Cracking General Obasanjo’s Staying Power in Nigerian Politics

By Adagbo ONOJA

At a time when the sources of the subjective requirements for rebuilding Nigeria are still indeterminable, the consistency as well as the pointed nature of General Olusegun Obasanjo’s national presence begs for scrutiny. It is about time an attempt is made to crack the puzzle whereby someone who cannot be said to be blameless over Nigeria’s mess has retained the courage and dare to rebuke and remind the nation? What explains General Olusegun Obasanjo’s staying power in Nigerian politics? Is it the case that Nigeria doesn’t understand him or he doesn’t understand Nigeria?

Obasanjo stepping out into the arena as a pupil soldier-statesman, with Joe Garba, his late Foreign Affairs Minister in tow and Andrew Young, then US Representative at the UN on the left

Interestingly, the Obasanjo persona has always attracted scholarly curiosity. Professor Sam Oyovbaire once said that if he were still an active academic, he would have encouraged a doctoral candidate to study Obasanjo and he would have supervised him or her. It is a long time this reporter read that remark and why Oyovbaire said so is lost to time but implicit in that is a reckoning with Obasanjo or aspects of him as a puzzle. Those who might ask why Oyovbaire developed such curiosity may find that the late Ibrahim Tahir expressed basically the same wish as Oyovbaire. In his own case, he had already developed a hypothesis to test. Obasanjo, he said in an interview published by the now defunct The Comet a month or so before its transformation into The Nation mid 2006 that Obasanjo is a noble man who has been 419ned by politicians. And that he wished he were just coming out of Cambridge and had the time to write Obasanjo’s biography himself so as to concretely pin down what drives Obasanjo. Professor Jonah Isawa Elaigwu, another frontline Political Scientist, has since joined the fray. In his own case, Obasanjo is not any puzzle at all but a study in “residual militarism and messianic arrogance”. Mvendaga Jibo, the Benue State University, Makurdi Professor of Political Science whose interview opened this newspaper late July 2016 described Obasanjo as someone who believes he must win all his wars.

Opinions such as these have led some people to argue that “the military in Obasanjo accounts for 70-80% of his character while other realms such as politics, self-writing and women compete for the remaining 20-30%”. There is no knowing how far Obasanjo would agree with this profile of him but the profile stretch beyond what academics say of him. Assuming, however, that (residual) militarism defines the essential Obasanjo, does that also account for his muscular national presence in Nigerian politics and the aggressive, daring instinct to remind or rebuke the nation as soon as he feels so?

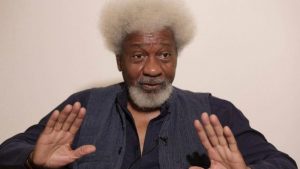

Wole Soyinka: Cracks Obasanjo as Obasanjo cracks him too

Two arguments are interesting in this respect. One is that posed by Professor Jibo that Obasanjo does not know as much as he claims to know. That tidies up with Elaigwu’s isolation of arrogance as Obasanjo’s driving force. For, if arrogance is proved against Obasanjo, then it suggests there is something he is hiding since arrogance masks a gap(s). And what is missing must then be a sensitive appreciation of Nigeria different from what Obasanjo has shown so far, even as he has ruled the country twice. The second is Yakubu Mohammed’s appraisal of Obasanjo in terms of TY Danjuma’s 2008 interview with The Guardian and in which TY dwelt a lot on the Obasanjo persona. Mohammed’s evidence needs to be taken at length: “A good starting point is General T Y Danjuma’s interview with The Guardian in which he dissected the man, his career, his command and his management of men and materials. Something that is obvious from that interview, though the general did not say it in many words, is that Obasanjo roundly outwitted them all – from the war front when he took over from the Benjamin Adekunle, the dreaded black scorpion, and broke the ranks of the Biafran military command to bring an end to the 33 months civil war, he outwitted them all the way to the highest office of the land , where he succeeded in the true fashion of Machiavelli, to decimate the ranks of those who paved the way for him to emerge from prison to presidency”, (Newswatch, March 3, 2008, page 5).

