Nigeria’s Welcome But Surprising Recovery Plan

It is more than an economic strategy because there is almost no subject matter about Nigeria that is either not mentioned or implied. To that extent, the Economic Recovery and Growth Plan (ERGP), 2017 – 2020, the APC led Federal Government has finally come out with is more of its discourse of Nigeria than anything else. A discourse perspective would be most helpful way of unpacking it by bringing out the binaries grounding it, the imageries invoked, the ‘truth’ that is privileged and the ‘truth’ denied, the gods called upon to bless the document and those not invited, etc.

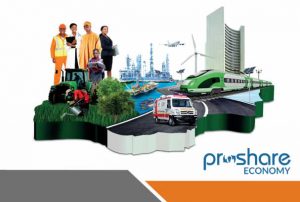

It would not be surprising if a debate arises over the document as to what it actually is: the FG’s programme or the construction of a national vision. There is a mixture of both in the document but it looks more like what the constellation of the elite in power now would like to see and be able to do by the end of its first term. The periodisation, 2017 – 2020 suggests this. The very interesting graphics with which the document opens speaks to a rather ambitious or transformative vision. There is a bullet train, a giant building, all signifying a more modern and functional economy. Agriculture is located in the front in that graphic while oil is now at the back, expressing the desire to shift from extreme oil dependency. Energy diversification is also there what with the wind fan and solar panel. Then there is the line up of professionals at the back that will provide technical expertise to underpin the modern economy.

It would not be surprising if a debate arises over the document as to what it actually is: the FG’s programme or the construction of a national vision. There is a mixture of both in the document but it looks more like what the constellation of the elite in power now would like to see and be able to do by the end of its first term. The periodisation, 2017 – 2020 suggests this. The very interesting graphics with which the document opens speaks to a rather ambitious or transformative vision. There is a bullet train, a giant building, all signifying a more modern and functional economy. Agriculture is located in the front in that graphic while oil is now at the back, expressing the desire to shift from extreme oil dependency. Energy diversification is also there what with the wind fan and solar panel. Then there is the line up of professionals at the back that will provide technical expertise to underpin the modern economy.

The graphics is its first shot at argumentation via a representational critique of the Nigerian economy described “dependent, consumption driven and undiversified” as to be only capable of a “positive but jobless growth”. By implication, growth that responds to employment is an adequate mark of progress for the ideologues of this document. Putting the contribution of manufacturing to exports at less than one per cent, it dismissed “the high growth rate of 2011 – 2015 which averaged 4.8 per cent per annum” by attributing it to high oil prices and being non-inclusive. It then formally and categorically declared the free market business model as the right way to go, saying the government approached philosophy of governance from “the understanding that the role of government in the 21st century must evolve from that of being an omnibus provider of citizens’s needs into a force for eliminating the bottlenecks that impede innovation and market-based bottlenecks”. This is the crux or the future they are imagining.

It could be said there is nothing more to read after coming across this sentence quoted above in the Executive Summary because the rest of the document is the interpretation of and arrangement of the facts and figures to produce the ‘truth’ that only a market based business model is the game in town. Still, it is only by reading the entire stuff that the reader comes across admissions such as the last but one paragraph on page 112 where it is hoping to awake the private sector from what it says is its weak position to actualise the ERGP through increased incentivisation of that sector. It thus pays to take the time to read the 140 page document. It is only by doing so that its supporters, critics and dissenters could more successfully determine the hopeful as well as its troubling dimensions.

One face of the Nigerian economy

Meanwhile, the document has an elaborate outlay of its own approaches. It puts implementation at the core. It is privileging certain ‘new initiatives’ such as taking oil production to 2.5 million barrels in daily production by 2020 by privatising selected assets and revamping local refineries; sorting out the environmental mess in the Niger Delta and, generally being able to diversify the economy. It is keen about creating more space for the entertainment and creative industries. It talks about building on sectoral strategies such as the National Industrial Revolution Plan and the Nigeria Integrated Infrastructure Plan. A Private-Public Partnership hybridization is interesting to it as much as the incorporation of the state governments into the framework. There is silence on what happens to state government that have more critical or different framework from the trajectory favoured by this. Could all these be called new approaches? Are they approaches or targets?

This document has not failed with respect to the joke that there must be an industry in every government concerned with just manufacturing phrases and concepts. There are emphatic references to phrases and concepts such as inclusive-growth vision; restoring economic growth; “leveraging the ingenuity and resilience of the Nigerian people” and the specific commitment of creating 15 million jobs, by which poverty would be reduced from 61 to between 50/55 per cent by 2020.

