My President Was Black, (Part 4)

A history of the first African American White House—and of what came next

By Ta-Nehisi Coates

Photograph by Ian Allen

4. “You Still Gotta Go Back to the Hood”

Just after Columbus Day, I accompanied the president and his formidable entourage on a visit to North Carolina A&T State University, in Greensboro. Four days earlier, The Washington Post had published an old audio clip that featured Donald Trump lamenting a failed sexual conquest and exhorting the virtues of sexual assault. The next day, Trump claimed that this was “locker room” talk. As we flew to North Carolina, the president was in a state of bemused disbelief. He plopped down in a chair in the staff cabin of Air Force One and said, “I’ve been in a lot of locker rooms. I don’t think I’ve ever heard that one before.” He was casual and relaxed. A feeling of cautious inevitability emanated from his staff, and why not? Every day seemed to bring a new, more shocking revelation or piece of evidence showing Trump to be unfit for the presidency: He had lost nearly $1 billion in a single year. He had likely not paid taxes in 18 years. He was running a “university,” for which he was under formal legal investigation. He had trampled on his own campaign’s messaging by engaging in a Twitter crusade against a former beauty-pageant contestant. He had been denounced by leadership in his own party, and the trickle of prominent Republicans—both in and out of office—who had publicly repudiated him threatened to become a geyser. At this moment, the idea that a campaign so saturated in open bigotry, misogyny, chaos, and possible corruption could win a national election was ludicrous. This was America.

Hurt No one?

The president was going to North Carolina to keynote a campaign rally for Clinton, but first he was scheduled for a conversation about My Brother’s Keeper, his initiative on behalf of disadvantaged youth. Announcing My Brother’s Keeper—or MBK, as it’s come to be called—in 2014, the president had sought to avoid giving the program a partisan valence, noting that it was “not some big new government program.” Instead, it would involve the government in concert with the nonprofit and business sectors to intervene in the lives of young men of color who were “at risk.” MBK serves as a kind of network for those elements of federal, state, and local government that might already have a presence in the lives of these young men. It is a quintessentially Obama program—conservative in scope, with impacts that are measurable.

“It comes right out of his own life,” Broderick Johnson, the Cabinet secretary and an assistant to the president, who heads MBK, told me recently. “I have heard him say, ‘I don’t want us to have a bunch of forums on race.’ He reminds people, ‘Yeah, we can talk about this. But what are we going to do?’ ” On this afternoon in North Carolina, what Obama did was sit with a group of young men who’d turned their lives around in part because of MBK. They told stories of being in the street, of choosing quick money over school, of their homes being shot up, and—through the help of mentoring or job programs brokered by MBK—transitioning into college or a job. Obama listened solemnly and empathetically to each of them. “It doesn’t take that much,” he told them. “It just takes someone laying hands on you and saying, ‘Hey, man, you count.’ ”

When he asked the young men whether they had a message he should take back to policy makers in Washington, D.C., one observed that despite their best individual efforts, they still had to go back to the very same deprived neighborhoods that had been the sources of trouble for them. “It’s your environment,” the young man said. “You can do what you want, but you still gotta go back to the hood.”

He was correct. The ghettos of America are the direct result of decades of public-policy decisions: the redlining of real-estate zoning maps, the expanded authority given to prosecutors, the increased funding given to prisons. And all of this was done on the backs of people still reeling from the 250-year legacy of slavery. The results of this negative investment are clear—African Americans rank at the bottom of nearly every major socioeconomic measure in the country.

Obama’s formula for closing this chasm between black and white America, like that of many progressive politicians today, proceeded from policy designed for all of America. Blacks disproportionately benefit from this effort, since they are disproportionately in need. The Affordable Care Act, which cut the uninsured rate in the black community by at least a third, was Obama’s most prominent example. Its full benefit has yet to be felt by African Americans, because several states in the South have declined to expand Medicaid. But when the president and I were meeting, the ACA’s advocates believed that pressure on state budgets would force expansion, and there was evidence to support this: Louisiana had expanded Medicaid earlier in 2016, and advocates were gearing up for wars to be waged in Georgia and Virginia.

Obama also emphasized the need for a strong Justice Department with a deep commitment to nondiscrimination. When Obama moved into the White House in 2009, the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division “was in shambles,” former Attorney General Eric Holder told me recently. “I mean, I had been there for 12 years as a line guy. I started out in ’76, so I served under Republicans and Democrats. And what the [George W.] Bush administration, what the Bush DOJ did, was unlike anything that had ever happened before in terms of politicized hiring.” The career civil servants below the political appointees, Holder said, were not even invited to the meetings in which the key hiring and policy decisions were made. After Obama’s inauguration, Holder told me, “I remember going to tell all the folks at the Civil Rights Division, ‘The Civil Rights Division is open for business again.’ The president gave me additional funds to hire people.”

