Reloading Nigeria’s Risk Baggage in 2017, (Part 2)

In Part 1 of this Special Report, Intervention discussed three out of the seven sources of Nigeria’s risk baggage it considers troubling in 2017. These were the Crisis of National Self-Understanding; the Rising Elite Fragmentation and the ‘Iron Law of Oligarchy’ in Nigeria and Cabalistic Entrapment and the Unscrambling of the Buhari Promise. In this second part, it is discussing three more. These are the Demise of the Left in Nigerian Politics; the Decentering of the State and the Mismanagement of Anarchy and ‘Oil and Instability’. The last segment and the conclusion will follow tomorrow – Editor.

The Demise of the Left and the Gap

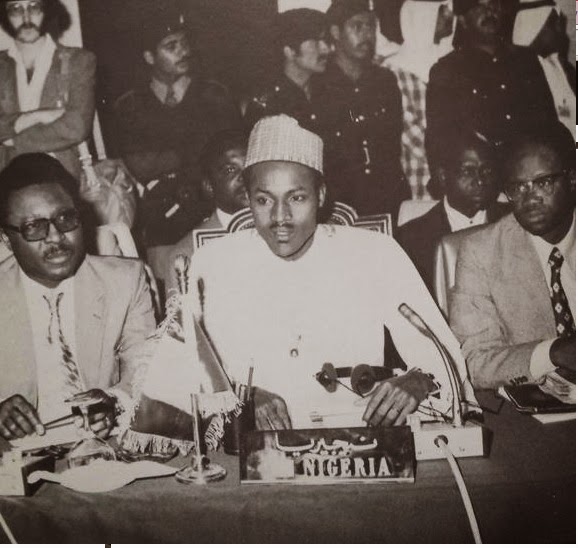

One story line here!

The late Chima Ubani

The left force in Nigeria was so broad a church on which no one ideological strand was definitive of. But it spoke the collective language of ‘emancipation’, be it the old NANS strand, the now dead Women in Nigeria, (WIN), the defunct Campaign for Democracy, (CD), its successor – the Democratic Alternative, (DA), the Academic Staff Union of Universities, (ASUU) and, of course, the Nigeria Labour Congress, (NLC). Wherever they were, be it in the newspaper houses, academia, the professions and even in politics or business, the leftists shared a clarity that distinguished their voice and made their standpoint the object of adulation or hatred. In the wake of the imposition of SAP in 1986, they led the discursive assault that exposed the programmatic baggage of the experiment with human beings. The military regime naturally took them head on, first by targeting the universities, labour and the media. Universities were the theatre for the discourses that empowered the street actions. They, therefore, infuriated the junta.

By the early 1990s, the left had been crushed. A recent book calls it the implosion of the left but from the angle of how June 12 led to that. The defunct National Association of Nigerian Students, (NANS), was the first to collapse when its leadership was successfully taken over by ‘Sergeant Doe’ leaders. That leadership is the origin of the current culture of NANS living on handout from ministers or government departments; the culture of holding NANS functions in Five-Star hotels and the NANS President maintaining Special Advisers and Personal Assistants. It simply shows how some people had missed their way into what they had not been prepared for. After NANS, CD followed, then WIN. Labour which was so patriotic and radical had been the first to be taken over and a leadership imposed. Very gradually, Nigeria became a monologue of its establishment and even then, an establishment confronting its own incoherence and speaking the language of self doubt and division to the country.

Very recently, General Obasanjo, for instance, admitted that Nigeria has never been this fragmented. That level of fragmentation would never have been possible if the left was not successfully destroyed, a process in which the Nigerian State was the single most important actor. The Nigerian left never spoke the language of insularity. All its own debates as well as those conducted by people who were broadly aligned to it spoke to nation building. No issue was beyond its comprehension as can be seen from how they tackled the national question, for instance. A study of the communiqué of the major civil society platforms between 1985 and 1993 will show this clearly. Nothing is happening today that those communiqués did not warn against.

By the time Chima Ubani died in 2005 was also the time the left also finally gave up the ghost. This is in the sense that the comrades who went for the burial left with a horrifying notification of how far down Nigeria had gone. Biafranists would not allow a comradely burial for a Chima who never shared and never spoke about Biafra for one second in his life time. Today, the Biafranist momentum has moved up from confronting Chima Ubani’s comrades on how to bury him to confronting the Nigerian State and the establishment does not appear to have an idea of managing what they have called to being by deliberately decapitating left politics and closing that space for leadership grooming. The student movement was absolutely harmless beyond fabrications by those looking for budgetary concessions. Now, the space they left have been taken over by another set of activists of insurgent instincts mobilising religious, regional, resource and ethnic violence.

The Decentering of the State and the Mismanagement of Anarchy

In its study of violent conflicts in Nigeria since 2001 in particular, the Institute of Governance and Social Research, (IGSR) concluded that the conflicts were such that set neighbours, ethnic and religious groups against one another in violence in which all accepted rules of war were observed in breach. That is accepted rules of war such as not targeting civilians, women and infants. In traditional Political Science, that is what is called anarchy or ‘the state of nature’, a jungle encased by the war of all against all and where it was about the survival of the fittest. It was that situation that the state emerged as a response to save us from ourselves through exchange of our loyalty for its protection. Henceforth, the state was granted the monopoly of legitimate use of violence. So, anarchy is a serious indictment of the state in whose jurisdiction it takes place. Anarchy in Nigeria since 2001 tells us that the Nigerian state has been a sick state, not dead but neither functioning.

