Northern Nigeria: Humpty Dumpty Or Behemoth in the Pangs of Transformation?

Walking away from imprisonment in grand narratives and black boxes, a concept such as northern Nigeria stares everyone in the face. Because, one very important question in Nigeria today must be whether Boko Haram is a case of unforgivable intelligence failure or mind boggling poverty of political leadership. In other words, how did it happen that the country could be swallowed up by violence of that magnitude without it being predicted and contained by those paid to do so? Now, it is a wasteful pastime posing such a question because it is beyond the folks to know what the intelligence community gave or did not give to the political leadership. Or, what the political leadership suspected and put the intelligence agencies to. Or, even what the civil society itself figured out and demanded of both the political leadership and the intelligence or security agencies. After all, there were people outside the country who knew and, at no cost to Nigeria, made it media stuff that trouble was heading in the direction of the African giant in the form of a targeted destruction of the country. Everyone read it but went to sleep instead of the kind of spontaneous street actions in defence of homeland that would have been the case elsewhere. It turned a classic of cutting one’s nose to spite one’s face because, notwithstanding the much talked about centralizing and decentralizing tendency of federalism in Nigeria, trouble anywhere in Nigeria leaves no one unaffected.

It could be that Nigeria does not have her own experts on politics of the northern space and national security, the national security implications of environmental crisis in the Niger Delta beyond resource control insurgency, a national security imaginary on the Atlantic Ocean, for instance and so on. Thus left with traditional security analysts, it failed the test by focusing on what security is rather than what security does. There is, therefore, cause to ask whether northern Nigeria is now a case of Humpty Dumpty which all the King’s horses and all the King’s men could no longer save after a great fall or it is that of a behemoth in the pangs of transformation. It cannot be both simultaneously. Which is which?

A yesterday headline that speaks to today

Seven key developments are frightening about contemporary northern Nigeria. One of it is the situation today whereby the region will remain the nightmare for students and practitioners of violence prevention, conflict transformation and post conflict peace building. This is irrespective of whichever shape Nigeria assumes in the foreseeable future. It could be said that inter-group violence is the only thing that has thrived and consistently so across the region for the past 36 years. Since the Kasua Magani clash in Kaduna State in 1981, the region has moved from one such discord to another. With the exception of Sokoto (which recorded only one case of violence relating to tussle over the Sultanate) and perhaps Kebbi, every other state in the north has had its own share, with Kano, Plateau and now Borno, Kaduna and Benue becoming the leading theatres. Benue’s is in a different category, being of herdsmen violence nature, some of whom are even from outside the country. So far, ethnicity and religion provide the sparks for conflict even as the class division is no less volatile, in both the Christian and Muslim dominated areas.

Closely tied to conflict is the crisis of pluralism in the north. Notwithstanding the razor sharp religious and ethnic differences, the north is compacted in such a way that de-mixing the population as a way of securing peace is out of the question. It is only in a few far northern states such as Jigawa, Kebbi, Zamfara and Katsina that indigenous Christian populations might not be that substantial. This is not the case in the rest. Moving down into the middle belt section of the region, states such as Kogi, Nasarawa, Plateau and Kaduna (again) present a mixture as to complicate religious, linguistic, cultural, spatial or political operationalisation of the concept of middle belt even as its activists understand the notional boundaries. In other words, the north is not just pluralistic, it is naturally compacted in a way that de-mixing as a conflict management approach cannot even be considered. It gets even more complicated when it touches on non-northerners. There are virtually no northern cities without substantial concentration of Igbos, Yorubas, Binis, Ibibio, Ishekiris, Urhobos, Kalabaris, Ijaws and so on.

