BRICS is in the news this week. For a long time to come, it will be in the news, more so for Africa. As the most unintended biting critique of the ‘Clash of Civilisations’ paradigm, the idea of the BRICs before it became BRICS was/is where any African nation would wish to be. It carried a mystique and packed a punch in the cultural or civilisational diversity it embodied (Confucians, Hindu nationalism, Latin Americanism and the Orthodox Church); the demographic profiles encased in it and the paradoxical allure of three of its original members being nuclear armed nations. There could be no more alluring diplomatic space.

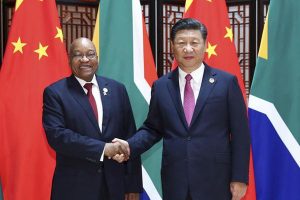

Zuma and Xi Jinping, the architects of the reconstruction of BRICs into BRICS

But which African nation could that be? Going by the criteria listed by Jim O’Neil, the then Goldman and Sach investment banker who coined the acronym, the cap fitted Nigeria more than any other, especially on O’Neil’s criteria of demographic profile and a space for bounteous returns on investment. He was looking at emergent but functional and performing economies. In one sentence, he put it this way: At end-2000, GDP in US$ on a PPP basis in Brazil, Russia, India and China (BRIC) was about 23.3% of world GDP. On a current GDP basis, BRIC share of world GDP is 8%”. And, in another sentence, he came up this way: If the G7 was to become a forum where true worldwide economic policy co-ordination was discussed, the US, Japan, Germany, France and the UK would be joined by China and India rather than Italy and Canada if PPP weights were the appropriate judge”

So, O’Neil wasn’t about mentioning Nigeria or any African countries in his original list from which the acronym emerged: Brazil, Russia, India and China. Apart from India and China, Russia and Brazil were not particularly looking that promising. It is part of O’Neil’s investment perceptiveness that he put those two. It was generally the profit motive that even enabled him to make the pronouncement in the year of 9/11. Today, BRICS is a geopolitical behemoth, beyond anything O’Neil thought about.

But what happened subsequently left O’Neil himself shocked. He was completely taken aback by the admission of South Africa into the group although that was not the first amendment to his original idea. BRICs had been made into BRICSAM the M standing for Mexico) in some quarters before it became BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) before finally becoming BRICS. The M in BRICSAM stood for Mexico but which dropped off in circumstances one cannot explain immediately.

O’Neill, the ideas man in this case, who was seeing investment openings in China, Brazil, Russia and India, specifically for their huge population and market, saw no reason to include a country such as South Africa for the same reason that he did not include South Korea because, even as developed as South Korea, it is sparse on population.

South Africa can rarely score any other diplomatic coup as this and there is no point denying it the credit

BRICs (when South Africa was yet to be admitted) is a perfect testimony to the wooliness of constructivism as a theory of international relations. Constructivism is the argument that what we see as society have nothing natural about them. They are things which sedimented into regimes or routine practices over time, products of language, ideas, norms and culture. In the case of BRICS, it was an idea which became an institution. But constructivism is a very weak theory because of its combination of conservatism and ultra radical spectrum in the same proportion. While O’Neill occupied the conservative spectrum of it, listing GDP, market share and investment potentials, the political leaders of BRICS occupied the radical end. Once the idea got off ground, the political leaders began to read it from their own lenses. The idea of such a block as a counter weight to West hegemony took centre stage. This came clear in one of the early communiques where they expressed the desire for ‘‘a more democratic and just multipolar world order based on the rule of international law, equality, mutual respect, cooperation, coordinated action, and collective decision-/making of all states.’ Still, South Africa was not on the card.

South Africa came on by chance. The idea of filling the African void in the new community might have been boiling in the South African foreign policy furnace but it only got the opportunity to be expressed for the first time in 2010 in Brasilia. The IBSA (India, Brazil and South Africa) Dialogue Forum had just ended a meeting. As the South African delegation was leaving, the Chinese president was flying into Brasilia for a different commitment. Then President Jacob Zuma seized this unplanned meeting with Xi Jinping at the Airport to drop the hint about South Africa’s desire to be admitted into the club.

BRICS now beyond anything of O’Neil’s imagination of it, having transformed into the hottest geopolitical player around

It is said that Xi Jinping is so smooth that he doesn’t operate in terms of a yes or no kind of answer. It is possible in that encounter that Zuma got an answer that got the entire South African foreign policy establishment into what Chris Alden of the London School of Economics calls BRICability. In other words, South Africa went to work full blast at the time Nigeria was debating whether a Goodluck Jonathan could succeed an Umaru Yar’Adua. At the end of the day, South Africa got it, leaving the rest of Africa and, in fact, the black world, shocked. Countries such as Nigeria, Senegal and Egypt which manifest a sense of entitlement had been left behind. And there it remains till today.

O’Neill was so non-plused about it that he vented his displeasure openly. And he did this in South Africa. The South African authorities left him in no doubt that he was overstepping his bounds. South Africa has consolidated membership, notwithstanding O’Neill’s criteria.

It is not clear if Nigeria foreign policy establishment (foreign affairs, the military, the think tanks and departments of political science, History and culture) ever sat down to reflect on what happened and the lessons to be learnt. Nigerian foreign policy, like her domestic politics, is circumscribed by question-begging categories of facts, figures or the truth rather than the articulation of her own instincts into universal acceptance of whichever audience it is dealing with at any one time. The risk is being left with the short end of the stick or by-passed in most cases. There are no foundational grounding in the social world. Everything is relational and criteria can be reframed. There’s the fact of a thing and there is the condition of possibility behind every fact. The two things are completely different.

However seen, BRICS membership is a head start for South Africa although her admission leaves the message that any other country can work on it and get in. How others can get in without making it an all-comer club is the question that must have dominated the current outing in South Africa. It would appear that BRICS has no alternative to going back to read again Jim O’Neil’s original essay. If it does, O’Neil’s idea of BRICS as the G-7 of the Southern hemisphere might be the way out. A likely outcome is one or two more countries from Africa, same from the Middle East and then there is a G-9 and that’s all.