As long as the framing of the African crisis is what will tie together the three other forms of power to be mobilised for continental emancipation, so long will the loss of any of the analytically well heeled, bold and vocal African scholars be mourned for as long as possible. This is precisely what is happening to the late Professor Thandika Mkandawire who passed on March 27th, 2020.

A number of African and non-African scholars have taken turn to pay tribute to the late Malawian, a few of which were published in Intervention, (https://intervention.ng/19739/; https://intervention.ng/19751/). But a particular tribute was still missing. That is the tribute from the other African scholar who worked with Prof Mkandawire for eleven long years – Dr. Yusuf Bangura. With so much to say, his tribute is an 8,643 word affair. Permitted to publish the tribute, Intervention is breaking it into two parts for readability consideration even as revealing and very interesting as it is.

The author

By Yusuf Bangura, (Nyon, Switzerland, Bangura.ym@gmail.com)

The news of Thandika’s passing on 27 March came as a big shock, even though I knew he was unwell in the last few years. His casual but forceful personality and unbounded energy made me believe that the laws of nature might not easily apply to him. He always seemed to bounce back from adversity with renewed vigour and focus.

He survived two cancers in 2004 and 2009 when he was at the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD), but continued to work diligently, giving inspiring lectures around the world, writing brilliant academic papers, and generating insightful and provocative ideas. Always sharp, witty and booming with insights, I felt he would survive the third attack, which, sadly, turned out to be fatal.

Even when, a year ago, he was undergoing a difficult treatment for his illness, he wanted us to co-organise a Summer Institute Programme at the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) on the transfer of power in Africa’s fledgling democracies.

Thinking seriously and passionately about development, especially as it relates to Africa, was the defining feature of Thandika’s scholarship. He was the quintessential iconoclast–restless, uncompromising and acting like a laser beam when discussing development and challenging conventional ideas.

For Thandika, dealing with development was like being confronted with ‘the fierce urgency of now’, to borrow one of Martin Luther King’s famous expressions; or, as Thandika himself expressed it, drawing on the late Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere’s insight on the subject, Africans ‘must run, while others walk’. It is difficult to think of a scholar who is as driven as Thandika was on the imperative of promoting development in Africa. He was never tired of urging likeminded friends and colleagues not to relent on the development project and to combat dominant, but dodgy frameworks and perspectives.

Thandika was solidly rooted in African research and social networks and had numerous friends around the world, as well as a healthy and critical global outlook. He was a voracious reader; had the rare gift of thinking quickly and clearly on his feet; kept a huge library, a part of which he carried around in a USB stick; and had an amazing ability to frame issues in refreshing ways.

Because of his pioneering work in developing social science research in Africa during his leadership of CODESRIA, he became a household name in research communities in virtually all African countries. Young scholars saw him as their mentor. One beneficiary of his research capacity building programme at CODESRIA, the Nigerian political scientist, Jibrin Ibrahim, recently coined the term ‘CODESRIA Brought Ups’ to describe those who were initiated into the world of cross-national research at CODESRIA.

Thandika’s eleven years as Director of UNRISD (1998-2009) and ten and half years as Professor of African development at the London School of Economics and Political Science (2009-2020) broadened his reach and vision beyond Africa. He became a globally-recognised scholar for his writings on the harmful effects of structural adjustment programmes, the possibility of crafting developmental states in Africa, and theorising the transformative role of social policy. He was also respected for his systematic critique and demolition of conventional, neopatrimonial ideas of the African state.

Thandika’s worldview can be traced to three sources. The first was the oppressive and racist nature of the colonial enterprise. Born in Zimbabwe (Southern Rhodesia) to a Zimbabwean mother, and having grown up in Zambia (Northern Rhodesia) and Malawi (Nyasaland), his paternal home, he had a mature and informed understanding of the twin evils of colonial domination and racial discrimination before embarking on university studies in the US. Recounting his experience in Zambia, where his father worked as a tailor in the copper mines, he observed that ‘mine schools were designed to produce semi-educated mine workers’ (Kate Meagher, ‘Reflections of an Engaged Economist: An Interview with Thandika Mkandawire’, Development and Change, Vol. 50, No.2 March, 2019; p.513).

