Rebuilding the House of Eve: Reinventing the Feminist Agenda in Nigeria (Part 2)

By Chom Bagu

In the second and final installment of the emergent canonical text on gender politics in Nigeria, Chom Bagu outlines the specifics of the ‘What is to be Done’ poser, prefaced with another look at the history of the gender movement and its key warriors. The bibliography has been edited out for obvious reasons but those who might need it could get from either the presenter or Ene Ede @ Search for Common Ground or, Intervention – Editor

History of Gender Activism in Nigeria

Could these answers come from the history of gender activism in Nigeria? In the recent history of women activism in this country, five phases can easily be identified:

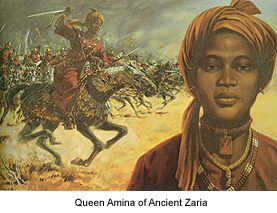

Queen Amina of Zazzau

- The heroic age which predates colonialism when women like Queen Amina of Zazzau and Moremi of Ife among others smashed the patriarchal glass-ceiling to assume leadership positions in their male dominated communities.

- Anti-colonial era which saw women as individuals and groups protesting colonial exploitation and oppression and mobilizing for an end to colonialism. These women included Funmilayo Kuti, Gambo Sawaba and Margaret Ekpo among others and the groups that emerged include the Aba women and others in 1929 and the National Women’s Union in 1953, etc. (see ‘Nigerian Women Mobilized’ by Nina Mba).

-

Queen Moremi of Ife in her University of Ife memorialisation in a hall of residence

The Independence era where women like Sawaba, Funmilayo kuti and Margaret Ekpo as a result of their contributions to the struggle for gender equity on the drive to independence, secured spaces to represent women in the various progressive political parties and groups like the National Council for Nigerian Citizens (NCNC) and the Northern Elements Progressive Union (NEPU). The main outcome of these gender struggles was the establishment of the National Council of Women Societies (NCWS) in the1959. The NCWS unfortunately came under the influence and control of government and the post-independence governing class there by undermining its independence.

Fumilayo Kuti and famous son, Fela

- Social movementism that started emerging in the late 19970s and culminated in the establishment of Women in Nigeria (WIN) in 1983. The era of pragmatism started in the late 1980s and matured in the mid 1990s. The root of this pragmatism was “first ladyism” and the pet projects that became the hallmark of this era (See Jibo Ibrahim’s The First Lady Syndrome). This mode of activism was reinforced and blossomed during the June 12 struggle when donor money flooded the country and the devastated middle class seized the opportunity to establish portfolio CSOs as a means of securing better ways to earn a living (what we call “neman abinchi”). Women groups at this time abandoned the larger vision of women liberation and focused more on implementing “women projects.” As a consequence, tokenism and patriarchy reasserted themselves with even greater force under a cacophony of noisy gender lingo.

Analysis

Analysis

An analysis of all these phases of feminist activism shows that, apart from the first and the fourth, where women took the initiative and were in control of their processes and programs, women during the three other phases were to a certain degree responding or reacting to other group’s actions without any self organizing principle. Many say the Aba women were an exception. The problem with the Aba women protest, however, was that it lacked strategic vision beyond the protest.

In the heroic phase, these women who became leaders in their communities did so through individual prowess, ingenuity or effort. They were able to understand the political environment of their time and as a result of either unique gifts or opportunities, they positioned themselves and seized the opportunities they had to take over leadership. Though these were episodic occurrences, it at least demonstrated women’s capacity for successful leadership and organization.

In the case of WIN, its founding came at a time when the ideological movement in Nigeria had matured and had become very gender sensitive. The fledging women movement then located itself within the ideological movement and took advantage of its structures to grow and spread across the country. It served as a fresh wind that blew across the feminist movement then dominated by the NCWS, then a semi-governmental body of elite women re-echoing government voice at every turn. The entry of WIN for the first time showed that gender equity was not a cause for only women as it allowed male membership and forged alliances with progressive male dominated organizations. This is what made WIN a social movement and not just a feminist group. The Woman Question was posed not as the replacement of male and patriarchic oppression with female or matriarchic oppression, but as a social problem that needed to be resolved so that Nigerian society can become whole again.