Fountain of controversy

Since the Machiavelli text implied is essentially a treatise in statecraft, Mohammed can be inferred to attribute Obasanjo-ness to a certain grasp of statecraft and its deployment as opposed to lack of sensitive appreciation of Nigeria. That is to say that there is an Obasanjo sensitivity to Nigeria which he operationalises, relying on residual militarism, messianic arrogance and a unique grasp and deployment of statecraft to deadly effect, time without number. And he does so in such a way non-traditional politicians such as Wole Soyinka, the Awujale as well as Obasanjo’s many other opponents and critics find it difficult to control and tame him. At least, not yet! Instead, he would appear to have tamed them to timidity, a thorough count of ‘them’ almost impossible because they stretch right from his family through his military colleagues, successors in power, his deputy, his aides, academics, institutions, world leaders, the media and fellow politicians. Only the most legendary ones can be cited to prove the title of this report as well as the sub-thesis of capacity for a deft combination of the three elements of residual militarism, messianic arrogance and grasp of statecraft or Machiavellianism.

He has just concluded a duel with the Awujale of Ijebuland in connection with a portion of the Oba’s autobiography. The point of contention is the Awujale’s narrative of a previous bout between Obasanjo and GSM bigwig, Mike Adenuga. He contests the Awujale’s representation of what happened but goes beyond that to infer an infraction on standard behaviour on the part of an Oba. Some other people would have responded to the alleged infraction with a gentle reminder to that effect. No! Not Obasanjo. He must win all his wars, the longest lasting of which might be the one between him and Atiku Abubakar, his former deputy as president of Nigeria from 1999 to 2007. It is stated that Atiku was among the first set of players who went to Obasanjo after his release from prison in the aftermath of Abacha. There is no confirmation of whether this informed Obasanjo’s dramatic preference for Atiku in the event of his emergence as the presidential candidate of the People’s Democratic Party, (PDP) early 1999. As Atiku himself told the story, Obasanjo had called him and put down what, from hindsight, was a blackbox: Turaki, will you obey me or words to that effect. Whereupon Turaki replied yes, because submission to Obasanjo, he said, was the instruction the late Shehu Yar’Adua left for his fellows. In Turaki’s account, he was then told to go and tell the late Chief Solomon Lar that he had been chosen as the Vice-Presidential candidate.

Everything about this account spelt trouble and trouble-making on the part of Obasanjo. For, in negotiating the PDP, the tendencies that came together had an idea of who was to be where and, certainly, they were not expecting a presidential candidate who was coming to pick his own deputy in a solo manner. The party picks the candidates. It is not picked for it by anyone, including its presidential candidate. Obasanjo changed that. He was to advance on that when he became president by declaring the president the leader of the party rather than the National Chairman, arguing that such is the case in the United States where he said the party gives way once election is over. He only suffered a setback in Alex Ekwueme, the Vice-President under Shehu Shagari in the Second Republic’s rejection of the offer of Senate President, Obasanjo’s own way of ‘compensating’ or ‘incorporating’ him into the ruling crust of the PDP. Whether his intention in making that offer to Ekwueme was noble or suspect remains unclear. Some voices in the PDP then felt that compensating Ekwueme was not the business of the presidential candidate but of the party.

A president and his vice

Anyway, Atiku’s selection by the candidate stood and the two could be said to have got on very well till about 2003. The rest is now history. Atiku only managed to remain the Vice-Presidential candidate in 2003 because he appeared to have successfully decentered the president from the most decisive circuit in the PDP power machine at the time – the governors. To the extent that they control independent budget and own the delegates, the governors can install whoever they want if they are united. Obasanjo ate the humble pie and with the deft improvisations of party leaders, particularly Audu Ogbeh, he got the second term, settled down and then faced Atiku. That face-off is still unfolding, with potentials for tragic unintended consequences at some point.

Meanwhile, Audu Ogbeh who is reliably understood to have saved him in the turbulence of the last years of the first term was soon to get stuck. In a flash of what he later called naivety, the Benue born chief wrote a letter to the president agonising over a number of things happening under presidential watch. Ordinarily, the content of the letter was something that two senior citizens could clobber themselves in a room without any aides and then put it behind them. That was not Obasanjo’s style once he read Audu Ogbeh to be playing an Atiku card in writing that letter to him. He made his move. Before Audu Ogbeh knew what was going on, he was out of office. The details of Ogbeh’s last days in the office as National Chairman of the PDP would only be known if he were to write his memoirs but threats and irresistible presidential intimidation have been speculated.

