ground for producing PhD materials that can go out and engage the system while also increasing the quality and quantity of PhD products domestically and immediately.

The argument is that these professors and senior academics are all very much available, the engagement can be immediate and the resources required to put them to work is minimal. They are not going for battles for Vice-Chancellorship, HODs, competition for research grants and any of those things that creates tension on campuses. They are not on the wage bill of the individual universities and there is no university that cannot find offices for its own quota of that pool. At 164 universities, it is very unlikely that each university would get more than two, depending though on what formula for sharing is approved.

Above all, the idea is argued not to be that strange after all. The late Prof Takena Tamuno was around and about at the University of Ibadan and even writing and publishing almost till he breathed his last. At 80, the late Prof Abiola Irele was still teaching at the University of Ilorin before his death. And even now, there are those such as Professors Asobie, Toye Olorode and Dipo Fashina still teaching, one way or the other, after retirement. Prof Biodun Jeyifo spends his time between the US and Nigeria. He can be doing something on a Nigerian campus each time he is around. So, the Nigerian government can pull back most if not all retired academics in and around the country to contribute to managing what is believed to be some kind of emergency in the university system, if the range of people complaining about the system is anything to go by.

These are no ordinary academics. Most of them have gone to the best schools around the world. If you take those that emerged as leaders of the ASUU, Biodun Jeyifo went to Cornell University, Mahmud Tukur to ABU, Zaria, Asisi Asobie to London School of Economics, the late Festus Iyayi to Kiev and later Bradford in the UK, Attahiru Jega to Northwestern University, Dipo Fashina to the University of California, Los Angeles and so on. There is nothing like the best university but these are some of the most outstanding elite universities in the world. Even people who knew Prof Asisi Asobie long before now were awed when his citation was read at The Electoral Institute’s First Abubakar Momoh lecture last Thursday. And that is what one finds with most of them in that generation. So, why would such collection of people who are sound, committed and available not be pulled back and injected, goes the question.

Igbinedion University, Okada’s Prof Eghosa Osaghae, VC with awesome CV

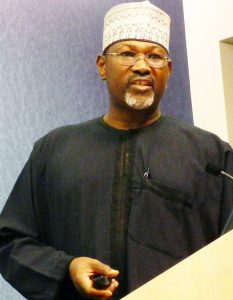

Prof Attahiru Jega, experience spanning ASUU, VCship, INEC Chairman

Such a list would stretch from those who have completely retired but are not tired; those who are either on the verge of exit from the system or are serving as Vice-Chancellors and might not move into other things but can still assist the system somehow; the category that are not currently teaching because they are on government service but are irreplaceable and, finally, there are those in NGOs who are, nevertheless, mobilisable. A sampler of the list across the different categories would stretch from Professors Enoch Oyedele, Okello Oculi, Y.Z. Yau, David Ker, Asisi Asobie, Egite Oyovbaire, Isawa Elaigwu, Yakubu Aliyu, Bolaji Akinyemi, Adiele Junaidu, Idowu Awopetu, E. R Ajayi, Moses Ola Makinde, Soji Amire, Kola Torimiro, Prof Dandatti Abdulkadir, Oga Ajene, Tony Edo, Mike Kwanashie, Eghosa Osaghae, Alli, Alemika, Alubo, Sule Bello, Nuru Yakubu, Toye Olorode, Dipo Fashina, Sonny Tyoden, Jibrin Ibrahim, Alex Gboyega, Bayo Adekanye, Okechukwu Ibeanu, Sam Egwu, Ogaga Ifowodo, Adebayo Williams, among many others that cannot be recalled immediately. It is difficult to place Yusuf Bangura on the list.

Some people estimate that no less can 2000 can be compiled. The assumption is that Vice-Chancellors would be disposed to such an arrangement, especially those of some of the new, private universities that are most conscious of standing out from the crowd.

There was a time they were chased around mainly for “teaching what they were not supposed to teach”. This was the ‘crime’ the state imagined them to be committing and which was framed as such by the late General Emmanuel Abisoye, one of the most sophisticated intellectuals of the Nigerian military in his time and who was head of government investigation into student uprising in Ahmadu Bello University in the mid 1980s. On its wisdom, the state went after ‘them’, mostly those in the leadership of the Academic Staff Union of Universities, (ASUU). Today, the government itself is in the forefront of complaining that the university system is not performing its role to the state and that university workers were right in their perspective of the crisis. It is in that context that some stakeholders assume that government is most likely to look into Professor Adikwu’s argument, he being the VC of Nigeria’s capital city university. But even if government accepts the idea and finds the money, how soon can it produce outcomes without an emergency measure such as injecting tested and untainted academics?

