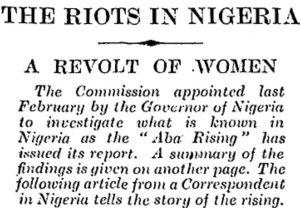

It is 2020 International Women’s Day and all manner of actors are identifying and posing their own puzzle about ‘The Women Question’. It is unlikely that any other actor will beat Gallup Global Analytics in terms of posing the most interesting question as far as this year is concerned. They are asking: How Far Is the World From Reaching Gender Equality? Gallup is sharing women in women’s own words on question of: ‘what do women want for themselves, their families and their world?

Flashback to Malala

It is the sort of approach script managers would call a masterstroke in empowerment in that it enables women to enhance their discursive power unlike when some do-gooders disempower them by articulating the problem on their behalf. In that context, Gallup is showing a very progressive example on the ‘The Women Question’.

But, long before Gallup, a literary intellectual had started on that track in a 2018 book by throwing the searchlight on what two particular women writers have to say on unequal power relations. In her own case, she selected what the women writers have to say on slavery and colonialism on the one hand and slavery and racism on the other hand, two of the most sensitive issues of our time. No occasion is more apt than today to review the book in question.

In so far as reality is constructed before it is naturalised in popular mentality, there can be no superior realm for the struggle to balance gender power gap than the literary realm. Whoever dominates the literary space dominates not only popular culture but knowledge and what knowledge can make commonsensical.

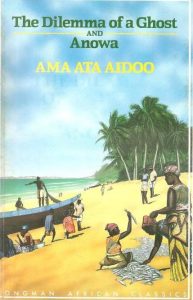

Driven by this consciousness, Dr. Monique Ekpong, an Associate Professor of African Literature and the author of Feminist Consciousness in Selected Works of Ama Ata Aidoo and Zora Neale Hurston set out to reduce male dominance of the literary space she encountered in the academic programmes she went through, from the University of Lagos, (UNILAG) where she took her First Degree to the University of Calabar where she did a Masters Degree before accomplishing a PhD in African Literature at the University of Portharcourt. To do that, she selected the two women writers, with particular reference to what their literary stuff tells us on the two themes.

The author delivers her finding in the eleven chapter book that offers a wealth of information on what women have to say, broadly and specifically, ending up with a book that automatically appeals to students of literary theory, postcolonial theory, Sociology of Literature, cultural studies, political economy of patriarchy, International Security, Peace and Conflict Studies and the geopolitics of civilisations.

The author delivers her finding in the eleven chapter book that offers a wealth of information on what women have to say, broadly and specifically, ending up with a book that automatically appeals to students of literary theory, postcolonial theory, Sociology of Literature, cultural studies, political economy of patriarchy, International Security, Peace and Conflict Studies and the geopolitics of civilisations.

While leaving each reader to discover for him or herself the creative rupturing of colonialism in Africa and racism in the United States of America from heightened gender lens, there are one or two general features that needs to be pointed out.

Students of methodology would find this a particularly interesting or even challenging text. This is because it is an interpretation of interpretation. In other words, the author is penetrating works that are themselves interpretations of the phenomena the women writers were confronting or making sense of. The philosophically involving nature of narrative analysis means that those who engage with this book will be getting two outcomes. That is, having to recall their grasp of narrative analysis to the help of meaning making as well as the radicalizing effect of the anti-colonial and anti-racist bent of the two women writers surveyed.

The second feature of significance to this reviewer is a matter of general information rather than specific literary issue. Reported in the book is the author’s encounter in Ghana that speaks to the fluidity of identity in West Africa. Prof Monique Ekpong had to travel to Ghana in the course of researching the book. There, she was to find that most of the cultural identities are basically the same as it is in Nigeria and they have even shared sense of this. That is, the Ejaghan, Bete, Mbube, Yala, Efik and most of the other ethnic clusters she met in Ghana are the same stocks in Nigeria. What is the point here? The point here is how those who push ethnic essentialism can only be people who have nothing worthwhile to do. It remains important to always pay attention to the sort of circumstances which triggers deployment of ethnicity in inter-group relations but that doesn’t mean ethnicity is not an invention, particularly given the way the forced migration called slavery scattered Africans. A fleeting aspect of the book but a significant accidental discovery!

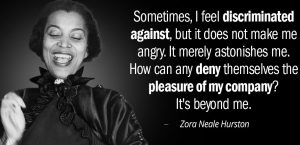

Zola Neale Hurston’s all time ridiculing of racism even as it persists because of the identity complex and profit that drives it

Now, these are just two examples of the sort of materials the reader will come across in this book. It is not surprising that Professor Akachi Ezeigbo, the literary amazon at the University of Lagos describes the book as brilliant, well thought out and typical of the author’s other outputs.

Prof Ezeigbo’s remarks cannot be reduced to the sort of approving comments supervisors make on what their mentees come up with. This text has put on the table the knowledge agenda of women creative writers of African identity who have not been studied as women and as black writers. Without preempting the reader, the book does bring out the dynamics of structural violence in each of slavery/colonialism and slavery/racism as communicated by the two women writers she studied. By categorically rejecting the sexist and stereotypical images of women, the author successfully shows how the two women writers deployed literature as a protest instrument against horrendous historical violence embodied by slavery, colonialism and racism, whether across Africa as in the literary works of Ama Ata Aidoo or in the Harlem, USA where Zola Hurston is culturally located.

Should Prof Monique tighten the literature background of the book into one coherent chapter and probably move the current Chapter Three into Chapter One in the Second edition, then we might have got a powerful intellectual intervention against the most successful case of naturalization of a lie in human history – the lie that women are inferior to men even as the sexual conquest of women define the average man’s life. What a paradox of patriarchy!