Audu Ogbeh’s predecessor had no less an interesting exit story. Barnabbas Gemade, an engineer who made a name as Managing Director of the Federal Government owned Benue Cement Company had been a player in the Abacha transition programme. In itself, that did not say much about his real stuff but it meant people were not expecting him to emerge a key player in the PDP which provided Obasanjo the platform to become the president. They were wrong. Obasanjo preferred him to the alternative, the late Sunday Awoniyi. In the end, Obasanjo prevailed and Gemade emerged the PDP National Chairman, replacing Chief Solomon Lar who had been the pioneer/caretaker chairperson, right from the process of negotiating the party to its formation. Solomon Lar was the one who took the letter by the G-34 warning Abacha to desist from self-succession. There can be no better case of taking oneself right into the lion’s den by Lar taking the letter to the Villa. His account of the tension that enveloped the period he was waiting to deliver the letter to Abacha in a Daily Sun interview is ever an inviting read. Lar put himself right in Abacha’s mouth. Surprisingly, Abacha did not munch him. He lived to tell the story, only to be eased out in not totally pleasantly.

Anyway, Gemade rode the tiger up to a point. Then Obasanjo called him one day and told him to name his compensation because it was time for him to leave as the National Chairman of the PDP. Gemade named his compensation and it was a done deal. However, a few days later, he was back to the president to say he no longer accepted the arrangement because he had seen a contrary vision. In the end, there was a test of strength and the result was a foregone conclusion: Gemade was the loser.

If we move the dateline from the party arena to his fellow Generals, the story is not different. Two are most legendary here – his duel with General Danjuma and IBB. In the case of Danjuma, the unsurpassable account through a self-reporting process is Danjuma’s February 2008 interview with The Guardian. A lot of water must have passed over and under the bridge since then and there might have been some fence mending between the two. But it remains the most intriguing that the two could become estranged, followed by quarrelling publicly. But while Obasanjo restrained himself from responding to Danjuma’s interview, that was not the case when IBB excoriated him. He responded in words that were least expected. That was before the war simmered. Another battle with another General worth recalling is Obasanjo’s contestation of Godwin Alabi-Isama’s account of the Nigerian Civil War in his book titled The Tragedy of Victory.

‘War without end’ might not be inappropriate encapsulation of Obasanjo’s engagements. When Zamfara State Government introduced Sharia in 1999, Obasanjo simply declared it as political Sharia which would fizzle out. The discourse took so much out of the whole fanfare. Interestingly, nobody replied him. How could anyone when most if not all the northern emirs, retired military and police personnel or civil servants had either worked with him or interacted closely with him and already had their back channel communication system with him? In 2004 in Jos, he told a pastor who was getting on his nerves, “CAN my foot’. It was to God’s glory that such came from a Christian president to another Christian. Otherwise, it would have had a different meaning and implications.

Asked by the defunct TSM to comment on Obasanjo’s suitability for the position of Secretary-General of the United Nations years back, the late Stanley Macebuh said that if Obasanjo got the job, he had to learn how to talk to people. Diplomacy, said Macebuh, is where professionalism demands finding silly ways of saying what one wanted to say. Obasanjo, he said, was the kind of person who, if he were the Secretary-General in the run up to the first Iraq war, could tell the US to stop being funny. Obasanjo did not become UN Secretary-General but be became Nigeria’s president again in his life time. And being Nigeria’s president is as involving as the UN job.

Hitting it off with Jimmy Carter as military Head of State in the mid 1970s

A case in point was the situation at the end of a three day state visit preceding the February 2002 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Australia when Obasanjo addressed a joint press conference with John Howard, the then Australian Prime Minister. What to do about Zimbabwe was in question, with Howard insisting on some immediate actions. At a point, he got Obasanjo infuriated. It showed when he spoke, by asking what Howard wanted. To insist on anything other than waiting for the then impending election in Zimbabwe, said Obasanjo, was akin to taking someone just sighted on the walkway to the jailhouse on the presumption that he had the features of people who committed such crimes. The international journalists who were not used to such rebuke looked taken aback. At the meeting with the Nigerians during that trip too, someone angered him and he showed it. Someone from the audience asked him why Igbos were being marginalised or something of that nature. He started with an attempt at providing a factual refutation of that claim. Half way, the stupidity of the question relative to what seemed to him to be the enormity of his evidence got him real angry. And that was the end of the interaction. So, Obasanjo fought not only at home. It is the same outside. And no group was excluded. He also took on academics and even his biographer.

