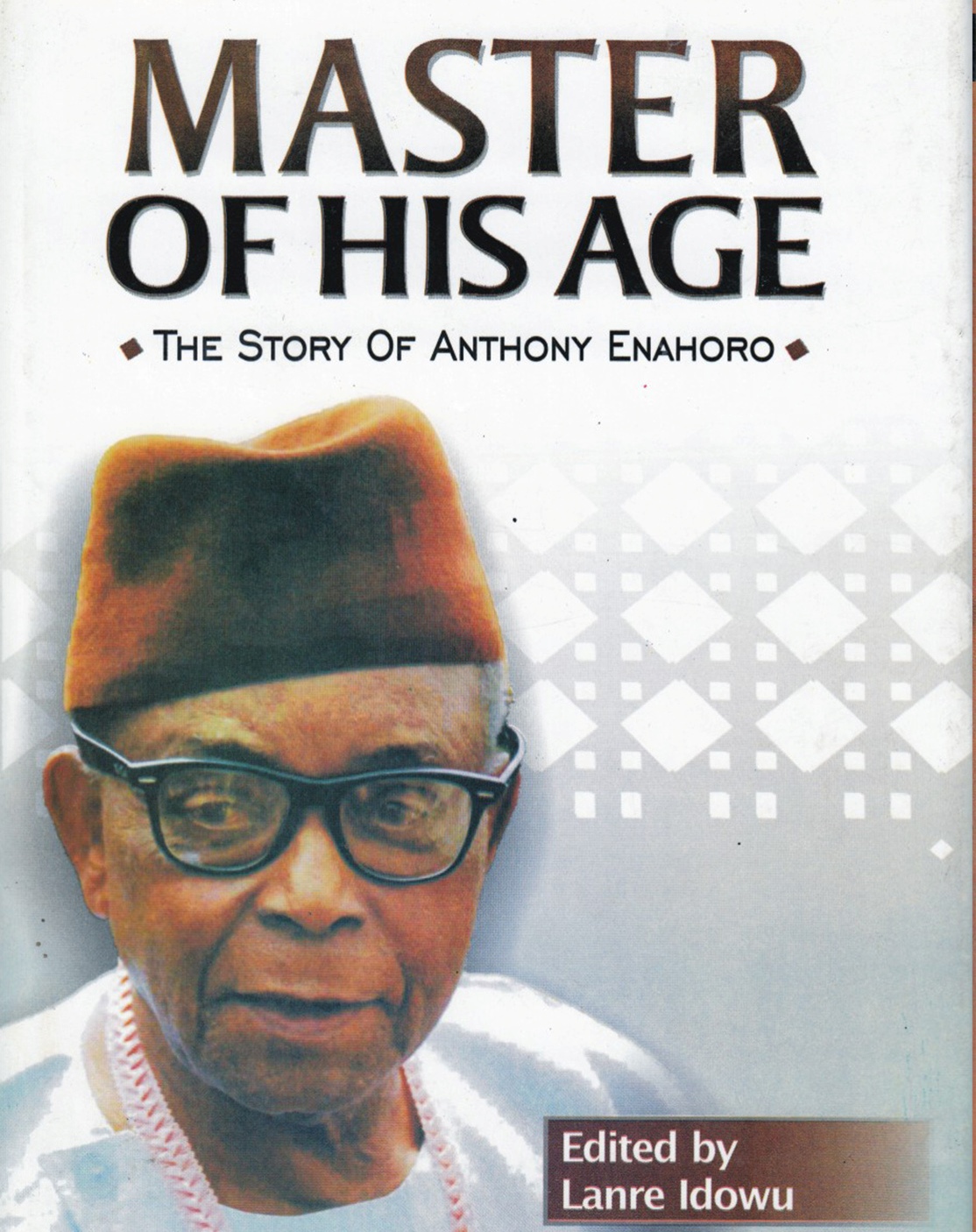

The author

By Manni Ochugboju, Esq

A legal activist goes behind the headlines to unpack why foremost Nigerian nationalist, Chief Anthony Enahoro, is perhaps the first person in the world to have received two presidential pardons, one from General Yakubu Gowon and a second from President Muhammadu Buhari. It is a treatise!

