The federal solution as a way out of the phenomenon of state collapse in Africa is echoing again as Prof Eghosa Osaghae, University of Ibadan and one of Nigeria’s leading scholars of federalism attempts an answer to the question of whether federalism is a dead issue or a potential model for state-building/rebuilding in Africa?

Prof Eghosa Osaghae

Prof Osaghae who is STIAS fellow and currently at the University of Cape Town in South Africa says “The trajectory of state failure offers the opportunity to rebuild states in Africa”, adding how he sees federalism as the most appropriate model in the package of solutions it offers.

“Scholars of African politics tend to want to move on to other buzzes without clearing the most fundamental issue of states that are not working. My project is built on the premise of fixing states through federal solutions whose significance and utility have been grossly underestimated because of limitations of extant theoretical perspectives and praxis.”

“The exogenous origins and trajectories of states in Africa as colonial formations have created endemic problems of ownership and legitimacy that have inevitably pushed them to failure,” he continued. “However, contrary to what the dominant narratives suggest, state failure is not simply an institutional capacity or weakness failure, or a consequence of patently African pathologies and a return to the dark; it rather indicates that inherited state forms in Africa which reproduce Western forms in a false universal, limitations and all, have failed to work, finally unravelled, and fallen apart.”

A broader vision of federalism

Osaghae believes it is precisely this “falling apart” that offers the possibility of re-examining federal solutions to state-building, However, such solutions must be broader than just a federal state.

“I argue that sociological and political perspectives of federalism which relate federal solutions to the nature of societies rather than legal-constitutional perspectives that narrow the essence of federalism to constitutional strictures, provide the best frameworks for doing so,” he said.

He pointed out that federalism is at its height in countries like Germany, the USA, Brazil, Canada, Australia and South Africa. But that the models are very different.

“The system is about diversity. It’s not one size fits all,” he said. “There are different traditions and perspectives of federalism. It’s a system that allows for a variety of forms. It’s not universally cast but about the society that the federal solution serves.”

Although the most established is the legislative constitutional form, Osaghae believes we cannot reduce federalism to federal government. “You can have federalism without federal government. It is a sociological system, a political system that relates to the nature of society itself. No two systems are exactly alike. Every country works out a suitable version of federalism to suit the statehood.”

The different forms make use of elements of federal principles including sharing of territories, executive power sharing, governments of national unity, quota systems, systems of proportional representation, electoral democracy and affirmative action – but these are reflected differently in different settings.

The different forms make use of elements of federal principles including sharing of territories, executive power sharing, governments of national unity, quota systems, systems of proportional representation, electoral democracy and affirmative action – but these are reflected differently in different settings.

He also pointed out that federalism was very much present in in the pre-colonial history of Africa. These societies were not mono-ethnic, many had the trappings of modern statehood and elementary federalism often through the forging of military or economic alliances. “For example, some, like Ethiopia, had rotational kingships with succession based on negotiation.”

He highlighted the two trajectories of statehood creation. Endogenous – where states evolve from within with room for civil society to shape state formation. This is often established as a resolution of conflict and there is usually convergence between the state and social development.

“Such states usually evolve on the basis of consensus and federalism takes pride of place. People have a say and can claim the state as their own.”

The second trajectory is exogenous where states are formed from external forces. For example, through colonial acts of creation. Decisions on territory, language, etc. are made by the colonial authority with little regard for the preferences and rights of the people. This inevitably leads to a crisis of ownership and legitimacy with the state seen as a product of foreign interests and priorities. Even where these states purport to be federal it isn’t true federalism but rather externally imposed.

“This model has not done well in Africa,” said Osaghae. “The state becomes an object of contestation as it does not live up to expectations. By the late twentieth century this led to state failure in many African states. Leading to second, often conflictual, independence movements looking to re-appropriate the state.”

“The unravelling of such states is almost inevitable. The state cast is not founded on African precepts and needs to be rebuilt.”

“Federalism has to be related to the society it serves – the political economy, the social make-up, the culture, traditions, norms and values.” He highlighted the examples of South Africa and Ethiopia.

South Africa’s peaceful transition was a result of compromise and negotiation. “The bargains made at CODESA led to independence,” he said, “culminating in the adoption of a federal Constitution along with a government of national unity and elements like affirmative action and reverse discrimination. It’s not typical federalism but federalism suited to the democratisation of society, self-determination and the articulation of diverse interests.”

South Africa’s peaceful transition was a result of compromise and negotiation. “The bargains made at CODESA led to independence,” he said, “culminating in the adoption of a federal Constitution along with a government of national unity and elements like affirmative action and reverse discrimination. It’s not typical federalism but federalism suited to the democratisation of society, self-determination and the articulation of diverse interests.”

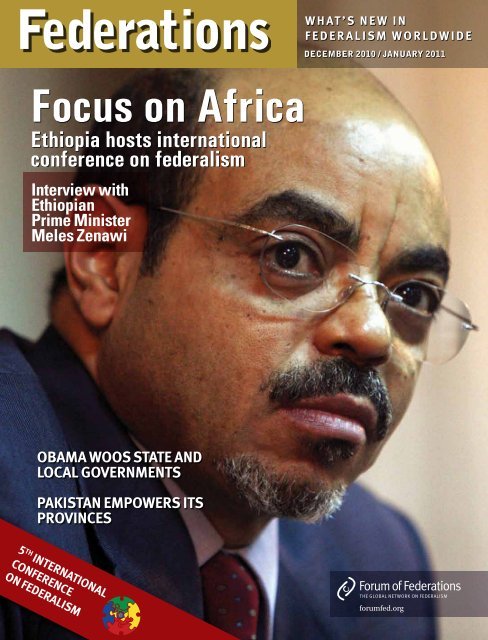

Ethiopia, similarly, came together in complicated negotiations in the early 1990s resulting in a version of what Osaghae described as “ethnic federalism”. “People feared one-party dominance,” he said, “but a secession clause was introduced giving the option to opt out – as was done by Eritrea. It’s a very forward-looking federalism – the states are not cast in stone.”

“The challenge is to see how we can rebuild African states through renegotiation and inclusive bargaining. The colonial states did not create organic societies, there was no foundation. States were handed over like balloons. The challenge now is to use an endogenous approach to rectify the mistakes of exogenous state-building. State failure offers the opportunity to bring this about.”

New realities, new instruments

In the discussion, he indicated that it will be interesting to see South Africa’s trajectory in the coming years. “The voices of the provinces have been overtaken to some extent by those of the political parties,” he said. “If difficulties arise there could be gridlock especially in provinces led by the opposition. Political parties remain important in South African politics. The President approached the parties before he approached the provinces in the COVID-19 response. The future could see further redefinitions of federalism. It will depend on the extent to which individual provinces see themselves as constitutional units – this is not yet the case due to the power of the ANC.”

But he also emphasised that new realities across the world may demand new instruments. “The current crisis could lead to a reconfiguration in the US. Federalism must adjust with new instruments that respond to new challenges.”

“This is the beauty of the federal framework,” he continued. “It’s elastic, allowing for dynamic changes, a product of changing democracy, not once and for all, but something that can be reproduced, re-engineered, reformed and recharged.”

“Federalism doesn’t have to be uniquely African but must be contextually African – including room for culture, customary rules, welfare,” he added. “The framework must be determined by the people and allow for different articulations. If people don’t have the room to make their demands, the state will be perennially unstable.”

“It must be organic, flexible enough to accommodate all and recognise that the things that bind us are more important than those that divide. People must find themselves in togetherness – which is more important than ever now.”