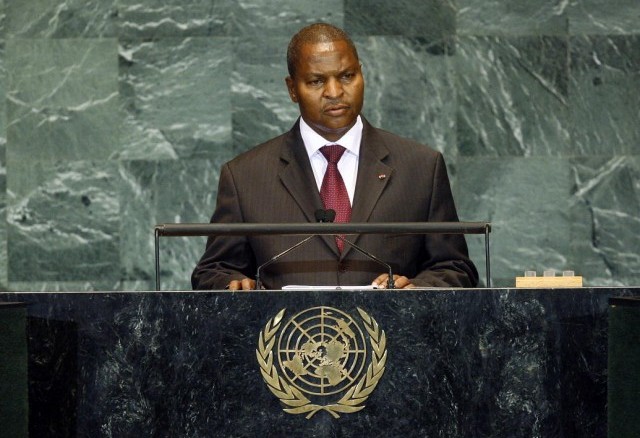

When the late Prof Ali Mazrui once suggested a process by which African superpowers could enforce peace on the continent, fellow African scholars mauled him no end. If he were still alive and were to restate the argument today, it is unlikely that his critics would be kinder but it is also unlikely they would be as vehement as they were in the late 1980s when Mazrui spoke. What does anyone do to the situation typified by what South Africa’s Mail & Guardian captured in this report below originally titled “Central African Republic, (CAR): The State That Doesn’t Exist”, (Dec 15th, 2017). The fictional nature of many African states in the sense conveyed in the italicised segment of the report below is something Africa must take a more serious note of. It just has to. The tragedy is how even the African superpowers such as Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt who should lead this process of taking note are themselves entangled in their own internal chaos that they can hardly do what Mazrui wanted, what with Nigeria and Egypt in protracted counter-insurgency operations, South Africa in a crisis of post-colonial political economy, leaving only Ethiopia and Senegal on Mazrui’s list then. Both the report and some of the graphics were by Simon Allison – Intervention:

Even in its best days, the CAR was never much of a state. But since the outbreak of civil war in 2013, the government has all but ceased to exist outside the capital Bangui. What happens to a town in the absence of any kind of authority? What does anarchy look like? The Mail & Guardian travelled to the country’s northwest to find out.

Imagine a country without a functionalgovernment, this is one at the moment

Imagine a country without a functioning government. Imagine a province where the rule of law has broken down completely. Imagine a town without any basic services or state institutions — no police, no schools, no courts, no civil service.

Imagine Batangafo. It is a small town, up towards the northern border of the Central African Republic (CAR), and even in its heyday it was little more than a few tree-lined roads of red dirt strung along a bend of the river Ouham. But it was calm, and orderly, with a local authority just about able to keep the peace and uphold some semblance of the rule of law.

Now, like much of the rest of the country, Batangafo is an experiment in anarchy.

The nightmare began in 2013, when rebels marched through Batangafo en route to the capital Bangui. Local government officials fled before them, as did most of the town’s middle-class professionals: its teachers, its doctors, its businessmen wealthy enough to escape. Few ever returned, leaving the 20 000-strong population to fend for themselves as conflict raged around them. Many now live in temporary camps for the internally displaced. Many more live in the bush, surviving on whatever they can scavenge.

Imam Abu Yusuf, head of a local mosque, had a front-row ticket to the town’s collapse. “Batangafo was a cosmopolitan place, it belonged to everyone … People danced, ate together,” he said, speaking on the enclosed verandah outside his tiny mosque, its minaret made from mud bricks piled several metres high. The mosque is much less busy than it used to be; nearly half of Batangafo’s Muslim minority have fled the town.

“Now, it’s sad. The town is different. It’s a ghost town … We need administration and justice, otherwise we will always live like this. We cannot keep society together if there is impunity. Now it’s jungle law. There is no law,” said Abu Yusuf.

A leader of one of the gangs that have replaced governance with their own version of it

Batangafo today is a dangerous, divided and largely deserted town. One side, along the river, is under the so-called protection of rebels formerly known as the Seleka — the armed group that overthrew the government of François Bozizé in 2013. They are usually now referred to as the ex-Seleka, although people here use the terms Seleka and ex-Seleka interchangeably. The ex-Seleka groups are better organised than their opponents, boasting a military-style hierarchy, although this year they have begun to fracture into ever smaller units, and are fighting among themselves.

The other side of Batangafo is controlled by an anti-balaka group. Anti-balaka is the term used to describe the loose coalition of self-defence militias formed to resist the Seleka. They don’t have any central leadership, or any real ideology, and the aims and tactics of each militia can vary wildly from town to town.

Both groups survive by taxing and terrorising the local population — the same population that both claim to be protecting.

Between these two armed groups, where the centre of Batangafo used to be, is a no-go zone except for United Nations peacekeepers and the few nongovernmental organisations that still operate here. Weeds grow through the foundations of Batangafo’s only permanent structures: its town hall, its police station, its municipal market, its schools.

