On June 27th, 2024, the burial rites for Rose Amina Ada began in Olabe in Ajegbe Village of Ohinmini Local Government Area of Benue State in central Nigeria. It should be over now. A month and a day ago today, Madam Eliza Ajuma Adulugba (aka Eliza Junior) was buried in Efoyo in Edumoga District of Okpokwu LGA of Benue State. In less than two weeks from now, the world will say good bye to Josephine Ella at Ogene Amejo in Okpokwu LGA.

These are not the women that most readers of Intervention would be familiar with. They are not the women who made the headlines. But these are the women who made some of the people who make headlines today or some of those who made some of those who write for Intervention, for instance, and who are, therefore, actually the real writers, in Intervention and elsewhere. They would take a large share of the media coverage of the everyday if not for the city – centric character of journalism generally, they being the most potent bearers of the defining parameters of communal authenticity, the same parameters with which they molded some of us and for which we cannot be grateful enough to providence.

In other words, the women in this piece are not newsworthy only by association with moulding some of us but also because they are newsmakers of the environment in which they were the individuality by which the metrics were measured. It is thus a privilege to cut into their life stories even as that is possible only from how one experienced them. Let’s start with Amina Ada on the ground of seniority.

Late Mrs Amina Adah

There was an image of Mrs Adah which preceded her to the village where some of us were growing up. She was represented as the tough wife of Francis Adah. Francis Adah was a notable’s notable in communal terms but even above that, being one of the very first set of textile workers taken from Nigeria to the UK for advanced training in managing the emergent textile industry in and around Kaduna. By the time he retired from the Kaduna Textiles Limited on the eve of Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) in the mid-1980s, he had been to the UK for one training programme or the other three times and risen to Personnel Manager at KTL. Unlike Okpani Ochiga, his senior from the same village in that factory, Adah was not a trade unionist. But he was no less a radical.

Amina’s stature was largely derived from association with the Adah mystique. Of course, Adah was a ‘big man’. The coloniality of being as a key part of the African experience of history meant that anyone who had been in the UK and obtained specialist training like him was a ‘big man’ in the sense used across Africa and marked, in his own case, by a big company house, a prestige car and capacity to open recruitment opportunity into the textile factories for the hordes from the base.

His wife was thus bound to be respected and/or feared as the case may be, more out of perception than the actuality of it. There was a second reason for that. Francis Adah loved education. He brought several young men from the village, fixed them in different secondary schools and was exercising panoptic oversight on their progress. These were assertive young men who were bound to do one thing or the other which would irritate most housewives, especially as it related to intrusion into the kitchen.

Other than that, it was difficult to see anything ferocious or aggressive about her when it was our turn in the Francis Adah household. ‘Our turn’ here refers to time that the now late Peter Abah and myself became part of the household in the 1980s. Peter Abah was the last of Adah’s investment in education for kindred elements. It was Peter Abah one knew and whom one followed into becoming a member of that household. Yes, you became a member of the household because there was no one Francis Adah could not relate with. Your age didn’t matter to him. He cared about no such protocols as who eats gizzard, for example. For reasons one cannot fathom immediately, the gizzard has been discursively constituted outside of the part of the chicken forbidden to women and children. Only elders were allowed to eat it. It was until one came to Francis Adah’s house in Kaduna that one discovered it was a discursive move by elders.

When it was time to rent own house after miraculously being employed in Radio Kaduna in 1982 in the aftermath of a failed attempt to enter the School of Basic Studies, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, he said: why do you need to leave. If you don’t want to stay in the main house, you can take over the Boys Quarters. He would explain how he locked the place because his first son would be coming home late in the night if he allowed him to stay there, a control system he said did not apply to me as a worker in my own right. As long as one lasted in Adah’s household, Amina, his wife wasn’t a problem.

In any case, with eleven biological children – Onyowo, Patrick, Onyeche, Philo, Oko, Danny, Helen, Ogeidu, Blessing, Rebecca and Mary – she earned her place over and over and whatever happened, she was deserving of respect. So, one solemnly mourns her passage.

