The mandarins of the digital tech space in the Western world ought to have been there to listen to the literacy concerns from a major site of consumers of their products. That site is Nigeria. Then they would have been able to respond to concerns such as how a child in the IDP can partake or coexist with the Michelle Amdo Ibrahims in the same Nigerian contingents to globalisation.

It is unlikely they would have said ‘Come on, stop trying to compel the rest of the world to slow down until you are done with your habits of the ‘Heart of Darkness’. Or something like ‘Stop your proclivity for tribal violence, corruption and carelessness’. To say that would be suicidal salesmanship in a populous continent by mandarins hooked unto the profit-maximising paradigm.

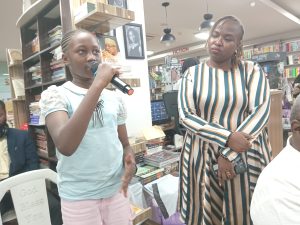

Michelle Ibrahim unfolding

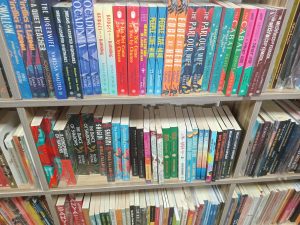

Imagining what they would have said was part of the stimulating tension which enveloped enthusiasts of literacy in the age of digital determinism in Abuja Monday evening on September 8th in the event jointly put together by Tunani BookClub and Rovingheights Bookshop. It was a straightforward event as it was a complex one. One ground of the complexity was stepping into a medium, well stocked bookshop in Abuja in Nigeria. That is contrary to the perception that everyone else in and around Abuja, Kano, Lagos and Port Harcourt is busy pursuing oil money or pursuing those who control oil money and not books and/or reading anymore.

Very much contrary to that perception, Rovingheights is a bookshop with a section on History/Politics, biographies, faith and what have you. And many of the titles are recent ones, including oven hot stuff. So, the next time a campaigner against philistinism over-generalises by saying no one is reading books in Nigeria, do not be intimidated not to call him or her a tale bearer. The more correct story is that Abuja or Nigeria, in fact, is a case of complicated coexistence between activists of mindless philistinism and book crawlers. No rule of inference will challenge a conclusion that if Rovingheights exists, then there must be other such bookshops in and around Abuja.

By the authority of Prof Jibrin Ibrahim who is more familiar with contemporary book activism, there is a whole lot of it going on in various forms across Nigeria, including places like Maiduguri, Gombe, Nasarawa and other troubled or sleepy state capitals all over the place. So, rethink oh ye who are thinking that the survival crisis has shut down the reflective industry in especially the most agrarian entities in Nigeria.

But literacy is part of the permacrisis – a concept which emerged from coupling two words – permanent and crisis. Permacrisis therefore needs no explanation. This event started with Mercy Kwabe and Maryam Ibrahim, anchorperson and welcome speech maker respectively, making reference to Nigeria’s figure of 18. 3 million out of school children, a UNICEF figure. That figure means there is already a literacy dimension to the national security crisis in Nigeria. It is because it means the Nigerian State which is the umbrella for all is not in a position to know what millions out of that figure will be doing at any one time.

The figure is then further compounded by the digital transformation that has occurred. Every such transformation came with a problem for information and communication. Orality had its own problem just as reading/writing does. It was the contours of the problems that came with digital transformation that was on the table this evening. Tunani BookClub and Rovingheights chose it as part of this year’s World Literacy Day commemoration.

The figure is then further compounded by the digital transformation that has occurred. Every such transformation came with a problem for information and communication. Orality had its own problem just as reading/writing does. It was the contours of the problems that came with digital transformation that was on the table this evening. Tunani BookClub and Rovingheights chose it as part of this year’s World Literacy Day commemoration.

It turned out though that a critical mass of suave digital warriors has developed in the country, with reassuring mass already exists in the Nigerian digital tech space. Again, it is an inference from the attendance at this event, not minding that quite a number of them trained outside. What is unique here is not just that those who spoke demonstrated comfortable mastery but a very critical sense of it. Critical in the sense that these are not people downloading stuff into their head on digital technology without interrogating them as and when due. All five members of the panel were relating to the theme critically. They knew which country they came from. The concern with how the child born in an IDP comes to grips with literacy in the digital era captures this grip with specificity. And it was a specificity common to all the five panelists who led the discussion before it was capped by Alhassan Ibrahim who, as moderator, told the story that sums up the standpoint tension in digital access ‘wahala’. It was the story of the fellow who injected ‘the which Abuja’ question when asked ‘how Abuja’. Instead of a mindless ‘Abuja is fine’, he asked: which Abuja? He was simply saying that Abuja is a universe in which each of us inhabit our own world even as we all live in the space by that name.

