This piece which speaks to what can be considered the most important or central issues about Africa in the emerging world order has been reproduced from Daily Maverick, (December 11th, 2016) which introduced Ronak Gopaldas, the author, as a political economist with an eye on the emerging markets – Editor

Amid the present geopolitical shake-up, an opportunity exists for Africa to exploit a vacuum created by increasingly fragile Europe, an inward looking and protectionist US and a rebalancing and domestically focused China.

In the aftermath of the US Presidential election, a speculative storm has ensued around the type of polices President-elect Donald Trump will pursue. The lingering uncertainty has created major headaches for policy-makers across the globe as they attempt to navigate an ambiguous new world order. For the African continent, in particular, the prospects regarding economic, trade and foreign policy look dim. While it seems likely the continent will need to brace itself for more difficult times, it is worth asking whether there are in fact potential opportunities emerging from the doom and gloom.

At face value, the answer is no. A Trump presidency represents another victory for anti-globalisation and is likely to lead to more insular and protectionist policies. Such protectionism has the possibility to trigger trade wars, complicating the picture for an already weak global economy. The result would be negative for emerging market currencies and could lead to competitive devaluations and retaliatory measures from affected countries.

With Africa unlikely to feature highly on Trump’s priority list, the three primary channels of real economic activity – trade, developmental assistance, and foreign investment – could also come under significant pressure. Furthermore, remittances, which represent a huge source of dollar inflows to the continent, may see sharp declines. A combination of these factors could spell trouble for African economies already buckling under the strain of lower commodity prices.

While the prospects of greater fiscal stimulus under a Trump presidency could ignite stronger US economic growth, such actions may have unintended consequences. For example, if it forces the Fed to raise interest rates at a faster rate, global bond markets will suffer, probably leading to investors short-circuiting flows to emerging and African markets. In any event, a stronger dollar seems likely, which does not bode well for African currencies, African countries’ debt servicing obligations, or commodity prices. With resource demand already hard-hit by the Chinese slowdown and further uncertainties still to come from Brexit, this will be another hefty blow to the continent’s growth prospects.

With very little help forthcoming from the external environment, Africa needs to decide whether it will simply accept its fate as a victim to such global events or whether it will attempt to chart a course where the continent emerges in a favourable manner. Policy-makers on the continent will need to adapt to the new environment with more creative and innovative strategies to manage their economic problems.

Amid this geopolitical shake-up, an opportunity exists for the continent to now exploit a vacuum created by increasingly fragile Europe, an inward looking and protectionist US and a rebalancing and domestically focused China. With crafty and ambitious leadership, it may in fact be possible for the African continent to meaningfully exert its influence on a global stage. However, to achieve this will require some deft and decisive leadership, strategic thinking and the prioritisation of three key areas, in particular, to be successful.

First, Africa’s leadership needs to recognise that relevance will only be achieved as a collective. Fragmentation, and the inability to speak with one clear voice on global issues, has been a major drawback in the past and has muted the continent’s influence in global debates and fora. While each country on the continent has its own distinct features and complexities, it is only by standing together that Africa can exploit its considerable advantages relative to other regions of the world. When viewed on a continental level, features such as its population and market size, favourable demographics, rapidly urbanising and rising middle class, and technological advances, become too big to ignore. Using the power of the collective adds both scale and gravitas to Africa’s global voice and will allow the continent to adopt a more muscular approach to international affairs.

However, a stronger and more decisive African Union (AU) is central to this idea. In its current form, the AU has often been behind the curve or at odds with its members on issues of continental importance, most notably in the response to the crises in Libya and Cote D’Ivoire. To galvanise Africa around issues of common interest would also require Africa’s largest economies, Nigeria, South Africa and Egypt – all currently struggling economically and preoccupied with domestic issues – to take the lead in driving the strategic agenda and building consensus.

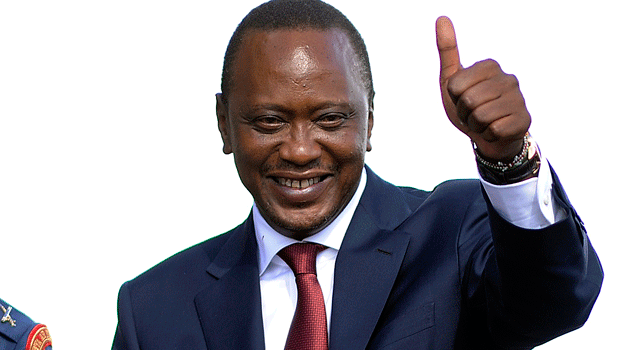

Second, a more tactical approach is required to exploit the potential opportunities for the continent amid global volatility. Kenya is one county that seems to have mastered this approach and which has understood the intricacies of the relationship between economic growth, economic diplomacy and conventional diplomacy.

Indeed, the “economic diplomacy” adopted by Kenya since 2013 offers a blueprint for other continental leaders. Rather than adopting ideological foreign policy stances, the country has pursued a pragmatic approach to diplomacy aimed at priming the country in ways that have attracted significant foreign direct investment, tourism dollars and international conferencing.

The success of this approach can be largely attributed to Foreign Secretary Dr Amina Mohamed. As chairman of the Media Owner Association, Hanningtone Gaya argues in a column for Kenya’s The Star newspaper: “In less than four years, she has revamped Kenya’s global image, from a position bedevilled by sanctions threats, to a preferred destination for global trade and investment and conferencing, coupled with a massive infusion of foreign direct investments. The strong investor confidence in the country is a function of the assertive and proactive economic diplomacy that Mohamed has championed.” With Dr Mohamed now in line to lead the AU, her candidature bodes well if she is able to replicate domestic success on a continental level.

Third, as much of the world looks inward, this ironically may be exactly what Africa needs to address some of its most pressing economic issues. Indeed, Africa is in a unique position in that it has the chance to trade with an untapped market – itself. However, as Africa Renewal’s editor-in-chief Masimba Tafirenyika notes in a 2014 article for the magazine: “Trade only flourishes when countries produce what their trading partners are eager to buy. With a few exceptions, this is not yet the case with Africa. It produces what it doesn’t consume and consumes what it doesn’t produce. It’s a weakness that often frustrates policy-makers; it complicates regional integration and is a primary reason for the low intra-regional trade, which is between 10% and 12% of Africa’s total trade.”

It’s is no surprise that the level of intra-Africa trade is so poor with over 80% of Africa’s exports shipped overseas. With complex and cumbersome trade rules, cross-border restrictions and poor transport and infrastructure networks thrown in the mix, stimulating intra-Africa trade remains a daunting challenge.

However, in light of external headwinds and the poor performance of the continent’s trading partners, there may now be no other alternative but to kick-start intra-regional trade. Greater integration would enable the continent to develop larger regional markets and build capacity to initiate African solutions to Africa’s economic and political problems. But for this to happen, it will take much more than political rhetoric. It will require practical steps and political will to move from policy to action.

With populism and nationalism sweeping the globe, African countries now need to position themselves to either ride the wave or be engulfed by it. However, to be successful will require a massive departure from the status quo and the prioritisation of the three above-mentioned areas. The combination of these options may yet be Africa’s winning strategy in an increasingly integrated yet marginalising global economy.