By Ike Okonta

I have just finished reading David Levering Lewis’ two-volume biography of the African American intellectual and architect of the American Civil Rights Movement, Dr W.E.B. Du Bois. The two books won the Pulitzer Prize an unprecedented two times and cemented Professor Lewis’ reputation as one of the world’s leading biographers and historians. The prose deployed in the books is sinewy and lyrical. The argument is engaging and muscular. The overall effect is one of joy and gratitude – that an African American historian would pay tribute to one of the world’s greatest intellectuals in a manner worthy of great literature.

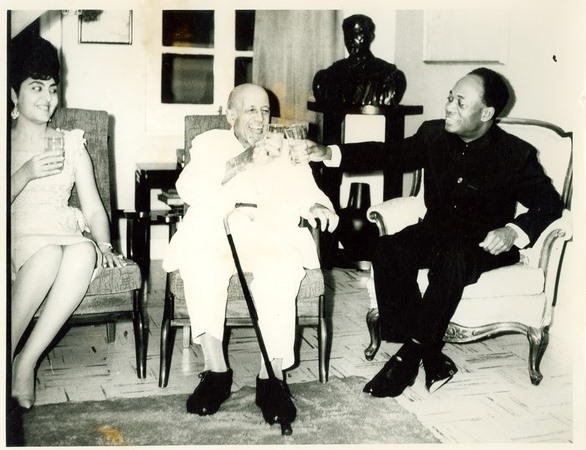

Guess who? Dr. Dubois and Dr. Nmandi Azikiwe, aka ‘Zik of Africa’

Dr Du Bois, for the uninitiated, was born in Massachusetts, United States, in 1868. He died in exile in Kwame Nkrumah’s Ghana in 1963, at the ripe age of 95. Du Bois packed into a long life activities including journalism, political activism, and fiction and non-fiction writing. He was the first black American to earn a doctorate in Sociology in Harvard University. He was to quickly prove that he fully deserved his PhD. One of his earliest books, The Souls Of Black Folk, is still read all over the world today and taught in leading universities. His other books include Gift Of Black Folk, Black Reconstruction and The World And Africa. It is in these books that Dr Du Bois gave to the world such concepts as ‘Double Consciousness,’ ‘The Talented Tenth’ and the twentieth century being the century of the colour line.

Dr Du Bois is also hailed as the father of Pan-Africanism. As early as the year 1900, he called a meeting of black intellectuals and political activists in London and charged the gathering with the task of reviving the economic and political fortune of all people of African descent in the motherland and the diaspora. It was in the speech he delivered at this historic meeting that Du Bois prophesied that the twentieth century would be a very turbulent century politically and that non-Europeans in Africa and Asia would rise up to challenge the hegemony and imperialism of Europeans. Du Bois was to follow up this 1900 meeting with several congresses of the Pan African movement, culminating in the epochal congress in Manchester, United Kingdom in 1945 where the likes of Kwame Nkrumah and Jomo Kenyatta came into their own.

Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe, one of Nigeria’s leading nationalists, was directly influenced by W.E.B. Du Bois when the former was studying in the United States in the late 1920s. One of Azikiwe’s earliest journalistic pieces, an essay on the killing of Igbo women by British colonialists during the Aba Women’s War in 1929, was published in The Crisis, the very influential monthly magazine of African American affairs which Du Bois edited at the time. As an undergraduate in the Nsukka campus of the University of Nigeria in the early 1980s, I was thrilled encountering the names of prominent African Americans on several university buildings. The fiction section in the university library was also stocked with the works of the leading African American writers of the 20th century – Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Ralph Ellison among others. I read these authors with relish and was introduced to the life and travails of our black brothers and sisters in America. This experience shaped and continue to shape my politics.

It is, however, significant to note that Dr Azikiwe, who founded the University of Nigeria in 1960, did not name a single one of the buildings in the University after Dr Du Bois. I have often speculated on the reason. Could it be because Dr Du Bois was a socialist and indeed joined the Communist Party of the United States in the evening of his life? As is well known, Azikiwe was an arch capitalist and, in his writings, did not hide the fact that one of the major motivations of his life was to accumulate as much wealth as possible. Du Bois travelled widely in his old age and met such personages as Chairman Mao of China and Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union. The American government, which was at the time in a cold war with China and the USSR did not like the fact that Du Bois was fraternizing with the ‘enemy’ and, in fact, confiscated his passport for a period. Nnamdi Azikiwe, the ultimate pragmatic politician, might have steered away from Du Bois during this time so as not to offend the United States and Great Britain.

Dr Du Bois is not widely known in Nigeria unlike in Ghana where he is celebrated as a Pan African icon. This is tragic because Nigeria and indeed all African countries owe Du Bois a debt of gratitude. Without Du Bois’ path-breaking work in the early decades of the 20th century as an implacable Pan Africanist, the rise of the likes of Dr Azikiwe, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya and Dr Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana would have been inconceivable. Until he breathed his last in Accra where he was working on an encyclopedia of the African world, Du Bois hungered for the day when the countries of Africa and its diaspora would be able to stand up on their own and take their place in the comity of nations. He had total and unswerving faith in Africa and her peoples, and was confident that the day was not far off when the continent would astonish the world with her advances in culture and science and technology.

The Covid-19 outbreak and Africa’s laggardly response to it has brought home the brutal fact that Africa will have to swim or sink on her own efforts. The present situation wherein Africa’s ruling class since the 1960s have been looting the continent and stashing away the money in European and American banks must be confronted and a new Africa founded on the dreams that Dr Du Bois so selflessly and bravely enunciated allowed to take root. The best way to pay back Dr W.E.B Dubois is to simply continue the work where he left off – the project of a renascent African world taking her proper place in the world.

- Dr Okonta was until recently a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in the Department of Politics, University of Oxford. He presently lives in Abuja.