The other face of the Nigerian economy – the face of the many losers

Right away, some people would say that it is a problematic document. The first ground for such pessimism would be the question of how much of all these are doable between now and 2020. The document is only a rationalisation of what has been going on since 2015 but even then, 2019 is almost here. A second query would be whether the government accepts that Nigeria is basically an agrarian economy whose transformation into a modern one would require a push much more than a market based approach. In this regard, one cannot but think of Lee Kuan Yew’s reason for rejecting the market strategy: people are not equal in their abilities. He feared that the market will produce too few big winners, many medium winners but considerable number of losers and there will be so much tension in the society. This was the reason he rejected both capitalism and socialism. Nigeria has more reasons to be fearful of the market than Singapore at the time Yew arrived at his conclusion.

There is something curious about a plan whose overarching framework is the market based solution but in an economy in which there is no private sector. This is a point the paragraph on page 112 mentioned earlier on amounts to, hence the plan or is it hope of the government saddle itself with the additional burden of incentivising a private sector into life, what former President Obasanjo calls baby-sitting of capitalists by making it state’s duty to wean them. Would that not amount to subverting the cornerstone of a market model of business because it means the state is subsiding capital? Doesn’t that go against the conception of the state as an umbrella, a shield for everyone rather than for people pretending to be capitalists?

Although that is the current trend across the world, the fact is that it is also the explanation for much of the crisis, including wars, across the world because capitalists are relying too much on the state to fight its competition wars. That is more at the level of great powers but it should serve as a warning. Does it pay for the state to modify the law of risks and investment? Is it not better if capitalists in Nigeria take the risks associated with private enterprise so that they will come out well steeled to think, act and compete like their counterparts everywhere else? Voices have been heard contending that God has done half of that job for them in Nigeria by endowing the country too abundantly. The rest is for the government to send them forth to explore those bounties. And that government should worry about providing electricity and other items of infrastructure for the whole country. After that, let the capitalists sweat it out. It has happened in Nollywood and happened successfully. Where capitalists are still ill-equipped to go and these are still plenty in most African countries, let the state take such realms and play the investor. And make profit. In the oil and gas sector, most of the key players globally are state run outfits. And they are making profit.

The popular privately owned Nigerian airline

The continuing collapse of the airlines, banks and the virtual failure of concessioning does not position the private sector to be trusted to take the country to the next level. Perhaps, they are not to be blamed. Their counter-parts in the developed economies from the US to West Europe to emerging economies in Asia did not play any such roles at the time of becoming of those economies. The commanding heights of those economies were under state control. The private sector came in thereafter. That is what should also happen here because, as honestly admitted by the document, there is no private sector with any capacity to replace the Nigerian State from being the leading force for social transformation. The error in thinking otherwise is why African countries such as Ethiopia, Kenya, South Africa, Egypt and Ghana, to mention a few, are each successfully running national airlines profitably but not Nigeria.

There is a romanticisation of industrialisation in the whole document. Yet, without industrialisation, neither the expectations of the generality of Nigerians nor of the document will materialise. Yes, the document talks about increasing oil production and revamping local refineries but in the context of privatisation. That leaves observers wondering how the cost of energy won’t be so high, perhaps higher than they currently are. How would local producers compete with outsiders such as China even within ECOWAS sub-region in such circumstance? How would national interest in industrialisation not be compromised?

A private sector led economy in a country which is just thinking of beefing up such sector is an invitation to crisis in any country relying on solid and liquid minerals to develop but without state interventionism. This is the reality for every primary commodity producer such as Nigeria because it means such a country will remain incapable of processing and storing the minerals. As long as they cannot do that, they have lost out. That is the global dynamics at the moment. This ‘law’ extends to agriculture and water resources as well.

Prof Osinbajo: Being inducted or speaking truth to the ‘Merchants of Venice’ at Davos?

It is, nevertheless, a welcome document even as it raises the question of how the neo-liberals came to obviously plant themselves in the engine room of power as to make their discourse of the Nigerian society the government’s official position in spite of well known nationalists in this government. It will take time for the government to ever see the futility in an economy structurally located as Nigeria’s. Perhaps, it is that Nigeria is beyond the government in power as far as development strategy is concerned. Although the nationalists will win any such debate as they did recently at the National Assembly during the debate on whether or not to sell remaining national assets, is it not also time for the government to expand its cabinet to absorb some of Nigeria’s best from across the spectrum of economic models?