By Adagbo Onoja

No matter how tight deadlines some of us are confronting, we must make time to report the passage of Wahab Page. He died about a week ago if we follow Dr. Linus Akor’s Facebook posting to that effect. Dr. Linus Akor used to teach Sociology(Not Mass Communication) at the Department of Sociology, Kogi State University, Anyigba, but from where he left in 2017 to the Federal University Gusau, Zamfara State, where he is currently an Associate Professor of Criminology.

Dr. Wahab Page’s death brings back memories of a specific period in journalism and journalists in Kaduna metropolis. That is the category of journalists who considered it part of the everyday to frequent the Press Centre. They were about four or so of them in the mid to late 1980s if one is talking of the most regular faces at the well located Press Centre in Kaduna although one man’s regular faces could be another’s irregular faces. Both the old and the new Press Centre in Kaduna are very well located.

Page was a regular face at the center. He had a circuit. Within that circuit, he might have been a loud, assertive self but the mystique about him is he was the opposite of any of those outside that circle. Beyond enjoying that circle, it was difficult to see what he came to the center certainly on a daily basis. Of course, there is/was nothing a journalist wanted that s/he would not find in the center – meat, some form of food and all manner of drinks (mainly beer).

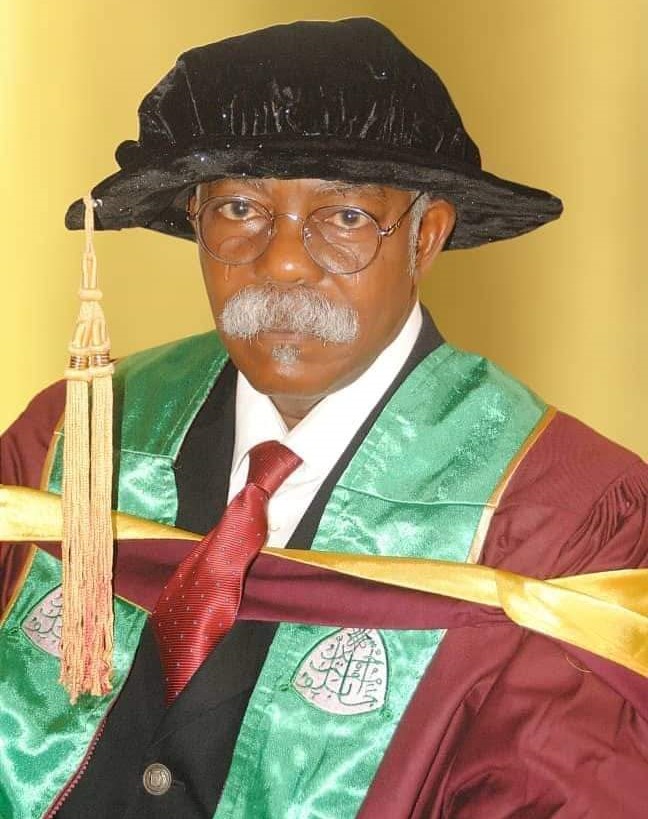

What Dr Akor revealed in terms of newness is Wahab Page leaving that level of interaction to pursue degrees at the Ahmadu Bello University. What is now known is that he went up to a PhD in Law. In other words, he is one of the not so many who effected a mid-life change of career line, making him a more solid player from the combination of the old and new professions. This owes to the fact that he is regarded as “one of the most efficient pioneer sub-editors of Sunday Triumph who made the first broadsheet newspaper in Nigeria what it was when it first appeared in 1982”, leaving the New Nigerian for The Sunday Triumph which he joined ‘the Haroun Adamu boys’ to leave when the Rimi era could be considered to have ended with the Sabo Bakin Zuwo governorship in October, 1983.

What Dr Akor revealed in terms of newness is Wahab Page leaving that level of interaction to pursue degrees at the Ahmadu Bello University. What is now known is that he went up to a PhD in Law. In other words, he is one of the not so many who effected a mid-life change of career line, making him a more solid player from the combination of the old and new professions. This owes to the fact that he is regarded as “one of the most efficient pioneer sub-editors of Sunday Triumph who made the first broadsheet newspaper in Nigeria what it was when it first appeared in 1982”, leaving the New Nigerian for The Sunday Triumph which he joined ‘the Haroun Adamu boys’ to leave when the Rimi era could be considered to have ended with the Sabo Bakin Zuwo governorship in October, 1983.

In accomplishing a mid-life career shift from journalism to Law, Dr. Wahab Page becomes a debate about whether any other profession can be superior to journalism. There are those who would say there can be none in the age of the discovery of the social as a product of articulatory practice rather than any non-discursive ground. Of course, there are those who would answer yes, generally and specifically. A major specific reason is the notion that very few journalists are able to make money. If they ever did, it is by entangling themselves with someone else because the media as a realm of investment confronts multiple baggage in countries such as Nigeria. Some of these arguments are neither here nor there anymore because the world has been changing.