Onukaba Adinoyi-Ojo was Airport Correspondent of The Guardian whose encounter with Obasanjo blossomed to where he ended up writing In the Eye of Time, a biography of Obasanjo. In time, Onukaba came to be part of the Obasanjo regime but only for the two to part ways, a fall out of the Obasanjo-Atiku conflict. As for academics, the protracted struggle against the sack of 100 academics at the University of Ilorin led them into collision with Obasanjo as president. This was aside main ASUU struggle for improved funding to which his responses were rarely friendly. The list could go on. It has still not touched on Obasanjo’s creases with players such as Nasir el-Rufai; Orji Uzor Kalu; Ghali Na’Abbah; Pius Anyim; Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala; Ken Nnamani; Ahmadu Ali; Tony Anennih and Aliyu Gusau have not been mentioned, for instance.

Onukaba Adinoyi-Ojo was Airport Correspondent of The Guardian whose encounter with Obasanjo blossomed to where he ended up writing In the Eye of Time, a biography of Obasanjo. In time, Onukaba came to be part of the Obasanjo regime but only for the two to part ways, a fall out of the Obasanjo-Atiku conflict. As for academics, the protracted struggle against the sack of 100 academics at the University of Ilorin led them into collision with Obasanjo as president. This was aside main ASUU struggle for improved funding to which his responses were rarely friendly. The list could go on. It has still not touched on Obasanjo’s creases with players such as Nasir el-Rufai; Orji Uzor Kalu; Ghali Na’Abbah; Pius Anyim; Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala; Ken Nnamani; Ahmadu Ali; Tony Anennih and Aliyu Gusau have not been mentioned, for instance.

But, even then, what the long list of people Obasanjo has fought in the last two decades or so does is to confer empirical support for the theory of an Obasanjo sensitivity to Nigeria with particular reference to residual militarism. All his wars with his others arise from his insistence on the superiority of his subjectivity/sensitivity to Nigeria and which he relies on militaristic tactics to push through. Although the tripod of residual militarism, messianic arrogance and deft statecraft by which the essential Obasanjo unfolds do not work separately, each one still comes into itself distinctly. From that point, it makes sense to take a distinct note of Obasanjo being the most tested godfather in Nigeria today.

One dimension of this is how he has, almost single handedly, selected Nigeria’s president since he left office in 2007. He not only selected them, he also deposed each of them as and when he felt done with each. Umaru Yar’Adua was his personal choice. When he was done with him, he came to Media Trust Dialogue in January 2010 and said the man ought to have resigned once he was sick. He was certainly the most outwardly figure behind the emergence of Goodluck Jonathan in 2011 but by 2013, he was done with him. He had already commenced discussion with General Buhari by the middle of December, 2013 shortly after scattering the Jonathan Presidency with a disclaimer of an open letter. Now, he has begun to criticise Buhari openly. As Generals, one may not make too much of that yet but he has started talking of the imperative of the ‘third force’ as a critique of both the PDP and the APC.

Obasanjo unmistakably among past Nigerian leaders in a group photograph in 2014

When we leave the presidential level, we count Obasanjo’s godsons in Nigerian politics and we wonder if any other player at his level has got that much, from the north to the south, from the east to the west. David Mark made Senate Presidency as an Obasanjo product. Bukola Saraki is an Obasanjo product. His late father got him into governorship of Kwara State as his concession for decamping to the PDP from ANPP. It was Obasanjo that granted the concession and enforced it. Jonah Jang of Plateau State, Magatakarda Wamako of Sokoto State, Ibrahim Shema of Katsina State, Sule Lamido of Jigawa State, Gbenga Daniel in Ogun State, Segun Agagu in Ondo State, Olagunshoye Oyinlola in Osun State, Liyel Imoke in Cross Rivers and several others were, at one time or the other, governors that Obasanjo installed. The strength of Rabiu Kwankwaso of Kano State is Obasanjo. Obasanjo forced Murtala Nyako to accept to be governor. And Obasanjo imposed his will on states of the South West by making the PDP the defacto party in the region from 2003 to 2011 or so.

Obasanjo is not the most senior of the Generals. That belongs to General Gowon. So, what explains why he seems to be the one who constructs and enforces consensus among the Generals and even the politicians on the question of succession each time it arises? He may be rich but wealth is unlikely to explain this since some other Generals are not church rats either. What does his accomplishment of a succession of installation and de-installation of presidents suggest to be the Obasanjo essence? With a capacity for ‘good’ and ‘evil’ in equal proportions, what might be Obasanjo’s value added and/or value subtracted from Nigeria and with what implications? In the concluding part of this report which follows in part two, we attempt to tackle these questions.