Flanked by the Attorney General of the Federation and Minister for Justice, Abubakar Malami (SAN) and the Minister for Information, Alhaji Lai Mohammed on Thursday April 9th, 2020, the Minister for Interior, Rauf Aregbeshola, announced the presidential pardon granted the late legendary nationalist hero, Chief Anthony Enahoro CFR. The announcement was made along with those of four others viz former governor of old Bendel State, Prof. Ambrose Alli; Lt. Col. Moses Effiong; Major E.J. Olanrewaju and Ajayi Babalola as well as a further 2,600 inmates approved for release as part of measures to constrain Coronavirus by decongesting the facilities of the Nigerian Correctional Service.

The Ministers mentioned “compassionate grounds” but did not take time to sufficiently articulate the reasons that informed the prerogative of mercy granted Chief Anthony Enahoro, and the four others. As a consequence, we have seen dozens of views on the amnesty, all of which are silent on the reasons why the pardon was granted. But worse, an assortment of misconceived, colourful narratives are being spun, either out of ignorance or for political or malicious reasons. Some narratives even allege that the pardon was granted in error. It has, therefore, become an imperative to adduce reasons for this significant redress of historical military injustice suffered by the late nationalist hero.

Issues Joined

In the wake of the July 29th, 1975 military coup, General Murtala Mohammed’s anti-corruption crusade, continued by his successor, General Olusegun Obasanjo, a Military Tribunal sitting in secret as it were in 1976 was said to have indicted Chief Enahoro. The Supreme Military Council on July 4th, 1977 affirmed the indictment for allegedly, “corruptly or improperly” enriching himself. This vague indictment suggests that, so long as your “enrichment” is perceived or adjudged to be “improper”, even if it is not corrupt, or dishonest, you are guilty as charged. This is military persecution, nay, prosecution, supposedly. Although an indictment is not a conviction, the Supreme Military Council made an order that was, in effect, a declaration of guilt, turning the presumption of innocence upside down. And that declaration also included an obnoxiously oppressive forfeiture order. It is this outrageous stigma, arising from military tyranny, that Chief Enahoro’s son, Mr Gabriel Enahoro wanted to quash when he instructed a lawyer in 2013 to apply for a posthumous Presidential Prerogative of Mercy.

The Supreme Military Council, (SMC) which instrumentalised the Military Tribunal in question

The said Military Tribunal that indicted Chief Enahoro in 1976 were said to have conducted their proceedings under a 1968 Decree 37, The Investigation of Assets (Public Officers and Other Persons) Decree, and Public Officers (Special Provisions) Decree 10 of 1976.

The forfeiture Order of the Supreme Military Council of July 4th, 1977 decreed that Chief Enahoro had “forfeited to, and shall vest in the Federal Military Government free of all encumbrances and without any further assurance…” almost all his assets and properties. This tyrannical forfeiture order has continued to torment the ghost of Chief Enahoro, his children, grandchildren and Estate to this day.

It is pertinent to note that most of the assets confiscated by the Military regime were acquired by Chief Enahoro between 1953/1959 before Nigeria got independence. And none of the properties had any bearing with the pervasive allegation of corrupt practices that the Military Officers were charging politicians and former public office holders at the time. It was canvassed that it is not in the public interest for the Military Government of 1976 to direct inquiries into assets that were acquired by Chief Anthony Enahoro, from 1956. Neither was it in the cause of justice for the Military Government of 1976 to, retroactively, apply a decree of 1968 and 1976 to confiscate properties acquired under British colonial rule.

The provisions of Section 6(6)(d) of the 1999 Nigerian Constitution, as amended, ousts the jurisdiction of the Courts from determining any action, proceedings or existing law made under the Military Government. As Chief Enahoro could not take his case to court in his lifetime, canvassing his case for posthumous pardon, from the days of President Jonathan Goodluck to that of the incumbent who was a Military Head of State and member of the Supreme Military Council that endorsed the original sin to be redressed was a high wire balancing act, treading on eggshell as it were.

