Discourse and Conflict in Onugbo Ml’Oko, the Classic on the Idoma Universe

By Adagbo Onoja

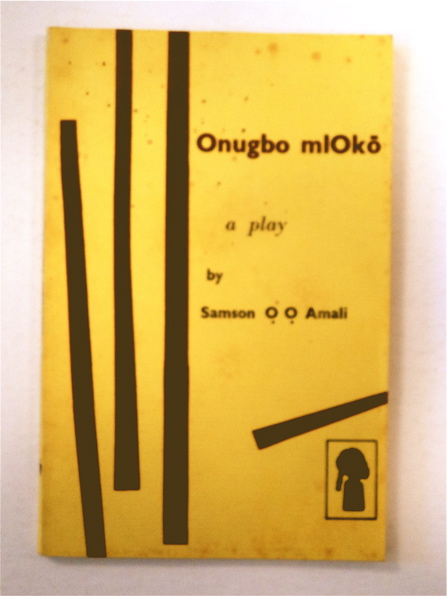

Prof Samshudeen Amali, author of Onugbo Ml’Oko

What might a fictional depiction of 20th century rural Idoma have to offer conflict analysis in 21st century mega-Nigeria? What a redundant question if the text is already called a classic, meaning that it has on offer an overpowering menu prepared from the knowledge warrant of ethnographic completeness. That is besides the ‘intertextual turn’ that insists on connecting every text to its textual ancestors in the meaning-making process. Thus shorn of the baggage of the single story, credit to Chimamanda Adichie, such a text can speak to anything as much as a piece written yesterday. It does this even better in the hands of critics who successfully resist the temptation to reduce the message of Onugbo Ml’Oko to that of the strange behaviour of Onugbo shooting Oko, his junior brother in the course of a hunting expedition because fortune favoured Oko whose exploits in the art of hunting overwhelmed Onugbo to envy and loss of capacity for discretion. Up to the time the expedition was winding down, Onugbo had killed nothing while Oko had killed antelopes, fourteen leopards and an elephant he compared to a mountain in size. At each stage of his feat, he called his senior to acknowledge and bless his prowess but only to get a cold shudder. He noted sadly to himself how “the heart of Onugbo, my brother is blazing red-hot like fire”. Onugbo subsequently blasted Oko to death on the pretext that Oko had muddled the pond and he could not quench his great thirst notwithstanding Oko’s denial of complicity. Of course, shooting Oko was no accident. He had it all worked out by saying at the end of a long soliloquy: “We are hunting. A hunting accident is what it is. It is done”.

Idoma in the Nigerian space

It is not impossible but very unlikely to find an Idoma lad for whom Onugbo Ml’Oko narrative was not part of his growing up down to the late 1970s. It was popular and interesting because of what an Idoma elder recently described as the charged emotional and sentimental imagery throughout the narrative. The obvious communal induction about it sank easily, leaving the absurdity of a brother shooting his brother well ingrained in the make-up of most members of post independence Idoma generation. It is a challengeable claim but certain to be the origin of the celebrated innocence or naivety and over-gratefulness of the average Idoma who might unconsciously be acting out that induction. After all, not a few referred to this when Chief Audu Ogbeh attributed to naiveté his attempt to speak truth to power against the crisis developing at that time in Anambra State and for which he ran into terminal trouble as National Chairman of the PDP.

So, central to Onugbo Ml’Oko narrative is violence that sprang from envy, greed, hatred and treachery. But, where did the envy and other similar attributes come from? After all, the story did not begin from the anti-climax in brother shooting brother to death. Rather, it started with ‘natural’ or brotherly love, two brothers who did not go without each other before the disaster. It is, in that sense, comparable to the rupture between Abraham and Lot or Cain and Abel, all as narrated in the Bible. In that case, how do we explain the good side of human nature that existed in the relationship prior to the conflict? Isn’t there something inadequate in allocating too much to human nature in explaining the violence? The evidence from Onugbo is about Oko having usurped his place and having deprived him of his worth. Onugbo was looking at it from the point of view of prestige, status and worth, none of which can be objectively located but his own cognitive sense of Oko’s feat. Language or language use was constituting the facts of Oko’s elephant and many animals into a different reality based on subjective evaluation. It points at the wager that meaning is contingent rather than objective or universal. In other words, Onugbo’s construction of Oko’s success as decentering of his worth prompted his action. For, if meaning is specific, which is the same as saying that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, then Onugbo’s envy is only a product of a truth peculiar to his standpoint. That is the standpoint from which he could only see the shadow of his junior becoming greater than himself, a standpoint provoked into being by the powerful, negative and destructive impulse envy aroused in him. Although Onugbo was to discover that Oko’s claim that he had no hand in dirtying the pond was true, it was too late. Suspicion and anger had so powerfully predisposed him to looking for the smallest evidence to get rid of Oko without the benefit of fairness or good judgment expected of him as the leader.