For armed groups, the real prize is not Batangafo itself but the roads that lead into it. Control the roads and you control all the goods and people that must move along it.

‘Government has forgotten us’

In July, a tentative ceasefire between the armed groups in the area was shattered when fighting erupted along one of these roads. More than a dozen people were killed. Batangafo’s inhabitants, those who are left, were forced — not for the first time — to make an agonising choice: remain in their homes and risk being targeted by combatants, flee into the bush or seek sanctuary in one of those makeshift camps for internally displaced people.

Louisa Soubama (69) chose the third option. She ran into the grounds of the Batangafo hospital, which is still operational — now managed not by the state but by Doctors Without Borders (MSF), which is the only international nongovernmental organisation that remains in Batangafo. MSF employs 180 people to keep the hospital running and manages a community health worker programme that provides basic health services to surrounding villages.

When she fled, Soubama took her six grandchildren and five nieces and nephews with her. “You see that small hut behind us,” she says, pointing with derision at a plastic sheet draped over a wooden frame. “That’s my house now. That’s where my whole family lives.”

Women in conflict: agony, misery but that unbelievable strength to carry on

Soubama’s house is one of hundreds of similar structures erected around the hospital, which at one point hosted 16 000 people, all hoping that the presence of MSF would afford some kind of protection. It’s a chaotic scene. As doctors, nurses and patients try to go about their business, they must pick their way past mothers cooking porridge over open fires, young men playing cards to pass the time, bands of giggling children desperate for any diversion, trays of okra drying in the sunshine and heaped piles of furniture and cooking pots, the remaining possessions of the lucky few able to salvage something before being forced from their homes.

“When I heard the gunshots, I ran out of the house and left everything in the house. Then Seleka came and took everything. Here I don’t have anything,” said Soubama. She doesn’t know whether she will ever be able to return home. “Almost all our houses were systematically looted. They broke all the doors. So we ask ourselves: If we go home, where are we going to sleep? With what plates are we going to eat?”

To compound her problems, it is harvest time but Soubama and her family are unable to go to their fields. “If you’re unfortunate enough to meet men when you go into the fields, they can rape you or even kill you and leave your body there in the bush. There are pumpkins that are staying there in the field, peanuts that are staying there and that’s the way it will be. It’s certain there will be hunger later.”

Others in the hospital tend their crops at night, relying on the darkness to keep them safe.

Soubama has no sympathy for either the anti-balaka or the ex-Seleka, but her fiercest criticism is reserved for the government. “Right now, I don’t know if the state exists. The government has forgotten us, there are no military forces to protect us, they have abandoned the population. I hope you will broadcast loudly what I have told you, so all the world can hear about how the people of Batangafo are living. If it doesn’t get better, we will all abandon the town too.”

‘We are replacing the state’

The base of the local anti-balaka leader is just on the outskirts of Batangafo. It’s not much of a base: Commander Bruno Ganassere and his men have simply commandeered a few huts in a village alongside the road. Guards armed with rifles or machine guns are posted on every path into the settlement. Aside from the fighters, perhaps a dozen in all, there are three women and a handful of children sitting under a tree. Otherwise, the village and its surrounds are deserted.

Ganassere is well respected in Batangafo, seen as disciplined and brave. NGOs say he is reasonable, someone they can work with. The 28-year-old is young for a militia leader. Then again, most of his men appear to be a decade younger.

We sit on simple wooden furniture, also commandeered. Speaking from someone else’s chair, outside someone else’s home, Ganassere explains why his militants are the good guys. “The anti-balaka are local, from here. We are not rebels. What pushed us to fight is the behaviour of the Seleka. They are committing atrocities on the population and killing them. We are forced to defend the population.”

Ganassere describes his mission as keeping the peace until such time as the government is able to reassert its authority. “Today there are no police, no army. We are replacing all those institutions that do not exist in Batangafo. If we were not here, the fate of the town would be very bad.”

Another of the fighting groups

Ganassare and his men are Christian, and the ex-Seleka are overwhelmingly Muslim, but Ganassare denies that this is a religious conflict. “It’s not a conflict between Muslim and Christian people. The Muslims mostly support the Seleka, which makes a disagreement, but if the Seleka were not here there would be no trouble,” said the anti-balaka leader.

Nonetheless, he freely admits to punishing Muslims for the crimes of the ex-Seleka. “Very often ex-Seleka go and rob people and steal motorbikes and food. Then we have to react. So when we see a Muslim on a motorbike, we take it and give it back to the people.”

Ganassare says he wants to stop fighting and go back to being a fisherman. He says he is more than willing to disarm — but only if the ex-Seleka militants do so first.

