By Adagbo Onoja

The ‘Ochonyilo’ vocabulary is a gender insensitive idiom in Idoma, a celebration of manliness with performative implications for gender equity that Intervention would, ordinarily, not use. It has to be used in this piece because I doubt if a replacement can be found, a replacement that does justice to the memory of someone who did not hypocritically proclaim himself to be an angel but who satisfied the requirements of being a leader in his own way!

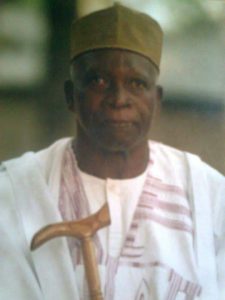

The news is that Okpani Benedict Oko Ochiga is gone to his maker. That might not strike those who never heard of him. Those who knew him will hardly dispute his death as the departure of the quintessential ‘Ochonyilo’ and would have difficulty contemplating the moment he will be dropped into mother earth. He had a pervasiveness that made thinking of him in the past a distant thought.

It is not that he was what is known as Omajakleku in the Idoma world view, (the effant terrible in English). By the authority of a Professor of Idoma identity who tutored me on this in Zaria, Omajakleku is the child who circumcised his father. That is the perfect mystery child. Okpani Ochiga wasn’t that complicated. He was more of a case study in extraordinarily fierce and individualistic assertiveness against perceived aberrations and his sense of self-satisfaction from the associated heroism. It is the absolute fearlessness and forcefulness in accomplishing his heroism that define the rarity he was in life.

Another view of him

The rarity makes his death a subject of reflection as a critique of invisibilisation which I crudely define here as the practice of making some people invisible at the expense of others. Our sense of the struggle for emancipation enjoins us to fight invisibilisation by making the invisible visible at whatever level, a process which Queen Mary University of London’s Prof Sophie Harman has beautifully shown the way with her award winning film, Pili – story of living with AIDS as told by a Tanzanian woman. It is in the same sense that attention is being drawn to Ochiga’s rarity beyond himself even as Intervention is supposed to be observing a moratorium on deaths and burial.

There would be nothing outrageous to say that, until early morning of November 12th, 2021, there were two of them in the entire Edemoga District of Okpokwu Local Government of Benue State in central Nigeria. One was Chief Michael Ogboji who died in 2014 and the other was Okpani Benedict Oko Ochiga. And they shared very similar pedigree in their progression from rough riders into referential personages at their point of death. While Ogboji died as the Clan Head (I am not sure of this title since many of the clans have been broken up and renamed), Ochiga died as a leading politician. None of the two had much formal education but there was nowhere or any audience anywhere in the world they could not address and win over on whatever subject matter. Their turn of phrases, turn taking and non-verbal facilities were unique to them. And they all did this without being grandiloquent. It is part of the rarity we are talking about.

Chief Ogboji was my in-law before the relationship transformed to one of intense admiration for each other arising, in my own case, from the awe he inspired in whoever listened to him, especially on Idoma cultural boundaries. Similarly, Okpani Ochiga was the model’s model for young people growing up in Ogene in the mid 1970s. His own style of riding his CD 125 motor cycle into the village partly accounted for that. He did it in a manner that made it more fascinating than owning a car. So, we looked forward to when we too could be like him. Of course, stories of his audaciousness in the military and in urban life in Kaduna were spreading and exciting us as pupils. In all these, he came out as the very opposite of his equally famous senior brother, Patrick Ameh Ochiga – the considerate trade unionist who had gone on course to Britain twice as a textile worker and whose house in KTL Senior Staff Quarters in Kaduna served as the arrival terminal for job seekers migrating into Kaduna from the village. And even of Okpani Francis Adah, another tough but big minded member of the Ogene Amejo community concentrated in Kaduna then.