The political press developed a narrative that because Obama felt he had to modulate his rhetoric on race, Holder was the administration’s true, and thus blacker, conscience. Holder is certainly blunter, and this worried some of the White House staff. Early in Obama’s first term, Holder gave a speech on race in which he said the United States had been a “nation of cowards” on the subject. But positioning the two men as opposites elides an important fact: Holder was appointed by the president, and went only as far as the president allowed. I asked Holder whether he had toned down his rhetoric after that controversial speech. “Nope,” he said. Reflecting on his relationship with the president, Holder said, “We were also kind of different people, you know? He is the Zen guy. And I’m kind of the hot-blooded West Indian. And I thought we made a good team, but there’s nothing that I ever did or said that I don’t think he would have said, ‘I support him 100 percent.’

“Now, the ‘nation of cowards’ speech, the president might have used a different phrase—maybe, probably. But he and I share a worldview, you know? And when I hear people say, ‘Well, you are blacker than him’ or something like that, I think, What are you all talking about?”

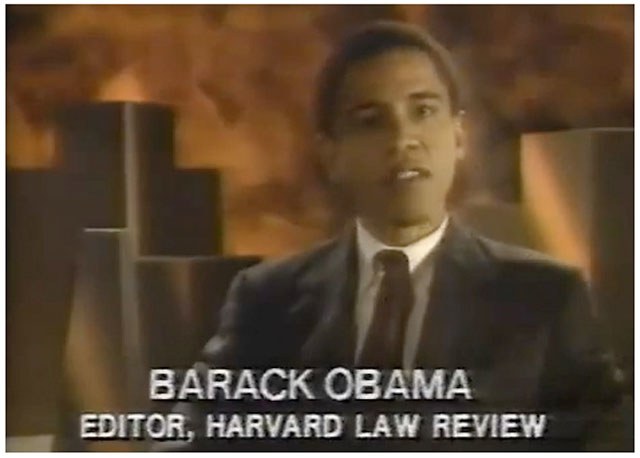

For much of his presidency, a standard portion of Obama’s speeches about race riffed on black people’s need to turn off the television, stop eating junk food, and stop blaming white people for their problems. Obama would deliver this lecture to any black audience, regardless of context. It was bizarre, for instance, to see the president warning young men who’d just graduated from Morehouse College, one of the most storied black colleges in the country, about making “excuses” and blaming whites.

This part of the Obama formula is the most troubling, and least thought-out. This judgment emerges from my own biography. I am the product of black parents who encouraged me to read, of black teachers who felt my work ethic did not match my potential, of black college professors who taught me intellectual rigor. And they did this in a world that every day insulted their humanity. It was not so much that the black layabouts and deadbeats Obama invoked in his speeches were unrecognizable. I had seen those people too. But I’d also seen the same among white people. If black men were overrepresented among drug dealers and absentee dads of the world, it was directly related to their being underrepresented among the Bernie Madoffs and Kenneth Lays of the world. Power was what mattered, and what characterized the differences between black and white America was not a difference in work ethic, but a system engineered to place one on top of the other.

The mark of that system is visible at every level of American society, regardless of the quality of one’s choices. For instance, the unemployment rate among black college graduates (4.1 percent) is almost the same as the unemployment rate among white high-school graduates (4.6 percent). But that college degree is generally purchased at a higher price by blacks than by whites. According to research by the Brookings Institution, African Americans tend to carry more student debt four years after graduation ($53,000 versus $28,000) and suffer from a higher default rate on their loans (7.6 percent versus 2.4 percent) than white Americans. This is both the result and the perpetuator of a sprawling wealth gap between the races. White households, on average, hold seven times as much wealth as black households—a difference so large as to make comparing the “black middle class” and “white middle class” meaningless; they’re simply not comparable. According to Patrick Sharkey, a sociologist at New York University who studies economic mobility, black families making $100,000 a year or more live in more-disadvantaged neighborhoods than white families making less than $30,000. This gap didn’t just appear by magic; it’s the result of the government’s effort over many decades to create a pigmentocracy—one that will continue without explicit intervention.