One of the affidavit deposed to by Chief Enahoro and a few documents dating back to 1958/1959 including title deeds, were tendered to plead his innocence in the context of the cloak and dagger, oppressive and secretive character of Military Tribunals of the last century and of limited access to classified documents and Chief Enahoro’s own extenuating documents having been confiscated by the Military authority. Questions were asked if any proper investigation or inquiries were conducted before the order for forfeiture was gazetted. Serious concerns were raised about the gross abuse of the right to a fair hearing.

Seeing the 1975/78 Military regime staged their coup on the allegation of corruption, there was a patent bias, an obsessive compulsion to find a smoking gun even when it was from a bygone colonial era. Improper prosecutorial, ultra vires, and oppressive conduct was evident. An impartial tribunal was not to be expected.

Section 6 of Decree 37, 1968, provides that no punitive recommendation shall be made by the Military Tribunal “provided that before making recommendations affecting any person under this subsection, such person shall have been given an opportunity by the tribunal, of being heard”. There is no evidence that Chief Anthony Enahoro was given the opportunity to be heard before properties he acquired from 1956 were supposedly “forfeited” by military order. The prospects of an effective legal redress while he was alive and even after his death came to only the instrumentality of a pardon what with the ousting of the jurisdiction of the courts as regards historical military injustice, the long passage of time, compounded by political victimisation for pro-democracy activism which impelled Chief Enahoro, to go into exile in England.

President Buhari exercising Perorogative of Mercy

The Prerogative of Mercy

The prerogative of mercy successfully invoked in the late Chief Enahoro’s matter is an integral part of the legal system and it exists to protect citizens against possible miscarriage of justice. There should not be any hesitation to recommend the exercise of that power if there are substantial grounds for believing that a miscarriage of justice may have occurred for which there is no remedy in the courts.

In summary, other para-legal and persuasive issues were tendered to President Buhari for consideration, including the argument of the late Chief Obafemi Awolowo, whose 28th March 1966 pleading for clemency was remarkably relevant half a century later, he asserted;

That, “the final phase in the struggle for Nigeria’s independence was initiated by my Party in the historic Self-Government motion moved by Chief Anthony Enahoro and supported by me on 31st March, 1953. IT SHOULD BE REGARDED AS MORE THAN IRONICAL, AND AS PALPABLY TRAGIC, THAT TWO OF THE ARCHITECTS OF THAT INDEPENDENCE AND, INDEED, THE PACE-SETTERS AND ACCELERATORS OF ITS FINAL PHASE SHOULD BE UNFREE IN A FREE NIGERIA.”

The implication of the Presidential pardon or prerogative of mercy granted a citizen is to wipe out not only the sentence or penalty but the conviction and all its consequences and, from the time it is granted, leaves the person pardoned in exactly the same position as if he had never been convicted. The powers of the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria to grant pardon are derived from s. 175 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (as amended). It is clear from S. 175(2) of the Constitution that the powers conferred, on the President under subsection (1) of the section shall be exercised by him after consultation with the Council of State. However, under S.175(3) as regards persons convicted or sentenced by a Court Marshal, the powers of the President and the Commander in Chief to review the matter and consult with the Council of State is not circumscribed, and the requirement of consultation is not mandatory. Chief Enahoro was indicted by a Military Tribunal, and wrongfully punished by the Supreme Military Council, which is like a Court Marshal. Since the President is not bound by any advice proffered by the Council, as regards Court Martials, the decision to grant or refuse an application for presidential pardon remains ultimately that of the President. And as in this case, the discretion was wisely exercised to Chief Enahoro’s favour, upon the recommendation of the Presidential Advisory Committee on the Prerogative of Mercy.

Secondly, the President may grant pardon only to persons either “concerned with or convicted of an offence” created by an Act of the National Assembly. The phrase ‘concerned with” … within the contemplation of S. 175(1)(a) of the 1999 Constitution implies that the President may exercise the powers conferred on him under the provisions in favour of a person who has not been convicted of an offence but was involved in or implicated in the commission of that offence. Or as in the case of Chief Enahoro, was alleged to have committed an offence but was not convicted. Thus, prior conviction for an offence created by an Act of the National Assembly is not necessarily a sine qua non for the grant of pardon, even though that’s the prevailing legal thought. It is sufficient if the person pardoned was merely involved or implicated in the commission of the offence in question although no trial or conviction has taken place.