What this does is to force a recognition of how fundamental an aspect of human life such attributes as envy are but without forgetting to add that they are not natural but contextually activated. Here, it was activated as to undo the ‘natural’ or brotherly love in Onugbo and Oko’s relationship. The text tells us that, suspicious of Onugbo’s temperamental constitution, both parents drew his attention to his obligation to care for Oko. They did so at their respective points of death. There is thus a hint about Onugbo’s character that links him to a variant of what has passed into Nigerian English as the original bad boy. However, the text also reminds us how, in obvious deference to the parental reminders, Onugbo took time to train Oko to be a precision hunter. He only found himself regretting this once Oko’s professionalism superseded his. There is then a take away in how good and bad aspects of ‘human nature’ could come up, depending on what is at stake, meaning that he did not shoot Oko on account of being an original bad boy.

What this does is to force a recognition of how fundamental an aspect of human life such attributes as envy are but without forgetting to add that they are not natural but contextually activated. Here, it was activated as to undo the ‘natural’ or brotherly love in Onugbo and Oko’s relationship. The text tells us that, suspicious of Onugbo’s temperamental constitution, both parents drew his attention to his obligation to care for Oko. They did so at their respective points of death. There is thus a hint about Onugbo’s character that links him to a variant of what has passed into Nigerian English as the original bad boy. However, the text also reminds us how, in obvious deference to the parental reminders, Onugbo took time to train Oko to be a precision hunter. He only found himself regretting this once Oko’s professionalism superseded his. There is then a take away in how good and bad aspects of ‘human nature’ could come up, depending on what is at stake, meaning that he did not shoot Oko on account of being an original bad boy.

Against this background, it is possible to say that human nature or its manifestation in egotism, selfishness, greed or nastiness did not, in themselves, explain Onugbo’s behaviour or any conflict. what does was Onugbo’s discourse of the competition with his brother in the context of prestige, fame and self-worth in the Idoma universe at the time. The argument could be intertextualised to how the failure to grasp this ruined a similar reading of International Relations in terms of human nature. Hans Morgenthau and his fellow travellers were saying that nation states would continue to be nasty to each other because human beings who run these states are, by nature, nasty and egotistical, always concerned with power and prestige over the other. His critics simply said but it is the same selfish, nasty human beings who are also behind great humane accomplishments such as Penicillin, electricity, the aeroplane, among others. That shouldn’t have happened if human nature were static qualities. Onugbo Ml’Oko may thus be understood as a contribution to the critique of the naturalist narrative of social reality but from the specificity of the Idoma cultural universe by Professor Shamsudeen Amali, the author and one of its most sensitive observers.

Without deliberately privileging an author-centric reading, it should be noted how Amali fictionalised the Idoma universe in Onugbo Ml’Oko from the philosophical wager that reality is constructed and that meaning is specific, not universal in a drama text published as early as 1972 under the Bi-Lingual Literary Works series of the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ibadan when Amali was just a Junior Research Fellow. That was Forty-Five years ago. Since then, Amali has been here and there, from an Idoma who could work with an American in the academic enterprise of exploring the Idoma universe, both taking off from the University of Ibadan, before he branched off to the University of Wisconsin in the United States, then back to the University of Jos, becoming the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Ilorin and Nasarawa State University, Keffi in quick succession before ending up now as an elder academic.

The American under reference is the late Professor Robert Armstrong, the academic authority on what later became the Idomoid language family who retired to live at Otukpo till his death and the burial with full ancestral honours. It was not surprising he was conferred with the traditional title of ‘Oodejo’ of Idomaland. He assisted Amali to translate the work into English because Amali wrote the play first in original Idoma language, the point in doing so being to reduce the degree of loss of meaning inherent in translating from one language to the other. By original Idoma language is meant a distinction between Idoma language-use in those days and the slangy stuff of nowadays around Otukpo, Ugbokolo, Otukpa, Adoka, Ochekwu, Igumale and other emerging urban centres in Idomaland now.