Obama had been on the record as opposing reparations. But now, late in his presidency, he seemed more open to the idea—in theory, at least, if not in practice. “Theoretically, you can make obviously a powerful argument that centuries of slavery, Jim Crow, discrimination are the primary cause for all those gaps,” Obama said, referencing the gulf in education, wealth, and employment that separates black and white America. “That those were wrongs to the black community as a whole, and black families specifically, and that in order to close that gap, a society has a moral obligation to make a large, aggressive investment, even if it’s not in the form of individual reparations checks but in the form of a Marshall Plan.”

The political problems with turning the argument for reparations into reality are manifold, Obama said. “If you look at countries like South Africa, where you had a black majority, there have been efforts to tax and help that black majority, but it hasn’t come in the form of a formal reparations program. You have countries like India that have tried to help untouchables, with essentially affirmative-action programs, but it hasn’t fundamentally changed the structure of their societies. So the bottom line is that it’s hard to find a model in which you can practically administer and sustain political support for those kinds of efforts.”

Obama went on to say that it would be better, and more realistic, to get the country to rally behind a robust liberal agenda and build on the enormous progress that’s been made toward getting white Americans to accept nondiscrimination as a basic operating premise. But the progress toward nondiscrimination did not appear overnight. It was achieved by people willing to make an unpopular argument and live on the frontier of public opinion. I asked him whether it wasn’t—despite the practical obstacles—worth arguing that the state has a collective responsibility not only for its achievements but for its sins.

“I want my children—I want Malia and Sasha—to understand that they’ve got responsibilities beyond just what they themselves have done,” Obama said. “That they have a responsibility to the larger community and the larger nation, that they should be sensitive to and extra thoughtful about the plight of people who have been oppressed in the past, are oppressed currently. So that’s a wisdom that I want to transmit to my kids … But I would say that’s a high level of enlightenment that you’re looking to have from a majority of the society. And it may be something that future generations are more open to, but I am pretty confident that for the foreseeable future, using the argument of nondiscrimination, and ‘Let’s get it right for the kids who are here right now,’ and giving them the best chance possible, is going to be a more persuasive argument.”

Obama is unfailingly optimistic about the empathy and capabilities of the American people. His job necessitates this: “At some level what the people want to feel is that the person leading them sees the best in them,” he told me. But I found it interesting that that optimism does not extend to the possibility of the public’s accepting wisdoms—such as the moral logic of reparations—that the president, by his own account, has accepted for himself and is willing to teach his children. Obama says he always tells his staff that “better is good.” The notion that a president would attempt to achieve change within the boundaries of the accepted consensus is appropriate. But Obama is almost constitutionally skeptical of those who seek to achieve change outside that consensus.

Early in 2016, Obama invited a group of African American leaders to meet with him at the White House. When some of the activists affiliated with Black Lives Matter refused to attend, Obama began calling them out in speeches. “You can’t refuse to meet because that might compromise the purity of your position,” he said. “The value of social movements and activism is to get you at the table, get you in the room, and then start trying to figure out how is this problem going to be solved. You then have a responsibility to prepare an agenda that is achievable—that can institutionalize the changes you seek—and to engage the other side.”

Opal Tometi, a Nigerian American community activist who is one of the three founders of Black Lives Matter, explained to me that the group has a more diffuse structure than most civil-rights organizations. One reason for this is to avoid the cult of personality that has plagued black organizations in the past. So the founders asked its membership in Chicago, the president’s hometown, whether they should meet with Obama. “They felt—and I think many of our members felt—there wouldn’t be the depth of discussion that they wanted to have,” Tometi told me. “And if there wasn’t that space to have a real heart-to-heart, and if it was just surface level, that it would be more of a disservice to the movement.”

Tometi noted that some other activists allied with Black Lives Matter had been planning to attend the meeting, so they felt their views would be represented. Nevertheless, Black Lives Matter sees itself as engaged in a protest against the treatment of black people by the American state, and so Tometi and much of the group’s leadership, concerned about being used for a photo op by the very body they were protesting, opted not to go.

When I asked Obama about this perspective , he fluctuated between understanding where the activists were coming from and being hurt by such brush-offs. “I think that where I’ve gotten frustrated during the course of my presidency has never been because I was getting pushed too hard by activists to see the justness of a cause or the essence of an issue,” he said. “I think where I got frustrated at times was the belief that the president can do anything if he just decides he wants to do it. And that sort of lack of awareness on the part of an activist about the constraints of our political system and the constraints on this office, I think, sometimes would leave me to mutter under my breath. Very rarely did I lose it publicly. Usually I’d just smile.”