Furthermore, while technically you cannot pardon a man for something he has not done, someone can be “pardoned” under S.175 of the Nigerian Constitution, for an offence in which s/he was implicated in, but was not convicted. Also you can be “pardoned” in a situation where a miscarriage of justice can be established and there is no available legal remedy as in the case of Chief Enahoro. In other jurisdictions, concepts like, pardon, redress, remission, rescission, commutation, grace, mercy, exoneration, exculpation, droit de grace, Weideraufnahme, and a variety of others are called in aid to rescue the victims of the law’s imperfections.

It is submitted that while mercy remains the primary ground for the exercise of the pardoning powers, the validity of a pardon cannot be vitiated on the ground that it was motivated by considerations other than mercy. In other words, apart from mercy, the grant of pardon has been justified on other grounds. There is authority for the view that pardon can be utilised as an instrument of equity ‘in criminal laws, a means of preventing injustice and ensuring fairness for those wrongly convicted or harshly sentenced.’

In most legal jurisdictions, pardon has never been codified into rigid rules. Rather, its function has been to break protocols and conventions. The increasing sophistication of the rules of evidence, with DNA, other forensic methods, among others, has enriched the jurisprudence of the prerogative of mercy. This largely explains why posthumous pardons are becoming widely acceptable as fresh evidence are clinically unearthed and adduced. Pardon has therefore become a safety valve, like doctrine of equity, by which harsh, unjust, or unpopular result of formal rules can be redressed.

A much younger Enahoro

In the plea for prerogative of mercy and compensation, which was initially presented to President Goodluck, and later to President Buhari, it was argued, pardon would be one of the finest tributes to the memory of the late Chief Enahoro, which the Federal Government has promised to recognize, accord due accolade and memorialize. The presidential pardon will expunge the unwarranted stigma on the impeccable public record and legacy of struggle against colonialism, for democracy and good governance of Chief Enahoro. It will also rehabilitate the family fortune that has been so devastated as a consequence. In a sense, the plea was partly founded on humanitarian grounds, appealing to the President to exercise his enormous discretion favourably. As it is a patriotic call to bear true allegiance to that hallowed verse, of our National Anthem, that “the labour of our heroes past shall not be in vain”.

Among other para-legal issues are the indefatigable lobbying efforts of Dr Philip Idaewor, Mr Rowland Ataguba, Prince Goddy Jedy Agba and Mr Gabriel Enahoro who kept faith in the ultimate victory of good over evil. They continued to believe, that though politics is fraught with skullduggery, it nevertheless, presents limitless opportunity to promote social justice.

Finally, President Buhari demonstrated soothing graciousness, decisive progressive leadership and sound judgment, to review an unjust decree of 1977 Supreme Military Council. It is a landmark declaration with far reaching impact on our national, political and legal history. With the restitution following this pardon, Chief Anthony Enahoro CFR can now fully rest in peace.

Conclusion

Interestingly, this grant of presidential pardon, would make Chief Enahoro arguably the first person in the world to have received two presidential pardons. One in his lifetime, given by General Yakubu Gowon who granted pardon in August 1966 to Chief Anthony Enahoro and others convicted and jailed on 11th September 1963 for Treasonable Felony. And the second pardon by President Buhari, granted to Chief Enahoro, posthumously.

The tragic paradox of one of the foremost campaigner of Nigeria’s independence being wrongfully stigmatized with an unfounded allegation, and having all his valuable assets and properties confiscated in an independent Nigeria was not lost on President Buhari. The UK Times of 4th January 2011, in their tribute to Chief Enahoro, noted, thus:“For seven decades he played a prominent role in the tumultuous politics of the country, campaigning first for independence from Britain, and later taking a courageous stand against some of Nigeria’s most brutal dictators. “He was imprisoned several times, both before and after independence. But he remained largely untainted by allegations of impropriety despite spending so many years in one of the world’s most corrupt political systems.