In the case of WIN, its founding came at a time when the ideological movement in Nigeria had matured and had become very gender sensitive. The fledging women movement then located itself within the ideological movement and took advantage of its structures to grow and spread across the country. It served as a fresh wind that blew across the feminist movement then dominated by the NCWS, then a semi-governmental body of elite women re-echoing government voice at every turn. The entry of WIN for the first time showed that gender equity was not a cause for only women as it allowed male membership and forged alliances with progressive male dominated organizations. This is what made WIN a social movement and not just a feminist group. The Woman Question was posed not as the replacement of male and patriarchic oppression with female or matriarchic oppression, but as a social problem that needed to be resolved so that Nigerian society can become whole again.

Margreath Ekpo

The second set of phases which took the mode of WID (i.e., Women in Development. Please see Charmaine Pereira’s paper on feminist Knowledge) shows that the women movement flowed with the political current without any autonomous agenda, found roles for itself in the process without any self organizing principle or self articulated vision or strategic plan. The women in the anti-colonial, independence and pragmatic periods in spite of the hard struggles they waged and the language the used, these struggles were mere appendages of other struggles. They women were only protesting and not fundamentally challenging the foundation of patriarchal society. They allied themselves to the institutions of patriarchy in the hope of getting some crumbs or some little consideration.

Between 1993 and 1999, as a result of the June 12 struggle, several women groups and coalitions were established to fight for democracy and the end of military rule and to extend human rights to women. With landmark event like the passage of CEDAW, the Beijing Conference and the increase in the raping of women in communities like Umuchen, Odi, Zaki Biam, etc, the quality of women activism was expected to increase. Reuben Abati (of the Guardian newspapers) has shown that while women acquired a stronger voice, this voice did not result into a more qualitative struggle as the result of the 1999 elections shows. The political agenda for Nigerian women which was launched in the pre-999 period hinged the fate of the feminist struggle on affirmative action that would give women 30% of political offices. This did increase the proportional representation of women in politics and public life, but failed to change the lot of women in any meaningful way as our earlier quotation indicates.

Aisha Buhari, Nigeria’s incumbent First Lady

The assumption that the more women get to positions of power, the more empowered they would be to influence policies and determine the destiny of women did not prove quite correct. Even if these women in public life were to have influence on policy, what policies are they to support? With no vision or mission of their own to inform their politics, women who found themselves in positions of power only feathered their nests and little else. Affirmative action has therefore become a weapon of patriarchy to invited elite women to “come and eat.” (apologies to late Afolabi). But even the elite women have not had an easy time as they have been plagued by numerous problems exemplified by the removal of the 1999-2003 speaker of the Benue State House of Assembly and the travails of the former deputy governor of Lagos State (see the account of what 19 years of first ladyism in Ghana did the feminist movement in Jibrin Ibrahim’s paper on the same theme). The point here is that the politics of affirmative action when lacking in content or an all embracing vision, cannot lead to transformative changes in the fortunes of Nigerian women.

What all this means is that unless women organize in their own name, develop a vision and an action plan on which they select their best representatives to represent in what positions, platforms to struggle for their issues and networks to support them, they will remain marginalized and dis-empowered whatever the degree of affirmative action.

Options

Options

So, if we want to rejuvenate the feminist ideology in the way we talked about at the March 8, meeting, we need to find out why religious/ethnic fanaticism and football hooliganism, both patriarchal spheres, are the only social phenomena that attract public passions. Can we do what is needed to create the same passion?

For religious fundamentalism, the crisis that has engulfed the world economy and politics, the HIV/AIDS pandemic and the social crisis that has created quantum uncertainty and insecurity have made religion the only remaining refuge for the vast and poor populations of the world who are literarily drowning. Festooned by big money, some from dubious sources that pay for streams of furious and bombastic advertisement, the new religious movements have succeeded in creating a religious euphoria through feeding on fear and greed. Ethnic fundamentalism has also been able to take advantage of such passions to launch genocidal campaigns.

