My President Was Black, (Part 6)

A history of the first African American White House—and of what came next

For those who have followed the serialization of this piece from the January/February 2017 edition of The Atlantic, this is the last of it. The serialization of this mammoth piece has been argued in the first case in terms of the contextual dimension brought into the telling of the Obama story, the mapping of the various corners of the context and the negotiation of those corners to produce a single, coherent narrative that offers something to almost everyone about the Obama Presidency. In the end, the Obama phenomenon compels everyone to ask if white is necessarily the opposite of black. If, based on the Obama accomplishment, skin color is a matter of difference rather than distinction, then might the answer lie in the writer, Kofi Awoonor‘s thesis that racism thrives because “there is money in racism”?, (African Commentary, August 1990, p. 46).

While we are pondering on that take away, it would be well to contemplate the power of voice Obama embodies today and which, perforce, would have to serve humanity because it is too much of a power resource to serve anything less. At just 56 and with the benefit of the experience of the American presidency, it is the world’s own investment in moral authority. It bears repeating to say this is an elevated and graceful reportage. Its elegance reduces the burden of reading a nearly 17, 000 words. Tomorrow, there will be a ‘postscript’ to this piece by the late Dr Tajudeen Abdulraheem. Don’t miss it – editor:

By Ta-Nehisi Coates

Photograph by Ian Allen

VI “When You Left, You Took All of Me With You”

Mrs Obama with the Miss Obamas

Obama and Hilary Clinton

Obama and successor

A Perspective

One Saturday morning last May, I joined the presidential motorcade as it slipped out of the southern gate of the White House. A mostly white crowd had assembled. As the motorcade drove by, people cheered, held up their smartphones to record the procession, and waved American flags. To be within feet of the president seemed like the thrill of their lives. I was astounded. An old euphoria, which I could not immediately place, gathered up in me. And then I remembered, it was what I felt through much of 2008, as I watched Barack Obama’s star shoot across the political sky. I had never seen so many white people cheer on a black man who was neither an athlete nor an entertainer. And it seemed that they loved him for this, and I thought in those days, which now feel so long ago, that they might then love me, too, and love my wife, and love my child, and love us all in the manner that the God they so fervently cited had commanded. I had been raised amid a people who wanted badly to believe in the possibility of a Barack Obama, even as their very lives argued against that possibility. So they would praise Martin Luther King Jr. in one breath and curse the white man, “the Great Deceiver,” in the next. Then came Obama and the Obama family, and they were black and beautiful in all the ways we aspired to be, and all that love was showered upon them. But as Obama’s motorcade approached its destination—Howard University, where he would give the commencement address—the complexion of the crowd darkened, and I understood that the love was specific, that even if it allowed Barack Obama, even if it allowed the luckiest of us, to defy the boundaries, then the masses of us, in cities like this one, would still enjoy no such feat. These were our fitful, spasmodic years.

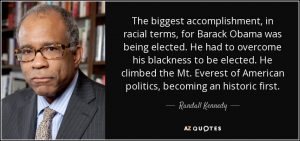

We were launched into the Obama era with no notion of what to expect, if only because a black presidency had seemed such a dubious proposition. There was no preparation, because it would have meant preparing for the impossible. There were few assessments of its potential import, because such assessments were regarded as speculative fiction. In retrospect it all makes sense, and one can see a jagged but real political lineage running through black Chicago. It originates in Oscar Stanton De Priest; continues through Congressman William Dawson, who, under Roosevelt, switched from the Republican to the Democratic Party; crescendos with the legendary Harold Washington; rises still with Jesse Jackson’s 1988 victory in Michigan’s Democratic caucuses; rises again with Carol Moseley Braun’s triumph; and reaches its recent apex with the election of Barack Obama. If the lineage is apparent in hindsight, so are the limits of presidential power. For a century after emancipation, quasi-slavery haunted the South. And more than half a century after Brown v. Board of Education, schools throughout much of this country remain segregated.

There are no clean victories for black people, nor, perhaps, for any people. The presidency of Barack Obama is no different. One can now say that an African American individual can rise to the same level as a white individual, and yet also say that the number of black individuals who actually qualify for that status will be small. One thinks of Serena Williams, whose dominance and stunning achievements can’t, in and of themselves, ensure equal access to tennis facilities for young black girls. The gate is open and yet so very far away.