Their presence, it is argued, would be a mentoring system in itself. “Their mere presence on the corridors of Departments means that certain things wouldn’t happen, younger academics would get the benefit of solid processing and they can best handle certain core courses such as theories and methods, especially at the postgraduate level”, it was argued. The clincher appears to be the question as to whether anybody would say that there wouldn’t be a big shift if Nigeria can inject 1000 solid academics into the system today, meaning that they would be coming as guides, especially in designing the courses which some academics say is more crucial that delivery of courses.

It was one of the questions Intervention tried to deal with very early in its formation. The puzzle is why more conflict and violence in Nigeria at a time there are more universities and think tanks dealing with formal study of peace and peace politics? The question came about following what was clearly a massive expansion in opportunities for formal study of Peace and Conflict in Nigeria, something that was available in scattered forms in International Relations, Sociology, Psychology, Political Science, Geopolitics, Linguistics and Religious Studies.

Whereas by 2003/4, it was just the University of Ibadan programme in Peace and Conflict Studies and the same university’s Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, (CEPACS) as well as Programme on Ethnic and Federal Studies, (PEFS), there were over 20 universities, INGOs, independent think tanks and sundry centres offering one programme or another in Peace Studies by 2016. The correlation should be very clear and if that is not the case, then the question must be posed regarding what might be the intervening variable between the reality of more such centres without corresponding decrease in the quantum of violent intra and inter-group conflicts. Intervention interviewed academics and other stakeholders across the country in a two-part narrative. Each gave his or her own analyses, (See “Nigeria: Why the More Conflict Management Training, the More Conflict, Sept 5 & 6th, 2016/www.intervention.ng).

Pioneer Peace and Conflict Studies centre in the Nigerian university system

An expert from the Peace and Conflict programme at Ibadan who assessed the story post publication, however, interrogated the assumption entirely. He said the expansion under reference was overblown because many of the centres and Peace Studies programmes lacked the staff strength and the vibrancy to warrant a claim of lack of correlation between expansion in the number of study centres and decrease in (violent) conflicts. That was 2016. Now, this is 2018 and there is a book trying to account for the relationship between universities and conflict.

It is an interesting book because, for one, it has analysis from across different parts of the world – Middle East, Asia, Europe and Africa. It may not score an ‘A’ in inclusivity because there is just a chapter from (South) Africa, it is an improvement when compared to other such efforts.

Two, it basically agrees with the notion of universities as conflict managers in their own right because they are theatres of discourses of conflict, discourses which are reproductive of peace as well as conflict, depending on what the discourses are and how students of these discourses operationalise them.

The newness of this research agenda means that most readers would find the introductory chapter and Chapter Three interesting. Chapter Three is where Dr Sansom Milton of the Centre for Conflict and Humanitarian Studies at the Qatar based Doha Institute for graduate Studies reviewed the literature on universities and conflict. Those who are, however, more interested in practical issues might find the case studies chapters (4 – 11) more inviting. The case studies in university – conflict nexus cover some of the hottest conflict spaces or universities concerned with the discipline: Israel/Occupied Territory, Myanmar, Belfast, Bradford, Bosnia and Herzegovina, South Africa.

Dr Millican of the University of Brighton and editor of the new book

Edited by Dr Juliet Millican of the University of Brighton in the UK, this book contributes to closing the gap on scarcity of reading materials in a discipline still borrowing heavily from other disciplines and trying to resolve fundamental subject matter issues. Only last month, Professor John Gledhill of the University of Manchester published an article calling for an intellectual insurgency to put peace back into Peace Studies because much of the works in the discipline so far are concentrated on violence/war compared to peace and peacemaking. That could sound strange to students of Peace and Conflict in Nigeria, for example, given the strong distinction between Negative and Positive peace in Peace Studies on campuses across the country. However, Gledhill made his call based on a study he carried out last year with Jonathan Bright at the Oxford Internet Institute, Oxford University in which they described Peace Studies as a ‘divided discipline’ on the basis that “there is limited exchange between academic studies of war and research on peace”. It is possible because the quantum of Peace and Conflict Studies and publications coming out from Nigeria might be so minor of global percentage as for the two scholars to make their claim.

In all cases, this is an interesting time than any other to study and/or practice peace. This is simply because the world is still in the Interregnum: the old order is so discredited and going but the successor order is still nowhere to be seen, leaving not a void as such but an empty space upon which anyone could smartly write anything.