The United Kingdom, like much of the Western world BUT unlike much of Africa, is a key battleground involving troops of the decolonial epistemology, a battle well brought into view by the author of this piece reproduced from Unherd.

“They Kant Be Serious!” ran the headline in the Daily Mail a few years ago, above claims that students at SOAS wanted to do away with the likes of Plato and Descartes as part of efforts to “decolonise” the curriculum. Now, a mixed team of undergraduates and academic philosophers at SOAS have produced “Decolonising Philosophy: A Toolkit”, giving rise once again to anger and incredulity in Right-leaning newspapers.

The spectre of the “woke academic” has haunted public discourse, on and off, for years. It grew out of an older, broader disdain for humanities staff in particular: purveyors, it was said, of a pointless and politically-motivated education, in exchange for which students racked up enormous debts. Prominent, now, on the charge sheet is the claim that we confuse, in our writing and teaching, the encouragement of critical thinking with the preaching of a particular line on vexed questions of identity politics and social justice. Worse still, we do it using the linguistic equivalent of what my old headmaster used to call a “notice-me haircut”: a stream of fussy, high-sounding abstractions, infused with a sense of moral superiority.

The new SOAS guidance offers up plenty of red meat for those committed to this view. The prose is a little portentous in places, and the usual linguistic suspects are all present and correct: heteronormative, whiteness, coloniality. There is also the old trick, pioneered by Sigmund Freud, of pre-emptively defending your ideas by making opposition to them a symptom of psychological deficiency — in this case we find “institutional gatekeepers” potentially locked in a “subconscious struggle” to avoid sharing their power.

And yet the clever thing about Freud’s trick was that sometimes he was right: one really might oppose an idea on apparently intellectual grounds without recognising the emotional charge involved. Beneath my frustration with some of the toolkit’s prose (“coloniality’s operational life” — was there really no other way of putting that?) lies a certain amount of wounded pride at what can feel like undergraduates schooling me on how to teach.

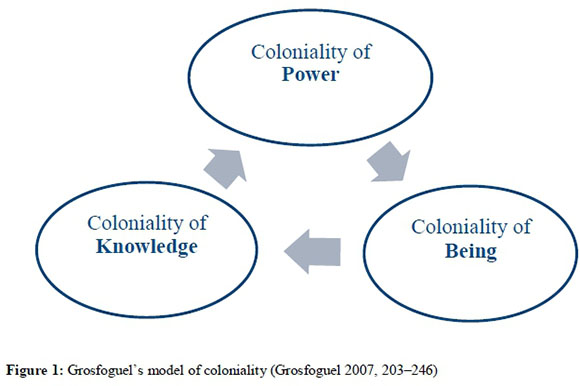

If I had a criticism of efforts to decolonise university curricula, it would be that they rarely give enough space to defining “colonial”. The historical insight at the heart of efforts to decolonise this or that aspect of contemporary Western life is that modern European colonialism was about much more than boots on the ground. Cultural seeds were sown via colonial and missionary education systems, the ways that colonial bureaucracies categorised people, the respect in which Western intellectual output came to be held and the felt need among some colonised people to acquire certain skills or adopt certain ideologies in order to get ahead — or even survive — under colonialism.

Leaving aside for a moment the question of which of the Western ideas involved were good or bad, the point is that they put down deep and stubborn roots, becoming a kind of cultural knotweed. Colonisers were affected too, as people in countries such as Britain and France were fed warped understandings of the non-Western world and were encouraged to take it for granted that their own ideas and standards — moral, political, civic — enjoyed universal applicability.

A good historical and moral case can be made for decolonising our knowledge in this sense: recognising and tackling entrenched habits of thought, sometimes in painful and humiliating ways where difficult topics including racism and religion are in play. If that case is not made, or is made badly, then public sympathy beyond our universities may be in short supply — especially if the word “colonial” is misconstrued in some quarters in terms of anti-white racism, anti-capitalism or Western self-hatred.

“A good historical and moral case can be made for decolonising our knowledge.”

What does all this mean for philosophy? What it clearly doesn’t mean is getting rid of Socrates, Aristotle and Plato on account of them being pale, male and stale. It is more about treating them as part of a particular tradition that has gained outsized influence because of the economic and military power of Europe and the wider West in recent centuries. What we need is a more comparative approach to philosophy, putting different traditions and individuals from around the world in conversation with one another. As one of the creators of the toolkit, Paul Giladi, tells me: “Good ideas are not restricted to any particular geolocation.”