On this count, no other region in Nigeria has the complexity that the north has. The nearest to it is the south-south but whose is restricted to the cultural and linguistic differences, not religion. That makes that place more manageable than the north. The south-west has religious diversity but same cultural root would appear to provide the counter for that, if not the powerful Awo political personality shield. So, the north is the unique spectre from which there is no easy walk away in conflict management

The third is the north’s uniqueness in underdevelopment, to the point of tasking development strategists and practitioners. There is none of the three geo-political zones in the north that does not score the lowest hits on any item in the Human Development Index. With pupils receiving lessons on the bare floor a common feature, with the figures of Vesicovaginal Fistula, with dismal figures of school enrollment, with WAEC/NECO results, no statistics are needed to prove any claims here. To those three features is a fourth. In spite of the length of time the region has controlled power at the centre, it is not in control of any sector of the economy, not to talk of control of any of the commanding heights of the economy. It is not even there in agriculture where it had the comparative advantage. There used to be a debate within the radical circuit about achievability of radical change in Nigeria without specifying the bourgeoisie in terms of the locational characteristics. Today, such a debate would be meaningless because the so-called northern oligarchy has taken an exit. With the uninspiring performance of the Buhari regime, the ‘Kaduna mafia’ too has followed while the ‘Langtang mafia’ is in a dreadful quietude.

The third is the north’s uniqueness in underdevelopment, to the point of tasking development strategists and practitioners. There is none of the three geo-political zones in the north that does not score the lowest hits on any item in the Human Development Index. With pupils receiving lessons on the bare floor a common feature, with the figures of Vesicovaginal Fistula, with dismal figures of school enrollment, with WAEC/NECO results, no statistics are needed to prove any claims here. To those three features is a fourth. In spite of the length of time the region has controlled power at the centre, it is not in control of any sector of the economy, not to talk of control of any of the commanding heights of the economy. It is not even there in agriculture where it had the comparative advantage. There used to be a debate within the radical circuit about achievability of radical change in Nigeria without specifying the bourgeoisie in terms of the locational characteristics. Today, such a debate would be meaningless because the so-called northern oligarchy has taken an exit. With the uninspiring performance of the Buhari regime, the ‘Kaduna mafia’ too has followed while the ‘Langtang mafia’ is in a dreadful quietude.

The fifth point in the checklist is how the north blows every opportunity it has to elect someone who could be good for the north as well as for Nigeria. It lost out in Umaru Yar’Adua and President Buhari is basically a lame duck now. Many would disagree that he is a lame duck because of health challenges. No health challenge will be such a strange thing for someone at 74. What have dealt severe blows on the Buhari promise is coming to power without a development strategy and then worsening that with a cabinet at war with itself. Without doubting the possibility of the president making a statement on reflexivity, everything might already have been lost, what with half the tenure gone and re-composition of the very exclusionary cabinet slow in coming, if coming at all. Yet, he is exercising the northern quota.

There is a sixth point in how, apart from the social mobilisation initiated by politicians such as the late Mallam Aminu Kano, Aminu Kano, Joseph Tarka and the Borno Youth Movement in the late 1950, there have been no other such region wide exercise. In short, nowhere in the region has experienced any such mobilisation around any core value worth dying for since then. Since the earlier such exercises died with the 1966 coup, it means the only menu the northern folks have been offered is region and religion. As the region is, however, divided along religious and cultural identities, religious and regional mobilisations have produced divisive orientations that have now gone out of control. It is not as if the elite in the southern part of the country were better than their counterparts in the north in the politics of mass conscientisation even as someone such as Chief Awolowo made Socialism respectable and acceptable in Yorubaland by arguing that it is not synonymous with poverty. The difference, however, is that there is an elite mobilisational agenda in its inherent acceptance and even adoration of education as a social necessity for everyone unlike in the north where children of kings were the exclusive beneficiaries for so long.

Gen Gowon,

Gen Murtala Mohammed

IBB and Gen Abacha

The seventh and last point which is really where the tragedy of the north lies is in the north being the zone of origin of many of Nigeria’s leaders for close to forty years but with nearly nothing to show for it, development wise. This is borne out by the above list: the lack of conscientisation, the extreme poverty, a heritage of violent inter-group relations, missed opportunity for change through electoral instrumentalism and a total exclusion from control of the economy by any fraction of the bourgeoisie from the region which has produced more leaders at the centre than any other. Is it the case that leaders of Nigeria from the region were always so altruistic that taking care of their region was an anathema or they were never clear of the utility of power, a point which Chief Obafemi Awolowo is the unbeatable model in its demonstration.

