A reader who can be called a wolf warrior is so provoked by the first part of this review of Professor Attahiru Jega and Campion’s essay on the state of election management bodies (EMBs) in Africa. The furious reader (even as polysemous as words can be) sent some photocopied stuff to Intervention about what he calls “a messy and procured judgment” from a Nigerian court last week, using that as illustration for his rhetorical question on whether democracy is alive at all in Nigeria.

The man is so angry and so clear to the point of saying that it will be the ultimate death of democracy should the Nigerian judicial authorities allow the judgment under reference to stand. But so angry that he did not quite make the distinction between the petition on that guber election and the particular judgment he is raking about. Given that the first part of the review of Jega and colleague’s essay that he was reacting to was published on November 5th, 2023, it is safe to assume that his anger is against Justice Ekwo’s ruling last Monday baring the National Youth Service Corps Scheme from denying issuing the embattled governor of Enugu State a discharge certificate. Clearly, the protester thinks the case in question is so straightforward that no judge should have entered such a ruling.

Intervention is not that knowledgeable about the Enugu governorship petition as to make any authoritative comments. The assumption is that the system in Nigeria must still be able to take corrective note of judicial pronouncements that elicit extreme bitterness like this. Unattended screams are dangerous because, in the social world, it is perception that makes people to act one way or the other.

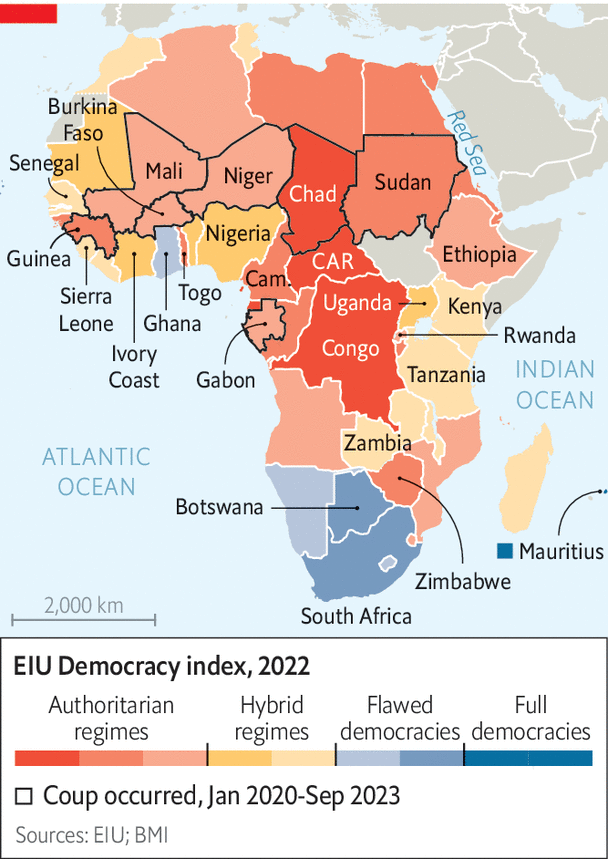

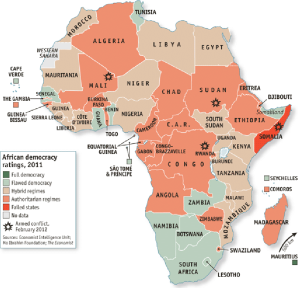

Others are talking about democratic backsliding in (West) Africa too

The point, however, is that Jega and his colleague’s essay fit perfectly into the struggle for democracy because every essay is an argument for something, the outcome of which can never be predicted. So, it is not necessary for every knowledge production exercise – essay, opinion piece, thesis, book, television appearance, etc to shout “crucify them, crucify them”. Methodical presentation of details is also part of the case for deepening of democracy. At a time when emotions and memories are at boiling point, it is not everyone who should carry fire on his or her tongue. In fairness to the protester, he did not blame Jega’s essay but made an automatic connection between the word ‘backsliding’ in the title of the essay to what he argues to be the condition of democracy in Nigeria. But Jega and colleague submitted their essay for consideration and publication since April. Its publication coinciding with court rulings in Nigeria are things no one has planned.

But the one-man protest which singled out Enugu governorship election petition under reference is also part of the dialectics of democracy. It is a dialectical thing that it is at the time democracy is so much loved by almost all that it is also under so much stress here and there. The frightening fear of the unknown, the enemy images of the ethnic, religious and regional Other and the suspicion and mistrust in there as well as the widening elite/mass gap are the very danger signals democracy is expected to cure through the principle of freely elected representatives.

There is thus a sense in which Jega and colleague are apt by drawing attention to a backsliding trend in the democratic field of play, globally, in Africa and, if Justice Ekwo’s protesting friend is to be believed, then in Nigeria. The essay by the two scholars told us that election management bodies (EMBs) which are at the centre of electoral integrity have advanced out of total control by one-party leaders, military henchmen and party mandarins but only to have come under manipulation, again, across the world. However, the details they relied upon did not show to them that the EMBs have totally crumbled, including in Nigeria, at least up to the time they wrote their essay.

The review stopped before the two case studies they selected and with which they hoped to demonstrate some of their claims. The case studies are Ghana and Zambia. There are reasons why they have been selected. One such reason is that they have been picked from two parts of the continent which have seen what the authors call marked overall declines in performance and autonomy. That is West Africa and South Africa although each of the two EMBs are credited with a track record of delivering peaceful elections and transitions of power between different parties since the mid-1990s. While the Electoral Commission of Ghana (ECG) got the applause in the 2000s for cultivating “high degree of trust and confidence … among citizens”, its Zambian counterpart – the Electoral Commission of Zambia (ECZ) is credited with delivering successive elections “broadly accepted as credible by stakeholders and observers” in the 1990s and 2000s before it began to grapple with challenges of weak independence vis-à-vis the executive. In other words, both have been experiencing unsteady, zig-zag fortune.