This is harder than it might sound. It is surprisingly difficult to avoid using familiar categories when approaching new ideas or cultures. Students of religion find themselves tempted to use the Abrahamic faiths as a yardstick in exploring other traditions: looking for a personal God, a holy book, a set of beliefs. Mental health professionals trained in the diagnosis and treatment of conditions such as anxiety and depression likewise find that applying these terms too hastily in unfamiliar contexts means they miss something about the nature and meaning of the distress they encounter.

For Western students of non-Western philosophies, similar challenges lie in store. Across much of the Western tradition, being is the supreme principle of reality and self-consciousness the starting point of all our knowledge. In parts of Japanese philosophy, by contrast, nothingness is the supreme principle and self-consciousness a can of worms. Nishida Kitarō features in efforts at SOAS to decolonise philosophy, and he’s a good choice. Besides being a founding figure in modern Japanese philosophy, he serves as a warning against tokenism in decolonising our curricula. His Kyoto School of philosophy in fact owed much to German philosophy, and vice versa, encouraging us to think cross-culturally about how ideas are generated. The Kyoto School has also been subject to a great deal of opprobrium in Japan throughout the years, for what critics claim are its links to Japan’s own colonial project in the first half of the 20th century.

It’s good to see Confucius make the cut, too, at SOAS and elsewhere. Even that name tells a story. The man himself was “Kongzi”, christened “Confucius” by Jesuit missionaries who were among the first Europeans to explore Chinese thought back in the 1600s and 1700s. They did so, inevitably, through their own lens: making comparisons with ancient Greece and Rome, praising the idea of ethical action as a good in itself — as opposed to a means towards heavenly ends — and enlisting Confucius in their attempts to portray China to their compatriots back home as a sophisticated society that was ready for the gospel.

Takeshi Morisato, a philosopher at the University of Edinburgh, tells me that most universities cannot yet support the small classes required to really make the “open dialogue” approach required for decolonising the curriculum work well. Nor, he says, do most universities have enough staff who speak the languages and possess the life experiences out of which non-Western philosophies emerge. “Nothing,” he says, “beats having a few friends from diverse backgrounds who can be patient about each other’s intellectual blind spots.”

Decolonisation efforts in universities are big on “lived experience” and critics enjoy giving them a pounding for it: pure narcissism, or an abyss of “my truth, your truth” relativism. And yet surely the lives and experiences out of which philosophical ideas emerge are part of their richness. Arthur Schopenhauer’s rather grim view of human life somehow makes more sense once you know that he suspected the worst whenever the postman called and slept at night with loaded pistols by his bed.

If we instead treat philosophical ideas in the abstract, we lend them an aura of universalism and authority that they don’t necessarily merit. All we learned at school about the life of Immanuel Kant was that he ate cheese sandwiches because he was too busy thinking to cook. And perhaps even that wasn’t true. Paying attention, instead, to the roles of identity and lived experience, including those of students, in generating philosophical ideas and arguments needn’t mean giving up on evaluating those ideas and arguments.

Involving students in the creation of such curricula is surely a good thing, but here as elsewhere there’s a balance to be struck. At one point, the SOAS toolkit talks about “enabling (students) to identify what they need to learn”. In my experience, some students enjoy this challenge of co-creating a syllabus. Others wonder what they are paying upwards of £9,000 a year for if they’re required to do so. As Bill Murray puts it, eating shabu-shabu with Scarlett Johansson in Lost in Translation: “What kind of restaurant makes you cook your own food?”

One of the challenges for the decolonisation agenda is to avoid conflating a healthy inquiry into the conditions of our knowledge — historical, political, racial — with the pushing of a particular political agenda. Another, says Morisato, is to avoid simply making a pretence of decolonising the curriculum — “complying with liberal language on campus” — as opposed to embracing the radical nature of the project.

I think he has a point. Much of the culture-war hand-wringing over decolonisation stems from a sense that the other side is speaking or acting in bad faith. But if us woke academics can invest some energy in generating a quality of trust with our students that overflows beyond the classroom, then our ivory towers may be good for something after all.

Christopher Harding is a cultural historian of India and Japan, based at the University of Edinburgh. His latest book is The Light of Asia (Allen Lane). He also has a ubstack: IlluminAsia.