The American under reference is the late Professor Robert Armstrong, the academic authority on what later became the Idomoid language family who retired to live at Otukpo till his death and the burial with full ancestral honours. It was not surprising he was conferred with the traditional title of ‘Oodejo’ of Idomaland. He assisted Amali to translate the work into English because Amali wrote the play first in original Idoma language, the point in doing so being to reduce the degree of loss of meaning inherent in translating from one language to the other. By original Idoma language is meant a distinction between Idoma language-use in those days and the slangy stuff of nowadays around Otukpo, Ugbokolo, Otukpa, Adoka, Ochekwu, Igumale and other emerging urban centres in Idomaland now.

The framework of discourse in relation to conflict analysis in this text can be seen in one more key theme. That is the communal or traditional trial system and its elaborate techniques, protocol and great communication for producing judicial truth. It is the inquest and the performance of it. But, just as those who emphasise the rupture in Onugbo and Oko’s relationship might only be comparable to the people in the story about unravelling the elephant, so also might those who might take the majesty of the inquest in an isolated sense. This legal process is not only a sequel to something to which it responds, it is equally a closely knitted and guarded process. Central to it is an involving pastoral concern with the individual in the process, with particular reference to the preservation of the wrong doer rather than his or her extraordinary dehumanisation that typifies the judicial system of the modern state. At last, it was the pain of regret for the evil he committed that was the greater punishment for Onugbo by Onugbo who is still in the bush in search of Oko, another instance of specificity and contingency of meaning. It is that specificity of meaning that makes hate speech, for instance, such a dreaded terrain in conflict management, particularly in a deeply divided society where power is balanced between the different camps as in Nigeria: class, regional, gender, ethnic, religious, generational and geopolitical terms. There are those who might, therefore, read the text and/or the author as serving a warning note on 21st century Nigeria with a 20th century art work. It is a warning warranted because the society today has too many Onugbos.

On the whole, this text thus speaks to conflict analysis not only in the diffuseness or fluidity of meaning in relation to the problematic of human nature but also in explaining how it connects to hate speech in the Nigerian crisis today; to the pitfalls of a psycho-dynamic notion of inter-state relations and foreign policy and, finally, to the message for Nigeria’s judicial establishment and the state on pastoral primacy in justice delivery.

Akey source of oral repertoire on the Idoma universe

Shouldn’t a text with much to pass onto everyone and even the future as this be reproduced for mass consumption? For, what seems obvious is how the survival of numerically small cultural groups such as the Idoma is tied not just to their collective self-imagination but, more importantly, their construction and projection of the identity. That makes Onugbo Ml’Oko a strategic starting point in terms of protecting, preserving and transmitting Idoma written literature and language, especially the alphabets as recorded in this text, at a time the small ethnic groups are gravitating towards majority languages in order to understand each other but having to do so at a time the UNESCO alarm on dying languages is also ringing ceaselessly.

Of course, there will arise the question of who makes it happen, most especially moneywise. A plausible pathway is an emergency conclave of the leading lights of the artistic and discourse flow in Idomaland – the 2Face Idibias; the Bongos Ikwues; the Dr. Paul Enenches; the Professor Armstrong Adejos; the Professor Isawa Elaigwus – coming together to think about and explore its accomplishment. It is doubtful that anyone would object to them seeking the answer in meeting the David Marks, the Mike Onojas, Steven Lawanis and all such Idoma sons and daughters who can help mobilise funds. Or, carrying a grand begging bowel towards the Aliko Dangotes, Mike Adenugas and General T. Y Danjumas of Nigeria invoking corporate social responsibility! General T. Y Danjuma would be particularly significant on this list, being a hybrid of community, civil society, regional, business and nation building leadership. Being the grand custodian of the Idoma universe, the Och’Idoma of Idoma automatically brings up the list, providing the royal blessing for all cheerful givers. The radius of those to be ‘begged’ could be unlimited. What would count might be what works. And what works should be to see Onugbo Ml’Oko on celluloid, coherently narrated and technically well produced.