I felt a mix of pride and amazement walking onto Howard’s campus that day. Howard alumni, of which I am one, are an obnoxious fraternity, known for yelling the school chant across city blocks, sneering at other historically black colleges and universities, and condescending to black graduates of predominantly white institutions. I like to think I am more reserved, but I felt an immense satisfaction in being in the library where I had once found my history, and now found myself with the first black president of the United States. It seemed providential that he would give the commencement address here in his last year. The same pride I felt radiated out across the Yard, the large green patch in the main area of the campus where the ceremony would take place. When Obama walked out, the audience exploded, and when the time came for the color guard to present arms, a chant arose: “O-Ba-Ma! O-Ba-Ma! O-Ba-Ma!”

He gave a good speech that day, paying heed to Howard’s rituals, calling out its famous alumni, shouting out the university’s various dormitories, and urging young people to vote. (His usual riff on respectability politics was missing.) But I think he could have stood before that crowd, smiled, and said “Good luck,” and they would have loved him anyway. He was their champion, and this was evident in the smallest of things. The national anthem was played first, but then came the black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” As the lyrics rang out over the crowd, the students held up the black-power fist—a symbol of defiance before power. And yet here, in the face of a black man in his last year in power, it scanned not as a protest, but as a salute.

Six months later the awful price of a black presidency would be known to those students, even as the country seemed determined not to acknowledge it. In the days after Donald Trump’s victory, there would be an insistence that something as “simple” as racism could not explain it. As if enslavement had nothing to do with global economics, or as if lynchings said nothing about the idea of women as property. As though the past 400 years could be reduced to the irrational resentment of full lips. No. Racism is never simple. And there was nothing simple about what was coming, or about Obama, the man who had unwittingly summoned this future into being. I still want Obama to be right. I still would like to fold myself into the dream. This will not be possible.

It was said that the Americans who’d supported Trump were victims of liberal condescension. The word racist would be dismissed as a profane slur put upon the common man, as opposed to an accurate description of actual men. “We simply don’t yet know how much racism or misogyny motivated Trump voters,” David Brooks would write in The New York Times. “If you were stuck in a jobless town, watching your friends OD on opiates, scrambling every month to pay the electric bill, and then along came a guy who seemed able to fix your problems and hear your voice, maybe you would stomach some ugliness, too.” This strikes me as perfectly logical. Indeed, it could apply just as well to Louis Farrakhan’s appeal to the black poor and working class. But whereas the followers of an Islamophobic white nationalist enjoy the sympathy that must always greet the salt of the earth, the followers of an anti-Semitic black nationalist endure the scorn that must ever greet the children of the enslaved.

Much would be made of blue-collar voters in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Michigan who’d pulled the lever for Obama in 2008 and 2012 and then for Trump in 2016. Surely these voters disproved racism as an explanatory force. It’s still not clear how many individual voters actually flipped. But the underlying presumption—that Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama could be swapped in for each other—exhibited a problem. Clinton was a candidate who’d won one competitive political race in her life, whose political instincts were questioned by her own advisers, who took more than half a million dollars in speaking fees from an investment bank because it was “what they offered,” who proposed to bring back to the White House a former president dogged by allegations of rape and sexual harassment. Obama was a candidate who’d become only the third black senator in the modern era; who’d twice been elected president, each time flipping red and purple states; who’d run one of the most scandal-free administrations in recent memory. Imagine an African American facsimile of Hillary Clinton: She would never be the nominee of a major political party and likely would not be in national politics at all.

Pointing to citizens who voted for both Obama and Trump does not disprove racism; it evinces it. To secure the White House, Obama needed to be a Harvard-trained lawyer with a decade of political experience and an incredible gift for speaking to cross sections of the country; Donald Trump needed only money and white bluster.

In the week after the election, I was a mess. I had not seen my wife in two weeks. I was on deadline for this article. My son was struggling in school. The house was in disarray. I played Marvin Gaye endlessly—“When you left, you took all of me with you.” Friends began to darkly recall the ghosts of post-Reconstruction. The election of Donald Trump confirmed everything I knew of my country and none of what I could accept. The idea that America would follow its first black president with Donald Trump accorded with its history. I was shocked at my own shock. I had wanted Obama to be right.