The late 1970s was time for relocation to Makurdi for Okpani Ben. Why he chose Makurdi will remain in speculation now that he is no more. It is most likely because Benue State had been created and offered its own attractions, especially for him who was ending up in hotel business. In fact, he named his Boriga Hotel. It was an interesting gender statement from him to be conscious of including the name of his wife for which the R in Boriga stood while the first two letters were the initials for his own names. The hotel has since suffered the fate of the Makurdi environment as a permanently agrarian urban centre. Whether it is the lack of prospects in hotel business that drove him into politics is also difficult to explain. It is unlikely. His intolerance for aberrations is the more likely reason as his politics was predominantly that of challenging perceived infractions by local notables. It was such a paradoxical thing. His devil-may-care shots at such infractions and its perpetrators constitute the reason he was blocked from many benefits but it was the dimension of his rarity at this point. It was also the reason he was respected for the tireless inclination to ‘speak truth to power’ at the expense of privileges that could have been his at many turns. He wasn’t always an outsider though.

The late Patrick Ameh Ochiga, patriarch of the Ochiga family of Ogene Amejo

Irrespective of which view of him anyone had, no one could ignore him even as they wished he was less stormy. Always neatly and appropriately turned out, he had transformed from an over-confident youngster into a thinker, strategist and cultural philosopher. Apart from the witticism and the resulting fullness of presence from his impeccable turn out, he had audience management. He showed this, for example, on the day he went to see Sule Lamido as Minister for Foreign Affairs sometimes in early 2000. The idea of a homeland delegation to thank the minister had been dismissed as contrary to the PRP ideology and spirit of my appointment. It was something trans-ethnic and trans-religious. So, why bring it down to the level of an Idoma delegation? So, the idea died. He was part of a wider audience that decided this. But, on this occasion, he said it did not mean that somebody from my place should not go and greet Lamido.

Ordinarily, Chief D. A. Adulugba, the late District Head of Edemoga, would have been such a person. But Ochiga was already in Abuja and there was no protocol involved in going to see the minister unlike if Chief Adulugba was to do it. He did and I would say his performance was fantastic. He was not intimidated by Lamido’s physical frame, position or the office size. I came away with the impression that Lamido found his match in witticism as the conversation between the two went beyond myself because of my poor command of Hausa.

Of course, he was the regular star around me. I cannot remember any home going in the past two decades that was not done with him in tow. It wasn’t that we agreed on everything. It was that he had a pointblank view of things, most times convincing. The way it worked was that if he thought I needed a dressing down, he administered a huge dose of it. If he thought I lacked good understanding of a particular issue, he provided it. If he felt sad that someone was taking advantage of my nature, he said so. He once told me to calm down over something that someone had done that I could never have expected from a person of that exposure. He said “not more than a few of us know the kind of person you are”. He set me thinking, reminding me of when Engineer Raphael Ola once asked me if I had learnt how to tell lies since becoming an aide to a politician.

But he was also everybody’s regular star. I can say this authoritatively in the case of Comrade John Odah and Ambassador Nick Ellah and too many of us from the area that he felt relaxed with, for whatever reasons. I define that too as part of his rarity – seeking out persons who were his juniors, asking after how they were doing in their different spaces and doing this from a position of strategic advantage in his better mastery of the cultural paradigms and practices than these younger elements. Imagine that he went farther in formal education, would he not have gone places beyond the height he flew? It must be a bleeding experience to know how many of such people our unique underdevelopment has kept away from fuller participation in modernity. That is the utmost dimension of Ochiga’s rarity that must be made visible.

It is doubtful anyone who knew him will deny him being an embodiment of the never-say-die outlook. He did what he could, such as enabling the local lyricist, Ada Atama, to make his first artistic outing, a major contribution to cultural identity.

On the whole, Okpani Ochiga appeared to believe completely in the narrative that calling the hawk names doesn’t kill the hawk but rather makes the hawk more robust. It must be that which enabled him absorb blows from here and there without ever caving in or looking miserable. His story cannot be told standing on one point. Some others would have to tell theirs now and later!