He laughed, then continued, “The reason I say that is because those are the times where sometimes you feel actually a little bit hurt. Because you feel like saying to these folks, ‘[Don’t] you think if I could do it, I [would] have just done it? Do you think that the only problem is that I don’t care enough about the plight of poor people, or gay people?’ ”

I asked Obama whether he thought that perhaps protesters’ distrust of the powers that be could ultimately be healthy. “Yes,” he said. “Which is why I don’t get too hurt. I mean, I think there is a benefit to wanting to hold power’s feet to the fire until you actually see the goods. I get that. And I think it is important. And frankly, sometimes it’s useful for activists just to be out there to keep you mindful and not get complacent, even if ultimately you think some of their criticism is misguided.”

Obama himself was an activist and a community organizer, albeit for only two years—but he is not, by temperament, a protester. He is a consensus-builder; consensus, he believes, ultimately drives what gets done. He understands the emotional power of protest, the need to vent before authority—but that kind of approach does not come naturally to him. Regarding reparations, he said, “Sometimes I wonder how much of these debates have to do with the desire, the legitimate desire, for that history to be recognized. Because there is a psychic power to the recognition that is not satisfied with a universal program; it’s not satisfied by the Affordable Care Act, or an expansion of Pell Grants, or an expansion of the earned-income tax credit.” These kinds of programs, effective and disproportionately beneficial to black people though they may be, don’t “speak to the hurt, and the sense of injustice, and the self-doubt that arises out of the fact that [African Americans] are behind now, and it makes us sometimes feel as if there must be something wrong with us—unless you’re able to see the history and say, ‘It’s amazing we got this far given what we went through.’

“So in part, I think the argument sometimes that I’ve had with folks who are much more interested in sort of race-specific programs is less an argument about what is practically achievable and sometimes maybe more an argument of ‘We want society to see what’s happened and internalize it and answer it in demonstrable ways.’ And those impulses I very much understand—but my hope would be that as we’re moving through the world right now, we’re able to get that psychological or emotional peace by seeing very concretely our kids doing better and being more hopeful and having greater opportunities.”

Obama saw—at least at that moment, before the election of Donald Trump—a straight path to that world. “Just play this out as a thought experiment,” he said. “Imagine if you had genuine, high-quality early-childhood education for every child, and suddenly every black child in America—but also every poor white child or Latino [child], but just stick with every black child in America—is getting a really good education. And they’re graduating from high school at the same rates that whites are, and they are going to college at the same rates that whites are, and they are able to afford college at the same rates because the government has universal programs that say that you’re not going to be barred from school just because of how much money your parents have.

“So now they’re all graduating. And let’s also say that the Justice Department and the courts are making sure, as I’ve said in a speech before, that when Jamal sends his résumé in, he’s getting treated the same as when Johnny sends his résumé in. Now, are we going to have suddenly the same number of CEOs, billionaires, etc., as the white community? In 10 years? Probably not, maybe not even in 20 years.

“But I guarantee you that we would be thriving, we would be succeeding. We wouldn’t have huge numbers of young African American men in jail. We’d have more family formation as college-graduated girls are meeting boys who are their peers, which then in turn means the next generation of kids are growing up that much better. And suddenly you’ve got a whole generation that’s in a position to start using the incredible creativity that we see in music, and sports, and frankly even on the streets, channeled into starting all kinds of businesses. I feel pretty good about our odds in that situation.”

The thought experiment doesn’t hold up. The programs Obama favored would advance white America too—and without a specific commitment to equality, there is no guarantee that the programs would eschew discrimination. Obama’s solution relies on a goodwill that his own personal history tells him exists in the larger country. My own history tells me something different. The large numbers of black men in jail, for instance, are not just the result of poor policy, but of not seeing those men as human.

When President Obama and I had this conversation, the target he was aiming to reach seemed to me to be many generations away, and now—as President-Elect Trump prepares for office—seems even many more generations off. Obama’s accomplishments were real: a $1 billion settlement on behalf of black farmers, a Justice Department that exposed Ferguson’s municipal plunder, the increased availability of Pell Grants (and their availability to some prisoners), and the slashing of the crack/cocaine disparity in sentencing guidelines, to name just a few. Obama was also the first sitting president to visit a federal prison. There was a feeling that he’d erected a foundation upon which further progressive policy could be built. It’s tempting to say that foundation is now endangered. The truth is, it was never safe.