There is a Nigerian dimension to the crisis of state in Nigeria. Generally, however, the very idea of the state has been in trouble since the end of the Cold War. At no time is the state challenged on all fronts as since 1991. The world watched as states collapsed or were confronted with superior violence and overwhelmed, in many cases. But the worst attack on the state has come from a whole academic and political movement arguing for decentering of the state entirely from its primacy in the provision of security. Scholars of ‘emancipation as security’ argue that the state is itself the very anti-thesis of security and it should be replaced by people organising.

There is a counter-argument led by Mohammed Ayoob, the US based Pakistani Political Scientist to the effect that decentering the state goes against the ‘Third World’ because the state is the only power resource with which ‘Third World’ countries can negotiate their survival in a world order stashed against them. The truth, however, is that the ‘emancipation as security’ movement has gone far. First of all, the United Nations has basically bought that argument. One aspect of that is the nebulous concept of ‘Human Security’ which underpins UNDP politics, for example. The second is the concept of sovereignty that the UN now endorsed. As early as 1990, Kofi Annan went on to declare that the UN Charter was never issued in the name of states or governments but in the name of the people and was about responsible and legitimate power. He meant that if the UN and those who controlled it defined you on the other side of human rights/dignity, you were running a risk that included what clever politicians such as Tony Blair later came to call ‘Humanitarian Intervention’ but which some critic has called ‘Humanitarian Imperialism’. Leaders of ‘Third World’ countries got the message. It was followed closely by the International Criminal Court, (ICC), catching off guard the African leaders who didn’t see it coming. ICC came through global civil society rather than traditional diplomacy. Before they knew it, it was in place. It is only now they are coming to the protest politics about it.

So, a combination of factors and forces has basically hollowed out the state as to, paradoxically, be overwhelmed by anarchy it was created to place. It is difficult to guess how this will play out in a place such as Nigeria where the state is already unravelling, beset by insurgencies, aggravated by intra-elite incoherence and incompetence of the state itself. It is a frightening scenario because it is not evident at all that the state is aware of the complexity of what is unfolding. How the Nigerian State responds would be interesting because it is itself a replica of the African state common to which is the heritage of implantation in popular consciousness mostly through brute force rather than in a hegemonic sense. Its fortune will be a signal to others, especially the question of what happens by the time the new consciousness of decentering the state arrives the continent at popular level.

‘Oil and Instability’

Former president Obasanjo and another two former ones, IBB and Abacha: Are these evidence of ‘oil and instability’ or of something much more complex than that?

Oil has enlisted Nigeria in the club of petro-dollar states. With that, the Nigerian State has enjoyed ample resources with which to reify itself, development wise. But oil comes with its own problems. One of such problems is the attraction that state power acquires as for control of it to become a matter of do or die. The central claim here is that the attraction lies in the fact that (oil) rents are paid to state coffers and is controlled by the state. So, the state becomes too irresistible. Politicians rig elections, kill and do just about any and everything to acquire power. Soldiers also shoot their way to take power. Insurgencies and civil wars become part of it all. All of these, as the argument goes, are so as to sit atop oil money and use it to consolidate, normally by buying loyalty, through direct bribery or developmental concession. In other words, oil goes together with authoritarianism and corruption.

Oil has enlisted Nigeria in the club of petro-dollar states. With that, the Nigerian State has enjoyed ample resources with which to reify itself, development wise. But oil comes with its own problems. One of such problems is the attraction that state power acquires as for control of it to become a matter of do or die. The central claim here is that the attraction lies in the fact that (oil) rents are paid to state coffers and is controlled by the state. So, the state becomes too irresistible. Politicians rig elections, kill and do just about any and everything to acquire power. Soldiers also shoot their way to take power. Insurgencies and civil wars become part of it all. All of these, as the argument goes, are so as to sit atop oil money and use it to consolidate, normally by buying loyalty, through direct bribery or developmental concession. In other words, oil goes together with authoritarianism and corruption.

None of these are strange to Nigeria. It has fought a war that is tightly linked to oil. It is still fighting a war against regular reminder about Nigeria breaking up, understood as an oil informed campaign by interests and forces suspected to habour the secret desire of the possibility of carving out the Niger Delta where Nigeria’s oil wealth is concentrated. The civil war, the campaign, the succession of coups and current strings of insurgencies constitute the evidence for the ‘oil and instability’ thesis powerfully argued initially in radical scholarship in the eighties and recently updated.

Currently, Nigeria battles with resource nationalism politics which oil related environmental devastation in the Niger Delta has provoked or been used to provoke. A strangulating insurgency with a disciplining power on the Nigerian State to the tune of about 7 billion dollars has simply sent a message that challenge the membership of the union of any part of the country that is not an oil production point. Lagos appears to have taken up the challenge while oil search has been intensified in the north. It is all a part of ‘oil and instability’ because it sends the country deeper into the oil trap, into an enclave economy – the very anti-thesis of development for countries such as Nigeria that have the challenge of lifting millions out of poverty immediately. Oil brings a lot of wealth but it is always controlled by less than one per cent of the populace because it has to be financed. That leaves the remaining 90 per cent stranded. There are too few exceptions to sustain a contrary generalization.

So, a country that could beautifully spread economic opportunities on the basis of the cornerstone principles of even and balanced development is lost in such dry debates as restructuring whose consequences could provide further evidence for the ‘oil and instability’ argumentation. A baggage to watch as the management of existing oil and oil related troubles must be informed by a strategic sense of how Nigeria fits into the world in, say, 2050.