When Thandika relocated from Zambia to Malawi to continue his education, he was shocked to see that Africans were employed as train drivers—high status jobs that were reserved for whites in Zambia, which had a strictly enforced apartheid labour market regime. As a secondary school student and later journalist, he was active in Malawi’s anti-colonial struggles. The colonial government arrested him at the age of 21 and six of his colleagues on allegations of ‘sedition and inciting violence’. They spent three months in prison breaking stones. The colonial encounter transformed him into a fierce nationalist, pan-Africanist and anti-imperialist.

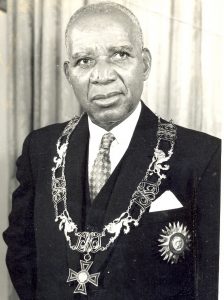

The late Dr Kamuzu Banda of Malawi

The second influence on his worldview was his early realisation that independence did not necessarily mean freedom from despotism. His Malawian passport was revoked in 1965 by the new Kumuzu Banda government after a ‘Cabinet Crisis’ in which the radical wing of the nationalist movement, with which Thandika identified, were driven out of the seat of power. He had written an article that was critical of the governing party’s youth wing’s attack on Malawi’s new university. Banda was offended by the article and called him a ‘yelping intellectual yuppy’ that he wanted ‘alive if possible, dead if necessary’ (Meagher, ibid, pp. 532). The revocation of his passport cost him 30 years of exile; he could only see his parents in Zimbabwe after 20 years when he was invited to help establish Zimbabwe’s Institute of Development Studies. Banda’s despotism instilled in Thandika a visceral hatred for authoritarian rule and belief in the need to ground development in democratic processes.

The third influence was the social democratic character of the Swedish state, which granted him asylum and citizenship, as well as an opportunity to further his studies and teach in one of its universities. He was impressed by the effective way the Swedish state managed its economy, as well as its redistributive policies and social reforms that produced highly egalitarian outcomes—all achieved without sacrificing democratic principles and processes. In his words, ‘Sweden made one aware of the ways in which ‘embedded liberalism’ could tame the structural power of capital’ (Meagher, ibid, p. 519).

Thandika was a prolific writer—his writings exploded exponentially during his twenty one years at UNRISD and LSE. He wrote on a wide-range of issues—on macro-level economic development, structural adjustment programmes, economic policy making, institutions and development, agriculture, industry, the state, social policy, democracy, conflict, nationalism, pan-Africanism, ethnicity, academic freedom, culture and African intellectuals. He also occasionally forayed into literature to illustrate his arguments. He had an opinion–often controversial–on almost every subject in the social sciences and public policy.

It is impossible to address all of Thandika’s work in this tribute. In thinking about him as a colleague and friend, I discuss instead some of his major contributions in the study of development. I start by examining his understanding of development, which was at the heart of his scholarship. I then discuss his key works under four themes: combatting Africa’s maladjustment; developmental states and neopatrimonialism; advancing the development agenda in social policy; and grounding development in democratic processes. In the last three sections, I discuss his role as an institution-builder in social science research, focusing on his leadership in CODESRIA; his ‘outsider’ status in the UN, which covers his tenure at UNRISD; and my personal relations with him.

The primacy of development

For Thandika, development was the filter or primary lens for assessing public policies and the human condition. His training in economics in the 1960s, when development economics was fashionable, and exposure to the classics in economic history and radical political economy were the building blocks for his conceptualisation of development. Development economics emerged in the 1940s and 1950s, enjoyed much respectability in the 1960s and 1970s, but was eclipsed in the 1980s by neliberalism. Development economists focused on how late industrialising or poor countries could catch up or bridge the development gap with countries that were already industrialised.

As Thandika observed in summarising the key ideas of this branch of economics in his paper for an UNRISD-IDEAS conference on ‘Rethinking Development Economics’ in 2001, late industrialisation requires a ‘big push or critical minimum effort or a great spurt to turn the process of cumulative causation into a virtuous cycle of positive feedback’. The aim is to aggressively move countries from ‘a low equilibrium trap’ or ‘vicious circle of poverty’ that history, or in the case of Africa, colonialism, bequeathed them, towards a state of high equilibrium or self-sustained growth rates and transformation.