Sports particularly football is also feeding on the same fear and big gambling money. The furious competition and display of macho that sports and football engender find emotional support from fear and the deep needs of the poor and powerless to who are seeking ways to sustain the illusions of physical strength in a situation where they have lost all power to manage their lives. The gambling fiefdoms have also taken advantage of this to pump big money into advertisement to keep up the hip.

Both sport euphoria and religion/ethnic fundamentalism have also served the global ruling class as a means of diverting the restless and angry poor populations of the world particularly the youth from fighting for change by channeling their energies and attention to what somebody has termed “induced emotional fast foods.” The strategy is for the poor to be divided into opposing groups on the basis of religion, ethnicity or competitive football and set upon each other. As a result, issues of development and political accountability are not given adequate attention if at all. In all these spheres, competition is central and issues are posed in terms of victory and defeat. The divide is sharp and the passion is often deadly.

Can and is Feminism ready to create such a public passion and can it or is it ready to source for the necessary resources to pay for the media blitz that will keep Feminism permanently in the minds of people? To take that road, Feminism will need to find a message that would create the necessary environment. As we have seen above, the domination of the public space is through exploitation of public fear and greed. Which fear will Feminism feed on? Male domination, patriarchy, or what? It is for us to make the choice. We may need however to heed a wise saying that advises that “From passion arises sorrow and from passion arises fear. If a man (add woman) is free from passion, he is free from fear and sorrow. From the above analysis, the options we have really are either to build the new feminist movement on the passion of greed and fear or on the principle of “no individual person is free, until all people are free.” The option of passion will have to raise tempers and sharply divide people and communities and use the force of blackmail and threat to get people to allow women their rights. This can be achieved through mastering and buying into the power of the media through which we can feed on fear which we will generate among supporters of patriarchy and greed among women about the power and benefits they will get in when women are free, to drive our message.

The second option of ‘none or all’ is to engage the society and make the program of women liberation and gender equity a social challenge where all have a stake. There is need to show that without gender equity and women empowerment, Nigerian society cannot achieve it development and stability goals. This approach will need a different strategy. Here we will have to engage in social mobilization and advocacy using the instrumentality of positive activism where we demonstrate to people the value of gender equality for the over all good of society. In addressing different constituencies, we have to understand where they stand on gender and take the struggle from there. When we struggle for legislation, we do it in a way that it lays the social foundation for full implementation as well as pressure government and other development partners to address the underlying causes of women oppression and marginalization through critical action research and advocacy.

This strategy is not ‘turning the other cheek’ as some are quick to say, but is a strategy of ‘taking the enemy whole’, by understanding that people do things for reasons that make sense to them and to change them, we must create a new understanding and find alternative ways for them to achieve their goals without oppression and disempowerment of women. This will not mean that we will avoid fisticuffs with die-hard chauvinists and those who directly and consciously benefit from women oppression and marginalization. These groups will have to be alienated, isolated and rendered ineffective. In effect therefore, we will use a bit of each strategy depending on analysis situ.

What is Feasible?

Chom Bagu being engaged by journalists, perhaps on what is to be done

Drawing from the above, the reality of Nigeria and the experience of women activism, the feasible is a movement that takes up from where WIN left. The first step is to accept the reality of the present pragmatism and then build in a vision, pro-activity and a political advocacy strategy. The program of such a movement is to give visionary and strategic leadership to the feminist movement by bringing focus to catalytic legislation and policies that address the underlying causes of women oppression, open greater opportunities and provide great empowerment to women. By helping to build synergy in the existing groups, conducting participatory action research, monitoring and evaluation of gender related struggles and building up the capacity of women groups to deal with emerging issues, we will give feminism a new boost and the movement some coherence and stamina.

