When Intervention opened this series upon discovering that the late Bala Usman has a street named after him in Abuja, the reason given for the significance for that is that Abuja stands as a megacity in its own right. Abuja critiques the notion that modernity is not producing new Rome, London, Paris and other ancient global cities. At the time the Bala Usman Street signboard was sighted, it was not thought Claude Ake also has a street named after him in the glorious but distorted city. Or that Ake had a street named after him much earlier than Bala Usman, given that Gwarimpa where Ake Street is preceded the Kpaduma area where Bala Usman Street is. A Claude Ake and a Bala Usman Street is not about who got it first and at where but about establishment’s recognition of Nigerian scholars who would not have minded being included in the category of “dissident scholars”.

The dissidence that probably cleared the ground for dissidence of the post Cold War

Dissident scholars is the name given to the tradition of scholarship that interrogated and overthrew status quo ways of knowing in International Relations. In the jargon of authenticity, they are all post-positivists who brought down the iroko trees of status quo scholarship in especially American Political Science and the discipline of International Relations. Paradoxically, it was Stanley Hoffmann, an American scholar (or at worst a US based scholar) who started it all by writing the seminal essay that argued that International Relations is an American discipline – conservative and decidedly structured to justify American views and actions around the world.

Others took their cue from his 1977 essay and by 1984, Richard Ashley delivered the missile into the heart of positivist scholarship by decimating Kenneth Waltz, the all-time iroko and author of the masterful Theory of International Politics. It was only in the post-Cold War that it came to light that the attack on Waltz was misdirected aggression because he, indeed, ought to be the one to be called the father of the whole idea that reality is not a product of nature but of what we make of it (constructivism). The good news is that nobody attacks Waltz anymore because, in the matter of what constitutes theory, he has yet to be surpassed.

It must be part of the paradoxical character of reality that Waltz is not regarded as the father of post-positivism. It is rather the younger elements after him who are basking in the glow of that moment. It will be wrong to call them all postmodernists but it will be right to call them poststructuralists, although in truth, none of the leading names in that emergent tradition of scholarship applied any of such terms to themselves. It is other scholars who came after them that call them so. Similarly, neither Ake nor Bala Usman applied such terms to their scholarship.

So discerning

Both Ake and Usman were Marxists in their life time but if they were still alive, they would more properly be called postcolonial or decolonial scholars. It is still not clear if an Ake can be classified as a postcolonial/decolonial scholar but it would be hardly problematic for Bala Usman whose historiography is the nationalist lens – national bourgeoisie, national liberation, national autonomy, anti-imperialism, etc. Ake’s argument that it is analysis, not opinion, that matters, makes it extremely difficult to even contemplate associating him with post-positivism. However, the very interrogative or utterly dissident nature of his books as can be seen by the titles on parade here contradict that inferenc.

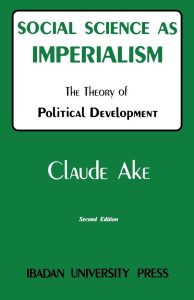

This platform would argue that Ake’s distinction is his level of domestication of Marxism and the boldness of his inferences arising therefrom. Social Science as Imperialism is a holistic rupturing intervention from Ake but A Political Economy of Africa is the stamp of his Marxism while Revolutionary Pressures in Africa is the stamp of his scholarly boldness. Some people may classify his intervention in the debate on whether Political Science can be called a science as the African genius in the world of scholarship because what he said in that essay is almost what has happened. It didn’t happen the way he argued but science itself has been so interrogated and almost dismantled to a point that makes nonsense of whether the question of the scientific status of any discipline at all can still be raised. In that sense, his analysis that the fact that a problem has not been solved doesn’t mean that it cannot be solved has come to pass. And yet, Ake is an African, the same Africans that are said to be incapable of theorising. Thanks to God, decoloniality is reversing much of that coloniality of modernism. Death robbed Nigeria of the sort of Nigerians the world should have been celebrating.

The question we are still grappling with

It is thus of significance that Ake, Bala Usman and many more have streets named after them in Abuja. It could be the sign of better things to come, especially as more naming is going on. A cargo facility in Anambra State has just been named after Achebe. That’s very welcome although we are expecting Prof Soludo, Anambra State governor, to rethink that by naming a cultural center or a university rather than a cargo facility after Achebe. It is possible that a cultural cum foundational reasoning informed that particular naming decision. That would be understandable but doesn’t make the connection between an Achebe and a cargo facility acceptable. The point is that Achebe is no longer an Igbo man. In fact, he is no longer an African. He is a world man. The academic who forced a particular Achebean formulation of the crisis of the ‘African condition’ in a Western university on me recently has no African blood in him. But, for him, my argument had to go unless I could produce a better alternative. Achebe has gone far in these matters and it is crucial that whatever ways Africa remembers Achebe references the intellect or serves as reminder of that prodigy about him. He certainly didn’t get everything right. None of us is expected to get everything right. What is expected of each and every one of us is to be able to signpost and/or add one plausible alternative way forward. He scores nearly 100 per cent in that.

Intervention would bet it but Soyinka and the other giants in Literature from Nigeria have a street named after them in Abuja. Add to that the whole set of the pioneers of the Ibadan School of History who may be understood today as pioneers of decoloniality. Almost every Nigerian university up to the late 1980s had its own batch of that generation. They all constitute Nigeria’s share and stock of the African genius, thinking about whom constitutes a crucial power resource for the remaking of a nation. Hence the idea of Ake and the phrase ‘back to the future’.

Ake and the culture of boldness: is democracy a necessity for development?

What we don’t know is whether sufficient scholarly works are going on about these scholars, reframing, adjusting and improving their arguments and conclusions. The signals from the universities as they currently exist doesn’t suggest so. Jeremiah Arowosegbe, the University of Ibadan political scientist is known to have published on Ake but can we be sure that his undergraduates and graduate students are reading him, interrogating both himself and Ake?

It is most unlikely if such is happening, given what Yemi Ogunbiyi just told the News Agency of Nigeria about the university system now. In spite of Dr. Ogunbiyi’s politeness of language, careful readers will get the message that he said the university system in Nigeria has been buried. President Buhari performed the formal burial rites with his incomprehensible IPPSS ‘innovation’. The expectation that President Tinubu will quietly and quickly interrogate that burial has not materialised. It is possible that is going on behind the scene but any such action should be the most publicised government programme because the rehabilitation of tertiary education is the basis for any possible renewal of hope!

This is nothing comprehensive about Ake or any of the giants of those days but if this piece triggers any reflective engagement on those men and women in any quarters, Intervention would have been fulfilled! Contrary views, alternative interpretations and new information are absolutely welcome as such will enrich our stock of knowledge on these departed academic pace setters. Every ideological, regional or analytical template is welcome.