Chief Awolowo never became President or Prime Minister or Head of Interim Government or Head of State of Nigeria. The highest he went was Vice-Chairman of the Federal Executive Council. In other words, he was simply a very senior minister, nothing more. Yet, the Yorubas enjoy a very high consciousness of and attainment of educational advancement in Nigeria; higher income per capita; relatively better health infrastructure even if that might have been concentrated around Lagos; higher standard of living and better placement in just about every other item in the Human Development Index. The temptation to ascribe ethnicity to him would not be sufficient explanation for this accomplishment because there is also something called the utilities of power, of which empowerment of the people is a key item. Without empowerment, prosperity within a polity is impaired and government or leadership or state power becomes an aimless project. The Sardauna was doing something in this direction but nobody emerged with his radius afterwards.

Everything else in the world revolves around power. The Leninist wisdom is that power trumps economics. If he were still alive today, he would have certainly amended it to ‘power trumps everything else’. But here is a situation where power itself is trumped. The north is basically still in the state of nature, with what is going in the north east, Southern Kaduna, Benue State and, to a lesser degree, rural banditry in Zamfara State. What is the logic that informs exercise of power when a northerner rules Nigeria, with particular reference to what the northerners get without cheating the other regions? What conception of power drives acquisition and deployment of power by Nigerian leaders of northern origin?

It is true the Ibrahim Babangida regime managed to build Abuja. It is something for which he and his ideologues deserve to be congratulated, no matter the imperfections. Such would be warranted by the fact that Abuja is for all Nigerians. It has a unifying import in itself. Its magnificence also challenges the cultural imagination that interrogates the state building capacity of Africans. However, when deconstructed in terms of who owns what in Abuja, it would be found that the share of northerners would be the least. Even the Igbos who lost the war would be found to be far, far ahead.

All these could have been taken as a case of very altruistic set of leaders who do not know how to favour their own area of origin, perhaps because such would be to the disadvantage of other parts of Nigeria. But, as indicated earlier on, northerners in power justified it in terms of northern share of the national cake. If at the end of the day, northerners cannot see any pieces of the cake, then something has gone wrong somewhere. It is more so if ignorance is combining with poverty to make the north ungovernable.

When one looks at the regional ownership and control of banks, it is even worse. Meanwhile, as in access to ownership of Abuja, all the second generation banks were born under one Nigerian leader or another from the north. It is understood that when the Obasanjo regime extended the deadline for recapitalisation in the case of the defunct Bank of the North, the north let it slip by. Today, the region has not even a single bank. Yet, it is banks that give credit and, therefore, determine investment. Is it not a wonderland project to expect the region to develop even when the region does not have a single bank it controls?

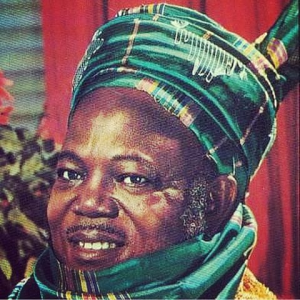

Sir Ahmadu Bello, the late Sardauna of Sokoto: Now generally acknowledged to be far more broadminded than his own political children

Again, the story is worse in the case of the universities. Universities in Nigeria have been generally on a downward swing since the SAP reified itself in that realm in the early 1990s. Here, nobody expects a Nigerian president to single out universities in the north for special favours. What would have, however, been exemplary leadership is acting out exactly what the Sardauna did in his days. And what did he do? He ensured a strict merit system in general and in the lone university of his time – Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. It was on that foundation that that university climbed and made a global statement as an academic centre. If the truth be told, is ABU of today in anyway comparable to ABU of yester years? And why is it a case of decline rather than rise to higher stature? The north could not insulate ABU, Zaria from the chaos that has characterised the region in the past few decades. It reached a point where students were even manipulated to slug it out on religious test of strength on the campus. How could it become so necessary for anybody to provoke religious violence among impressive young people who had yet to encounter the world? Yet, the north did it. It happened in the north, with all the leaders – traditional, business, political, military and religious – looking. Now, some of these same students might as well be the local commanders of skull cracking squads in the so-called religious riots common across the north in the past few decades. How could a society deliberately set itself up?

The question, however, is whether all these frightening features of the north now mark Humpty Dumpty’s demise or are the pangs of a Behemoth in transit from backwardness eventually to something closer to modernising. The second part of this report would attempt an answer by looking at what might be considered the silver linings. What are those and how might they be silver linings?