Electoral Commission of Ghana

The assessment of the Ghana EMB opens with a striking sentence that “Until 2016, all elections in Ghana had been presided over by the one ECG Chairperson, Kwadwo Afari-Gyan”, delivering a reputation for autonomy and competence in the face of highly contested elections that spanned two presidential run-offs and two changes of government. But the 2012 contest saw him in tension with the opposition. Although the procedural errors were not of that magnitude from what came out in televising the proceedings, his own language on television and the fact that his retirement was near watered the ground for what happened eventually: his departure.

Since then, it has been a cycle of what the authors call allegation of bias, legal tussles, increased scrutiny of successive EMB head in 2015 and in 2018 and above all, the amplification of these creases and areas of tension by the social media in particular. To this list may be added the regularity of international observers, actors such as the EU and the domestic civil society, signified in the case of Ghana by the Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO). It is perhaps not surprising the authors infer that “The decline in EMB autonomy in Ghana over the past 10 years is therefore not obviously a product of democratic backsliding”. Rather, they look at the fact that the leaders have not changed the electoral framework but, instead, tending to take the position of defending the ECG when in power.

Electoral Commission of Zambia (ECZ)

Electoral Commission of Zambia (ECZ)

The ECZ contrasts with the ECG, faced as it is from birth with challenges of autonomy, particularly from the president’s appointment and removal of commissioners, restricted financial autonomy and its dependence on local government officials for election delivery due to a lack of decentralised structures. This is compounded by a lack of proactive sanctions for parties and candidates who flouted adherence to an electoral code of conduct on campaign rules and electoral offences. Others are incomplete voter registers and ineffective regulation of competition between parties. It was not surprising that the tightly contested national elections in 2016 saw an escalation in abuse of incumbency and the suppression of freedoms of speech and assembly of the opposition. It reached prohibition of opposition gatherings through invocation of colonial era Public Order Act by the authorities.

Poor communication, opaque decision-making ahead of the election and a lack of transparency during the vote tabulation, verification and declaration, which were much slower than in previous elections, were reported as factors contributing to growing concerns about the partiality of the ECZ”

To make matters worse, the constitutional amendments of January 2016 to, among other things, update the presidential election system complicated the ECZ’s task of delivering the national elections and further worsened by corresponding changes were to the Electoral Processes Act and the ECZ Act just two months before the poll in question. The authors’ prose on the predictable outcome can be worth quoting at length: the late introduction and legal uncertainty around the new provisions meant that the ECZ was seeking clarification and adopting new regulations until two days before the election”. The PF candidate, President Edgar Lungu won the 2016 elections with 50.35% of the vote, narrowly avoiding a run-off. The result was challenged by the UPND, but the recently established Constitutional Court dismissed the petition on procedural grounds. The Carter Center concluded, ‘While considerable shortcomings occurred in prior elections … the 2016 elections signify a step backward for Zambian democracy”

The authors return an interesting verdict: The case of Zambia shows how the trajectory of EMB autonomy can be influenced by, but remain independent from, wider democratic backsliding. Many of the factors constraining the ECZ’s ability to deliver elections with integrity pre-dated the backsliding period but were exacerbated by the PF’s strategies, which put greater onus on the EMB to take on a more proactive role in regulating competition in line with the code of conduct. Its authority and credibility in the eyes of opposition parties and civil society, already fragile, were undermined by its inability (or perhaps unwillingness) to do so. At the same time, direct targeting or manipulation of the ECZ was limited”.

It is an interesting conclusion in that as pervasive as the manipulative grip on an institutionally less coherent EMB, we see a seemingly more organic civil society platforms. By name, a platform such as the Christian Churches Monitoring Group (CCMG) has a very specific constituency, not to talk of the more conventional civil society platforms.

At the end of the day, it is not a terrible thing for the authors to hold that the challenges facing EMBs are more than (democratic) backsliding and the ever present temptation for autocrats to try to strangulate democracy. As much as these are observable across the world, they have empirically grounded point in arguing that weak legal frameworks, new technologies, pandemics and natural disasters are also part of the problems.

The diversity they stress in terms of the factors which influence EMB autonomy and capacity tends to be confirmed by the case of Zambia and Ghana. While Zambia shows how backsliding can significantly undermine an EMB’s institutional integrity but without totally undermining an EMB’s level of functionality, that of Ghana shows that backsliding is not the only driver of decline but also escalating polarisation, particularly in the digital age, and the weakening of mechanisms that build political consensus around the delivery of elections vis-à-vis the perception and functioning of an EMB.

In the postmodern world, democracy is going to be a more and more complicated concept, more than anything people have seen so far. The philosophers who called it an empty signifier perhaps saw the handwriting on the wall and, unless voters take the notion of democracy as an empty signifier more seriously, they would continue to be left with the short end of the stick.

In a deconstructive language, an empty signifier implies something to be filled up. The implication is that democracy is a question of who filled up the signifier. All those putting so much faith on free and fair election, justice, freedom and such over-used concepts have not started the democratic journey. The travails of EMBs shows that training the ordinary people to know how to construct the meaning of democracy is the task that only people in Latin America have so far demonstrated competence.

There is no doubt that the essay just reviewed has enriched our empirical details about the state of democracy in Africa. We re-echo the earlier point that, mercifully, the essay which has just been published in the South African Journal of International Affairs (SAJIA) is an Open Access stuff, meaning that journalists, civil society actors, operatives of an election management body such as INEC in the case of Nigeria, members of the judiciary handling election petitions, politicians and sundry researchers can feast on it. That way, this review is merely drawing attention of readers to the existence of such an academic work waiting to be critically consumed.