Farther away from Wahab Page as a person, there is a memory block his death restates. There was the late A B Ahmed who became more frequent at the Press Centre after one of the ‘bolekeja’ scuffles in the now defunct New Nigerian Newspapers Ltd. A B as he was popularly called was ever capable of statements that would pass as explosive by ordinary standard of judgment. An Economics graduate of ABU, Zaria when the university was the all-round wave-making campus, AB was the archetype graduate journalist since the now dead Daily Times of Nigeria launched that phase in the progression of the profession in Nigeria.

Next must be Yunusa Aliyu of the NTA, Kaduna. He was a jolly good fellow who came to the centre to meet and mix and, in that process, pick one bit or the other about his work at the NTA.

No one could have missed Durosinmi Irojah then, whether during the early 1980s when he was what The Guardian called him – the Northern star – or when he was a consultant to Media Trust during the paper’s days in Kaduna where it started. Oga Duro is what everyone called him. He was there to play Draught. He was a smoker but one is no longer sure if he drank. Oga Duro was a very cerebral fellow. He got a First Class in Drama from the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria before the coming of the semester system. It meant he was the super intelligent type.

He used to work for the News Agency of Nigeria in one of their outposts – most likely UK or US. Then an National Party of Nigeria (NPN) mandarin went on a visit there. The big gun invited the correspondent and expected a story to be fabricated. Oga Duro was not used to that style of doing things. The mandarin was shocked that a correspondent of a FG owned medium didn’t know how to create a story about a visiting party leader. In fury, he demanded the recall of Oga Duro. That was how Oga Duro came back to Nigeria but smiling his way into the newly born The Guardian. In the 1980s, The Guardian was the place to be for any journalists who sought to operate at an elevated level. It operated beyond the craftsmen’s club in the profession. The Guardian took news as a discourse, long before the outbreak of the discursive turn in Europe and the rest of the world, situating every event in its larger context, much earlier than Christine Amanpour’s dismissal of objective reporting in her coverage of explosion of Kosovo.

The other most memorable alternative to the Press Centre which was directly opposite it then, unlike the present Press Centre

Oga Duro was a gentle soul. He came hard on you but through the frame game. No verbal missiles nor caustic assaults. If, as a news writer or proof reader or whatever, one muddled up a script, he gave you a name. That is how Hajiya Zainab Okinno, Adagbo Onoja, Dennis Mordi, Isyaku Dikko and many more got the nick name ‘mudi’. ‘Mudi’ was his cryptic for someone who muddled up. People working under him were muddling things up because, when Media Trust came newly on board, production was an all-night, manual affair every week. Somehow, there must be a slip of the pen or the eyes at some point between 12 midnight and 4 am. Someone among the production crew must doze off in one of those tough production hours. Or someone would fail to proof read a script thoroughly. No such slip will escape Oga Duro’s check. In each case, he will call out the name of the ‘culprit’, giving him or her a label.

We must add the late Abdulrahman Black to this list. He was one of those expelled from the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria in 1981. He was the president of the student union then. Somehow, he didn’t seek admission to another Nigerian universities or abroad which was what many others affected in that expulsion spree did. He was circulating between journalism and the segment of the trade union movement that understood the ideological character of the expulsion.

Black sought to be Kaduna State Chairman of the NUJ at a point in the mid-1980s. one became his campaign manager. But the overwhelming numerical advantage state ministries of information enjoy in electoral politics of the state chapters of the Nigeria Union of Journalists (NUJ) made his victory impossible. There were other factors too but the campaign was interesting. Even the winners could not but confess to the Black challenge.

Black was not one of the journalists who came to sit down at the Press Center for any length of time. he breezed in and breezed out. He merely kept in touch with that space. Ideologically, it was clear that he operated at a higher realm of abstraction than many of us who had not tasted undergraduate studies. But he had a socialist bent. We disagreed on one point. He would say we should go and watch a cultural performance or sit in an open place where some lumpens were dancing or doing their own thing. Neither one’s hamlet upbringing nor the Catholic orientation from the secondary school had prepared one for such a space of circulation. But he always won: don’t you see human beings being happy, he would ask in a manner that puts it to you that socialism is also about that. Now, from the point of view of popular culture, he is completely agreeable.

Adieu, all the faces of journalism that one can pick as it was in those days in Kaduna. With banditry, terrorism, kidnapping and exclusionary politics rocking Kaduna, it would be interesting to know its defining features in the spaces of journalism.