On the other side of town, on another commandeered wooden chair outside another commandeered building, Colonel Djibrine Séïd, an ex-Seleka leader, says much the same thing. Séïd and his top lieutenants are noticeably older and battle-scarred; one boasts a nasty gash on his left bicep and another has a neat dressing on his head where he was grazed by a bullet. The ex-Seleka are also better armed. One militant sleeps under a tree, his rocket-propelled grenade launcher casually propped up next to him.

“We don’t know what God wants to happen. But we want peace. But we are always attacked by the anti-balaka, so violence continues,” says Séïd.

Séïd is Muslim, but he also denies that the conflict has its roots in religion. “I’ve heard the description of this as a fight between Christians and Muslims but it’s false. You can see that, where there is Seleka, there are Christians. But in areas with anti-balaka there are no Muslims, because if they see Muslims they will kill them.”

Séïd lays the blame for the ongoing violence at the anti-balaka’s door. “We wish not to react but how many times can you be pushed without reacting? All Muslims are united to disarm. We are just asking for our rights to be respected.”

The third armed group in Batangafo proper is a contingent of 100-odd Pakistani soldiers, here as part of Minusca, the UN peacekeeping mission. They are the closest thing to a legitimate central authority in Batangafo, but that authority is tenuous at best: the peacekeepers don’t speak the local language and are powerless to prevent violence outside the town’s main roads. (It says something that the only semblance of state authority in this town comes from international actors such as the UN and MSF).

The total absence of government makes peacekeeping in the CAR more difficult than anywhere else in the world, says Lieutenant-Colonel Salman Hassan, the battalion commander. Hassan and his men are based in the old court building, on a rise that overlooks the town. The building is now ringed with barbed wire, and blue-helmeted soldiers man the machine-gun nests that straddle the gate.

Another camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) has sprung up around them, with residents hoping that proximity to the base will keep them safe. The logic doesn’t always hold: several months ago, fighting here forced thousands to flee to the MSF-run hospital — displacing the already displaced. Some, but not all, have returned.

The reality is the peacekeepers are heavily outnumbered by the groups they are meant to control. “In Batangafo, Seleka have about 40 to 50 men. But if something happens, they can mobilise 300 to 400 in a couple of days. The anti-balaka can mobilise about 200 in a couple of days. Both groups have rifles, automatics and rocket-propelled grenade launchers,” said Hassan.

This means the peacekeepers’ main weapon is communication — talking to local leaders, trying to defuse tensions before they get out of hand. Force is supposed to be a last resort, although this runs counter to the instincts of most soldiers. “Keeping the arms in the hand and not using them is like keeping an athlete from running,” observed Hassan.

The fear is that poverty level could worsen

Most people the Mail & Guardian spoke to in Batangafo said the situation would probably be worse without the presence of Minusca. Others, however, were sharply critical, arguing that the peacekeepers are biased in favour of one group or the other. They were also criticised for not intervening boldly enough to protect civilians. Hassan said they were doing their best. “Nobody in the world is ever born who has been ideal,” he said.

‘Maybe it’s too late’

The abandoned Batangafo suburb where Elysabeth Namdanga lives is eerily quiet. Hers is the only family that still lives here. Everyone else has fled. If she could, she would gather up her family — two adult daughters and six grandchildren — and run away too.

Namdanga is old and tired and angry but above all she is terrified. She never sleeps easy. “If I hear gunshots, I’m scared, but I’m trying to suppress the fear because there is nowhere else I can go … I’m always angry when I remember what happened, especially with the leaders of the armed groups who fight and make life difficult for everyone. No one can go to the fields and work. I am very angry with them,” she said, sitting on a bench outside her mud-brick home. The playful screams of her grandchildren echo through the deserted neighbourhood.

Namdanga says she is too old and poor to build a new life for her family anywhere else. “I can’t go to the IDP site because no one will build a hut for me. Also in the IDP site, hygiene is not there. The toilets are far away and I don’t have enough strength to walk all the way to get things, even to go to the toilet.”

The men in Namdanga’s family — stronger and fitter — have left the family home, looking for work and opportunities elsewhere in the country. As ever, it is the most vulnerable who are left to deal with the consequences of the near-complete collapse of authority in Batangafo.

“I’m angry because they kill women, they kill children. We are neutral, and yet they kill us,” said Hèlène Mboiboma, vice-president of the Organisation des femmes centrafricaine. She also was forced to abandon her home and has ended up in Batangafo hospital with her five children.

“Really, women have suffered. Suffered. Many women were killed. Us women are innocent in this business,” she said. How different things might have been, she suggests, if women had been in charge. “Women don’t want to fight. We want peace. Who is taking care of the kids when the men are fighting?”

Mboiboma wants to go home, to her house and to her crops, but she’s still too scared. And she doesn’t see that changing any time soon. “I’ll go home when I don’t see armed men in Batangafo. When there are no weapons and I don’t hear gunshots.”

Back at the mosque, Imam Abu Yusuf is still mourning all that Batangafo has lost. “The picture is a bit dark,” he says. “This town is not holding together. Maybe it’s too late.”