Back to Presidential Health Politics in Nigeria

Coming shortly after a Lagos lawyer’s recent claim that President Muhammadu Buhari is so sick as to have sublet his mandate to a cabal, the president’s departure for medical attention in the United Kingdom late last week is bound to keep Nigeria’s centres of power awake all night long until his return and resumption. Curiosity about details of what the president’s ailment is and how he fares in the UK is bound to remain high except that very few expected it would reach the level of yesterday’s rumors of his death, a rumor strong enough as for the Presidency to respond to it. Whether a direct refutation was the correct information management tactic is open to debate. And whether it justified two well heeled professionals speaking on one and the same issue for one and a same president of one and the same country is equally a different matter.

Femi Adesina, Presidential spokesperson

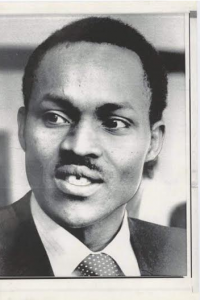

Garba Shehu, Presidential spokesperson

What is not debatable is how this round of rumors and counter rumors has brought back memories of the tension and suspense that attended the late President Umaru Yar’Adua’s sickness and death in 2010. As things are now, even if President Buhari were to catch ordinary cold from staying out late yesterday with First Lady, it risks being seen as a close call to death. Such would not so much indicate that everyone wishes the president ill. It is that late President Umaru Yar’Adua’s case has taught the lesson that the management of the president’s sickness in a country such as Nigeria which is irritated by standard way of doing things can become a problem in itself.

At stake is the power sharing arrangement which legitimates presidential power in Nigeria more than the formal provisions about that office. In other words, the president getting sick in Nigeria automatically becomes such a complicated issue because anything happening to an incumbent ruptures the regional turn – by – turn in accessing power. The region from where such incumbent comes from becomes the loser in terms of its allocation of eight years in power. The region which produced such an incumbent’s Vice-President gains a bonus in accordance with the constitutional provision which stipulates the Vice-President as the inheritor of the Office of the president should he or she become indisposed, incapacitated, impeached, resigns or dies. If any such thing happened, then there has been a providential annulment of the power sharing formula at that moment in such a way that no one can do anything about.

A much younger and obviously healthier Buhari

Late President Umaru Yar’Adua

The wise men and women who crafted the resolution on the rotation of power principle at the 1995 Political Conference anticipated that an incumbent president could become indisposed, incapacitated, resign or be impeached, any of which jeopardises the arrangement as the region where such an incumbent came from would have lost out. So, they provided for succession in such circumstance by restricting the successor to a particular Vice-President. The men in khaki who succeeded Abacha took that provision out along with the main provision itself. That is why today, an incumbent president falling sick in Nigeria is such a big source of tension.

That has not stopped presidents from falling sick. Umaru Yar’Adua came in 2007 already sick. He died eventually in 2010. When that happened, the north was split on how best to respond to it. One dominant camp suggested the north withdrew from the scene and took the next four years to reorganise itself, with particular reference to searching for a presidential candidate who could reconcile and unify the north as well as serve Nigeria. This camp wanted the north to accept the death of Yar’Adua as God’s intervention in the rotation of power principle, another way of saying Goodluck Jonathan, Yar’Adua’s Vice, be given free rein in 2011. The other camp argued for a northern consensus candidate who could beat Goodluck Jonathan with a solid regional block vote and a sprinkle gathered from other parts of Nigeria. There was no consensus but the first problem with the northern consensus candidate strategy was that two prominent northerners, IBB and Atiku Abubakar, wanted the job. The committee set up to screen these two came up with Atiku Abubakar as the consensus candidate of the north. The criteria used were not too transparently displayed. It is obvious the idea of having another General in power must have worked against IBB. But then Atiku ended poorly in the PDP Presidential Primary, losing it even in the north east where he comes from. That weakened any reference to having been rigged out, much as that could have been the case. Having won the PDP Presidential Primary, the result of the election itself was a foregone conclusion in favour of Jonathan. The split in the north was deep, stretching from historical fault lines to party and intra-party as well as religious contours. The post election violence that greeted the results of the elections in April 2011 was quite revealing about this.

By 2015, the retired military as a factor in politics, elements of Obasanjo’s own calculations about presidential power, assumption or sentiments that a General would better deal with Boko Haram, improved electoral management and related factors tilted victory to General Buhari at last after three previous attempts. For ill health to become part of the same Buhari within the first year of victory leaves many people wondering if those who should have thought deeply about Buhari’s candidature did so. While it would be very rare to find a perfectly healthy person at Buhari’s age, that is not the same with what appears to be the case at hand. If Yar’Adua’s was a mistake, why would the same mistake appear to be the case again?

To be president of Nigeria is ordinarily stressful for even a younger person. It cannot be otherwise in a country in which even the most sophisticated members of the elite make no distinction between the right to criticise the government of the day with the self-given right to rubbish the state, all in the name of anger. All such irregular patterns of citizenship can unnerve any president, particularly a president who is over 70 and had, additionally, been a military officer. The rigours of military professionalism certainly make a 70 year old retired military officer older than one who was never in the military.

But beyond Buhari, it is Nigeria’s lethargy in crisis management that might be more at stake. There is no reason which justifies allowing a cycle of tension as this to continue. Doing so is a necessary dimension of the rotation principle because even a young and supposedly healthy president could still die anytime just as an old and sickly president could end up living longer. Why is the country still shy about legalising the rotation of power principle after it has become too glaring that it is such a vital national security ingredient? It is either it is legalised or a party/politician is bold enough to campaign against rotation of power as the late Abubakar Rimi did in 1998. He said the rotation principle was not progressive and he did not need need zoning to win. How far he would have gone in a post June 12 Nigeria is now a matter for speculation. Could it be that the country simply doesn’t have such self-confident politicians anymore?