Some of the influential development economists that Thandika was attracted to were Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, Harvey Leibeinstein, Gunnar Myrdal, Francois Perroux, Arthur Lewis, Albert Hirschman and Alexander Gershenkron. Gershenkron’s Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective (1962), which Thandika often cited, had a strong impact on his ideas on catch up and structural change. To Gershenkron, late industrialising countries can leapfrog or skip stages traversed by developed countries by learning from prior mistakes. Countries that take catch up seriously are expected to have high growth spurts and rapid rates of industrial growth, will prioritise capital goods over consumer goods, and the state and big banks will play an active role in driving development.

The frame game

The key lessons Thandika drew from this literature were that development represents: i) sustained levels of high growth, structural change and economic diversification; ii) qualitative improvements in wellbeing, especially for those in the lower scales of the income or social ladder; and iii), improvements in social relations and institutions.

In his inaugural lecture at the LSE, which he titled ‘Running While Others Walk: Knowledge and the Challenge of Africa’s Development’ (2010), he argued that as a ‘late, late, late’ industrialising continent, Africa should study the paths traversed not only by the front-runners of industrialisation but the development experiences in every part of the world. In this regard, leap-frogging in development calls for ‘levels of education and learning that are far higher than those attained by the pioneers at similar levels of economic development’ (p. 18).

Thandika’s commitment to economic and social change made him reject the neoliberal turn in economics, which emphasised the importance of getting prices right, deregulation of economies, public expenditure cuts and dismantling of development planning institutions. Under neoliberalism, economics became a study of macro-economic stabilisation and trade liberalisation. Indeed, neoliberalism and the multilateral financial agencies’ capture of Africa’s policy space negated everything he learned in development economics; it challenged his dream of rapid industrialisation and fierce sense of nationalism and anti-imperialist beliefs. In his insightful interview for Development and Change in 2019, he singled out development as the unfinished business in Africa. In his words, ‘pretty much every big dream I had about Africa, except for development, has come true’ (Meagher, opp cit. pp. 540).

Thandika was also critical of development approaches that largely seek to manage poverty. These include studies that celebrate incremental changes in the lives of the poor, such as the literature on coping strategies of informal low-skilled individuals; micro-credit programmes that barely lift people above starvation income levels; and targeted handouts to the poor that fail to transform lives in meaningful ways. Where poverty is widespread, as he argued, it makes little sense to target the poor, as this may be administratively costly, may generate leakages, limit the poor to inferior services, and make it hard to build links or solidarity between the poor and better-off groups in financing and providing quality services. To him, low-value added informal income generating activities are an index of underdevelopment. While it is important to understand how the poor make a living, the goal of development should be to transform economies and the lives of the poor, not manage or glorify them.

He was also dissatisfied with the anti-growth positions of sections of the environment movement and much of the literature on environmental economics, which he believed does not pay sufficient attention to industrial catch up, including the need not only to transfer resources to poor countries as part of the much discussed climate change mitigation bargain, but also, and more importantly, to give poor countries policy space and tools to advance the industrialisation project. As he often argued, poor people will only be able to devise effective adaptation strategies to climate change and take the environment seriously and contribute universal mitigation targets when they have seen substantial improvements in their lives. Unfortunately, his writing on the environment was very thin. It would have been useful to know how strategies for industrial catch up would look like in the context of environmental sustainability, especially as Africa is likely to pay a much higher price than rich regions even though it is least responsible for the warming of the planet.

Combating Africa’s maladjustment

Thandika spent much of his time studying, analysing, debating and campaigning against the IMF and World Bank’s neoliberal adjustment programmes. Africa’s maladjustment, as he described the continent’s experience under adjustment, was the one issue that he consistently engaged with for over thirty years in his study of development. Whether at CODESRIA, UNRISD or LSE, he was obsessed with what the multilateral financial institutions were doing to Africa.

He read virtually everything the World Bank wrote on Africa and meticulously tracked the progression of that institution’s adjustment policies and programmes. He organised several conferences, wrote many articles in journals and edited books, and published in 1999, with Charles Soludo (an economist who later headed the Nigerian Central Bank), an influential two volume book, Our Continent, Our Future: African Perspectives on Structural Adjustment (1999); and African Voices on Structural Adjustment (2003). Our Continent, Our Future was a succinct, well-argued and evidence-backed synthesis of Africa’s adjustment experience in the 1980s and early-to-mid 1990s. Foreign Affairs (September/October 1999) described it as ‘a valuable primer on current development debates’.