The story found its enunciation in the Michelle Ibrahim spectacle at the event. Michelle was, indeed, a spectacle, a one person grand performance actually. Just 10, she spoke in such a practiced manner that belies her age. She showed that she has simply been trained to master the attribute. So, she could tell how she overcame the literacy hurdles. It is the school she attended. And as she told Intervention subsequently, any other child from the school can replicate her performance. So, who says Nigeria is done for? Unlike some of the panelists who studied outside the country and whose mastery could be said to be understandable, she has, so far, got all her training in Nigeria.

The Michelle Ibrahims in Nigeria raise three observations cum questions. One, there are the children who have been able to domesticate the digital modernity because they have been groomed by the family and the quality of schools they attended. But how do the Michelles of this world escape entering the universities only to get drained by a system that is itself challenged? Third, how might Nigeria devise a system of identifying the Michelle Ibrahims in our midst and groom them into the set of youngsters who, in time, can take the country to where it belongs but without Nigeria being guilty of elitism? Food for thought!

A panelist successfully pushed the case for children’s books that reflect Nigerian geo-cultural environment into a consensus. The warning sunk in that if that pathway is not followed, our children will be learning A for apple stuff even as it will take majority of them long time to know what an apple looks like or whether apple is eaten raw or boiled. The problem is already here, said a panelist as there are children in Nigeria, including her own, who express desire to snow. As snow doesn’t fall in Nigeria, every such wish is an example of cultural distortion.

A line-up of the panelists

Prof Jibrin Ibrahim brought up the larger context. In the aftermath of the Nigerian civil war, the elite came to the consensus that never again should that sort of violence happen. To reify this, they found a policy pathway which said every child born after the war must be socialised to internalise the very values that would stand guard against explosive centrifugal consciousness. That was how the Universal Primary Education (UPE) scheme came up in 1976 but only to stop shortly after. Why? There were no teachers. The Nigerian State responded with a programme of accelerated training of teachers. That was how teacher training schools sprang up in large numbers. It is the origin of the acronym ETC – Extra Teachers who could Teach. This too didn’t fly

It didn’t fly because the real problem was that each of the three levels of government in Nigeria didn’t service the budget to pay teachers. The worst affected are rural schools where learning is conducted under mango shades and sundry structures across Nigeria even to this moment. And the giant of Africa didn’t feel embarrassed about that. Did I hear Prof Jibo concluding that if we have AK-47 or Kalashnikov – wielding bandits and terrorists all over the place today, one sure condition of possibility for that is the shoddy way we do our things in Nigeria.

Today, the baggage of the past has been compounded by what some members of the panel call the access crisis when it comes to digital modernity. The expert here is Omoniyi Lawson, one of the panelists. He identifies the two forms the access crisis manifests. One is the cost of data while the second is the cost of devices, particularly owning a smart phone. Anyone for whom any of these is out of reach is already disadvantaged even as the digital landscape in Nigeria is massive at 258 million phone subscribers. But the information from the field points at spaces in Nigeria where, until very recently, there were principals in rural schools who didn’t know how to send emails.

The good story though is that things are changing or have changed a lot. The ‘Universal Service Provision Fund’ is one key trigger for the change. As the experts explained it this evening, it is a fund meant to expand connectivity in secondary schools. Every country has the fund. In Nigeria, it has added value, what with about 300 schools in Abuja alone having benefitted. But is it enough? The answer that echoed is No. Nigeria needs to do more, particularly about data access.

There was the moment of ‘mischief’. It was in Alhassan Ibrahim asking the question: when last did you read a book? Uuuuuhhhmmm!

But it was a refreshing evening. Tunani BookClub had made possible an opportunity to see the danger in not connecting literacy in the digital civilisation to national security at an event where there was no praise singing and mediocre speech making. It was a productive 3-hour ‘detention’.