An action plan in this line will include:

Feminism: At the ACTIONAID meeting Ojobo identified about 19 definition of feminism and in fact said there are about 30 in all. Looking at most of these definitions one can see a lot of duplications and hair splitting. The new organization would need to adopt or coin its own definition that suit its strategy and that will galvanize its constituencies into action. I believe a well facilitated retreat of carefully selected prospective members early in the process could work on this and a few other issues.

In their book “Empowerment”, David Gershon and Gail Straub, suggest “that to create a new reality, you begin by becoming quiet and walking in your mind into the situation as you wish it to be without any constraints.” This is the only way to create a powerful vision. This vision is necessary particularly now that women organizations are engulfed in doing a thousand and one practical projects. To break this pragmatism, we need to buy into what a Japanese proverb advices, that, “Action without vision is a nightmare; Vision without action is a daydream.”

This is so because feminism in Nigeria has had a checkered history and has not been able to articulate a united and coherent creed which it can be easily identified with. Using the power of several minds working in concert, we may come with something original and wipe off the loud propaganda that Nigerian feminists are copy cats of western cultural imperialism and stop any attempt of being branded and put on the defensive. We need a coinage that will provide a powerful vision and appeal to all genuine gender activists and that captures the work that we intend to be doing.

Constitution: Towards the end of the WIN experience, people became more concern with constitutional details largely because they had lost the spirit of the movement and needed guidance by rules rather than principles and values. We must therefore be careful to develop a constitution that inspire people rather than restrict them, that compensate good gender practice than punish so-called rule breaking. We need to consciously adopt a program of membership on the basis of the principles and values that we intend to uphold and then nurture members deliberately in those principles and values through training, joint experiential practice and mentoring. It is in this way that a constitution will come to life and serve as a building block of the organization.

Also key to sustainability, the proposed organization needs to make provision in its Constitution for a conflict management strategy that accepts in principle the inevitability of conflict and provides for healthy ways of working with conflict. It is important to do so because gender work is conflict ridden and an organization focused on bringing about gender justice most develop a strong conflict living and conflict management strategy not only for internal organizational cohesion but also as best practices for the public at large. Dealing with conflict is essential because crisis always serves as an excuse for gender oppression and violence against women and the proposed organization must strive to model best practices and be seen to walk its talk.

Logo: We also need a powerful visual logo, something that arrests attention and helps to bring recognition and goodwill to the organization. Rituals: We need to invent and practice rituals that reinforce our principles and values and remind us to keep faith. WIN tried to do it but ended up merely talking about such rituals. We must model gender best practices and embed it in our lives and daily practice. This is how we will be able to “shine in people’s eyes.”

Communication: Closely associated with this is the need to find or develop a powerful means of presenting and backing up our messages like theatre, poetry, songs or a particular mode of activity facilitation that stand us out.

Advocacy: The approach to advocacy has change from the declaratory, noisy and aggressive posturing used by right-wing pro-Nazi groups to models that talk to the heart, that seek to change perceptions, attitudes and behavior through subtle processes or activity based schemata or transformative experiencing.

These modes of advocacy have to be created by us. Given the scale of advocacy we would be engaged, we need to study what is known as social advocacy and social movementism and see how we can used it to reach all groups and critical stakeholders.

Conclusion

Let me conclude that this is a mere rapid assessment based on my experience in WIN and not a researched paper. It is intended to provide a basis for discussion and nothing else. Having said that, it is important to recognize, as I have tried to show above, that these are times of rapid changes when ideas are fluid and principles difficult to hold over time. This has made it very tasking to create and sustain organizations particularly those that try to go against the grain. Just like paddling upstream, you need double the energy and the effort with no guarantee of success.

As hinted above, our situation is made more daunting by the fact that there are hundreds of organizations out there claiming to be working for gender empowerment. To create an organization that will make the required impact, will need a deliberate approach in the selection of members, processes and partnership backed with hard work. This, I believe is the only road to success.

As necessary first steps, I will advice extensive and wide consultation with all stakeholders and a more detailed research on some of the contentious issues. For, to undertake this historic journey, we must take every step on the basis of existing knowledge and tested experience.