The late Prof Thandika Mkandawire

Prof Charles Soludo

Thandika and Soludo made three important points in that study. First, they were among the first scholars to show that African countries were not the perennial failed states that the multilateral financial agencies and Africanist political scientists imagined them to be. In the logic of these agencies, the post-colonial African state was a captured, neopatrimonial institution that largely served coalitions of narrow urban interests. The multilateral agencies believed that these special interests extracted rents from Africa’s state-directed development, leading to price distortions, system-wide ineffiencies and economic backwardness. The historical record, however, was different. Thandkia and Soludo demonstrated that Africa’s annual GDP per capita growth between 1965 and 1974 was positive. At an average of 2.6%, it was much higher than the GDP per capita growth of the 1980s, which declined by 1.3% per annum, despite Africa receiving about ten years of neoliberal adjustment medicine. Some countries, such as Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya and Nigeria were, in fact, growth miracles before their economies were plunged into crisis.

Second, Thandika and Soludo demonstrated that the focus on domestic policy failures deflected attention from efforts by African states in building the foundations for industrial development; the big push in social development, especially in the field of education, which produced a cadre of quality professionals and administrators; and nation-building strategies in a continent that hosts the largest number of ethnic groups in the world. The preoccupation with domestic policy failures also meant that the role of external factors, such as the volatility of global commodity prices, was ignored. In the eyes of the multilateral agencies, if the crisis was caused by domestic policy failures, it was justified to apply shock therapy or the full burden of adjustment on African countries. This distorted reading of the problem caused a rift with African policy makers, who highlighted the significance of deteriorating terms of trade in explaining the crisis. It led to ruptures in policy dialogue and what the agencies liked to call policy slippage.

Third, Our Continent, Our Future provides a useful overview of the economics literature that tracked African countries’ performance under structural adjustment, and the numerous, but often contradictory and ultimately failed efforts by the World Bank to present the adjustment programmes as successful. While there were positive results in macroeconomic stabilisation, the record on economic growth, industrialisation, agricultural performance, foreign investment flows, domestic resource mobilisation and poverty alleviation was shockingly poor. Many countries that the World Bank classified as success stories, including so-called strong adjusters, often found themselves downgraded as non-adjusters within very short periods. The lesson was unmistakable: the adjustment programmes were largely about macroeconomic stabilisation; they failed to address issues of growth, structural change and the well-being of the poor.

By the mid-1990s, it was obvious to most observers that adjustment was not working. There were strong calls, therefore, for a change of direction. The reform package that emerged added issues of growth, participatory policy making, national ownership of policies, poverty reduction strategies, governance reform and institutions, but did not dilute the fundamental demands for stabilisation, liberalisation and privatisation.

Faced with the stark reality of Africa’s poor economic performance and pressures for change, the World Bank was forced to acknowledge many of the policy failures of adjustment but failed to change the way it engaged African economies. Thandika meticulously tracked these acknowledgments of failure, which he called mea culpas. When he was at UNRISD, he was my primary source for keeping abreast of the World Bank’s policy gymnastics, or mea culpas. He published four useful papers on these policy changes and the maladjustment of African economies (‘Maladjusted African Economies and Globalisation’, Africa Development, Vol. XXX, Nos. 1 and 2, 2005; ‘Institutional Monocropping and Monotasking in Africa’, in A. Norman et al (eds.), Good Growth and Governance in Africa: Rethinking Development Strategies, 2011; ‘Can Africa Turn from Recovery to Development?’, Current History, May 2014; and ‘Globalisation and Africa’s Unfinished Agenda’, Macelester International, Vol. 7, Spring, 1999).

When African economies experienced growth spurts in the late 1990s and 2000s, the multilateral financial agencies quickly forgot about the mea culpas and, as Thandika observed, touted the recovery as a delayed outcome of the structural adjustment programmes. However, the recovery has failed to transform African economies and average per capita incomes are still lower than in the 1970s. As he put it, ‘if you have that many mea culpas, you create an economy, and that economy behaves in a particular way’ (Meagher, 2019, p. 522). Understanding the type of African economies that have emerged after more than 30 years of structural adjustment and the World Bank’s large number of mea culpas was one of the two issues he was working on as book projects before his illness. One hopes that CODESRIA will collaborate with his family to finalise and publish these books, which should be a treasure in the study of African development.