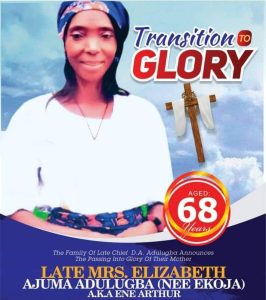

Late Mrs Eliza Adulugba

Next is Eliza Adulugba (aka Eliza Junior). One came to know here the moment Chief Daniel Adulugba, the District Head of Edumoga at the time assumed one’s guardianship ahead of entry into Emmanuel Secondary School, Ugbokolo in the late 1970s. It meant being in the District Headquarters and in the boarding school as and when necessary. There was no problem with that except that, by this time, the first set of the chief’s children had finished secondary school and left for the towns. What that meant is that the section of the District Headquarters at Olanyega which, historically, served as accommodation for Chief Adulugba’s senior cum male children was to be occupied by one alone whenever in the District Headquarters. That was still no problem except that, coming from the hamlet with deep fear of darkness, one had a problem of sleeping alone in darkness. Tales by moonlight had inducted into one the belief that darkness is co-terminus with freely circulating ghosts, spirits and all such non-human entities.

So, in spite of the reassuring presence of Chief DA Adulugba who encouraged me not to, as a man, manifest fear in a house full of women, one became a problem every night when it was time for everyone to go to bed. Only two of Chief’s wives could solve the problem by coming over to the outer accommodation to stay until they noted one had fallen asleep. That was the only way to solve the problem because shadows and darkness were some people’s antithesis for a very long time. That approach, for all we know, might have been constructed by Chief himself but even if it were, the two women – Eliza Junior and Enochigbo – implemented it faithfully. Naturally, a bonding developed between myself and the twosome but no less with all the others. And that bonding has persisted. Naturally, her sudden death at just 62 was bound to be upsetting. She and her colleague must be put on record for contributing to one’s breeding at a time one could not have helped one’s self.

The last but not the least is Josephine Ella. God gave the late Josephine figure and awareness about carriage that enhanced her personality. The two combined to give her elegance that made it difficult for anyone to ignore her whether one liked or disliked her. Of course, she was a socialite, at ‘home’ and away from home as can be seen in her career in a military establishment. She coped beautifully with Lagos, parts of the South and with Abuja. As the late Chief Hyacinth Ede was used to saying, such is an achievement for anyone from rural central Nigeria in contrast to the majorities who exercise various forms of veto on Nigeria. The late traditional title holder must have a point. Josephine’s cosmopolitan credentials is a score for her.

Late Mrs Ella

But the real touching elements about Josephine was her sense of carrying herself with dignity, even when in pains. And then there was her personal though indirect gesture which one must publicly acknowledge to her credit and appreciate.

This short piece brings something else to the agenda – the need for a much more comprehensive compilation of those who helped one to cross one nasty bridge after another since one left the radius of parental and communal care that came with leaving for secondary school. As Labaran Maku once noted, one has survived on a vast network of charity ever since leaving for secondary school from the security and comfort of the hamlet. Implied in that is the challenge of community responsiveness and the associated debate about how best to do that. Go about distributing cash to people? Or take projects home? Or buy rice, wrapper, Omo and sugar for the folks?

The right approach is none of the above. These practices are nothing but the apologetic behaviour of a confused elite that has bungled social transformation. The task is to achieve social transformation for our people. Replicate Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, if China’s is too huge a transformation to mention. Integrated social transformation is what every national elite owes its folks. It is the historical mission of national elite everywhere in the world. Why that is not part of the conscience of the African elite is the puzzle in history. Is it the viciousness of the cultural decapitation that accompanied colonialism in Africa that has made the African elite to have no shame or is the viciousness of contemporary global capitalism that has made the African elite to be so slavish? Both Malaysia and even Singapore told the IMF off and nothing happened to them. But both our military and civilian elite worship the IMF and the World Bank more than they worship God.

It must be mentioned that it is not that some of us have not done or even overdone the pathway of personal responsiveness to the problem of mass communal poverty. It is that that is not the pathway for liberation for the mass of our peasants from mass poverty and misery. There is, therefore, no alternative to politically organising. Each time we mourn any sets of the departed as we do now, we must remind ourselves of the limits of unstructured ‘stomach infrastructure’ approach or the deceit in elected political leaders hiding under ‘foreign investment’ trips to siphon public funds. And then draw attention to the imperative of the challenge of a social transformation. It is a collective shame for all of us in Nigeria and the occasion of mourning the passage of three stalwarts of those who produced us from ‘home’ is an appropriate occasion to beat this drum.

We have lately been educated to come to terms with the theology of predestination which rules out anything such as untimely death. Predestination rules out untimely death because whatever time one dies is what has been written for him or her from the beginning. Predestination can be thus comforting.

Adieu, a threesome!