I still want Obama to be right. I still would like to fold myself into the dream. This will not be possible. By some cosmic coincidence, a week after the election I received a portion of my father’s FBI file. My father had grown up poor in Philadelphia. His father was struck dead on the street. His grandfather was crushed to death in a meatpacking plant. He’d served his country in Vietnam, gotten radicalized there, and joined the Black Panther Party, which brought him to the attention of J. Edgar Hoover. A memo written to the FBI director was “submitted aimed at discrediting WILLIAM PAUL COATES, Acting Captain of the BPP, Baltimore.” The memo proposed that a fake letter be sent to the Panthers’ co-founder Huey P. Newton. The fake letter accused my father of being an informant and concluded, “I want somethin done with this bootlikin facist pig nigger and I want it done now.” The words somethin done need little interpretation. The Panthers were eventually consumed by an internecine war instigated by the FBI, one in which being labeled a police informant was a death sentence.

A few hours after I saw this file, I had my last conversation with the president. I asked him how his optimism was holding up, given Trump’s victory. He confessed to being surprised at the outcome but said that it was tough to “draw a grand theory from it, because there were some very unusual circumstances.” He pointed to both candidates’ high negatives, the media coverage, and a “dispirited” electorate. But he said that his general optimism about the shape of American history remained unchanged. “To be optimistic about the long-term trends of the United States doesn’t mean that everything is going to go in a smooth, direct, straight line,” he said. “It goes forward sometimes, sometimes it goes back, sometimes it goes sideways, sometimes it zigs and zags.”

I thought of Hoover’s FBI, which harassed three generations of black activists, from Marcus Garvey’s black nationalists to Martin Luther King Jr.’s integrationists to Huey Newton’s Black Panthers, including my father. And I thought of the enormous power accrued to the presidency in the post-9/11 era—the power to obtain American citizens’ phone records en masse, to access their emails, to detain them indefinitely. I asked the president whether it was all worth it. Whether this generation of black activists and their allies should be afraid.

“Keep in mind that the capacity of the NSA, or other surveillance tools, are specifically prohibited from being applied to U.S. citizens or U.S. persons without specific evidence of links to terrorist activity or, you know, other foreign-related activity,” he said. “So, you know, I think this whole story line that somehow Big Brother has massively expanded and now that a new president is in place it’s this loaded gun ready to be used on domestic dissent is just not accurate.”

He counseled vigilance, “because the possibility of abuse by government officials always exists. The issue is not going to be that there are new tools available; the issue is making sure that the incoming administration, like my administration, takes the constraints on how we deal with U.S. citizens and persons seriously.” This answer did not fill me with confidence. The next day, President-Elect Trump offered Lieutenant General Michael Flynn the post of national-security adviser and picked Senator Jeff Sessions of Alabama as his nominee for attorney general. Last February, Flynn tweeted “Fear of Muslims is RATIONAL” and linked to a YouTube video that declared followers of Islam want “80 percent of humanity enslaved or exterminated.” Sessions had once been accused of calling a black lawyer “boy,” claiming that a white lawyer who represented black clients was a disgrace to his race, and joking that he thought the Ku Klux Klan “was okay until I found out they smoked pot.” I felt then that I knew what was coming—more Freddie Grays, more Rekia Boyds, more informants and undercover officers sent to infiltrate mosques.

And I also knew that the man who could not countenance such a thing in his America had been responsible for the only time in my life when I felt, as the first lady had once said, proud of my country, and I knew that it was his very lack of countenance, his incredible faith, his improbable trust in his countrymen, that had made that feeling possible. The feeling was that little black boy touching the president’s hair. It was watching Obama on the campaign trail, always expecting the worst and amazed that the worst never happened. It was how I’d felt seeing Barack and Michelle during the inauguration, the car slow-dragging down Pennsylvania Avenue, the crowd cheering, and then the two of them rising up out of the limo, rising up from fear, smiling, waving, defying despair, defying history, defying gravity.