Good old Africa

Trump, once credited with a recolonisation of Africa for another 100 years

A Kenyan newspaper’s representation of it all

By Adagbo Onoja

Punditry is already getting it wrong, going hysterical about how Donald doesn’t have one idea about Africa, how empty of Africa his own map of the world is. Others are afraid that under Trump, aid would dry off completely for Africa. Everyone is trying to answer the question whether the man who assumes power shortly as the president of the United States of Africa understands Africa. So far, they are using categories which have timed out such as what would be US aid policy towards Africa or her politics of access to Africa’ resource over-abundance. US-Africa relations no longer follow those categories. There is a whole new logic of US involvement in Africa which does not allow any American president the luxury of being ignorance about Africa anymore. But the journey to this point has been distressing for the poorest continent in the world.

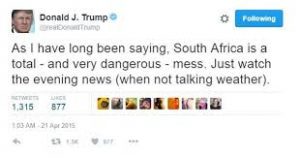

Another Trump speak

Impressions of Trump-talk

Implied in the importance attached to an American president’s awareness of Africa is the notion that it would help if the president of the most powerful country in the world has detailed knowledge of the continent. The assumption is that since meaning is specific, such would dispose the president to being more sensitive or considerate in dealing with the crisis ridden continent. Analysts would say that the assumption or concern itself is warranted by History. After all, it was only in the post 9/11 era that Africa began to matter as Africa to the US. Before then, the continent mattered to the great power in relation to one specific national interest of the US or the other rather than the security or interests of the continent itself. Either Europe or the IMF was tasked with managing Africa for the US before then. It was such that in the year 2000, George W. Bush, a presidential contender stated frankly that his country had no strategic interests in Africa. Five full years before Bush, the Pentagon operated on documents that would say that freed by the collapse of the USSR to pursue strategic interests in Africa beyond Cold War concerns, the US found no such strategic interests to pursue in Africa. In other words, US involvement in Africa in the post independence years rarely went beyond access to human and material resources, particularly liquid and solid minerals. As more sensitive players such as Clinton once pointed out very aptly, the US was more concerned with how Africa countries voted at the United Nations than whether African countries provided their citizens the right to vote. It was that bad.

Then 9/11 changed that logic of US foreign policy. In 2007, the Americans took a remarkable step. That was the announcement of AFRICOM on the same day that Hu Jintao, the then Chinese President was rounding off an African tour, the message of which the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not miss if its statement on that is anything to go by. In the statement, it said that Americans saw military diplomacy as a way to counterbalance China and to maintain a strategic edge. With AFRICOM, the continent began to emerge into what has been called the hub of the ‘Global War on Terror’, (GWOT), the GWOT itself becoming the main menu in US-African relations over and above every other items, according to some analysts. This is in the sense that whichever element of the relationship is in focus, it had something to do with the GWOT or with AFRICOM, be it the substantial US commitment to Drone Warfare in Africa, securing Somalia, relationship with African militaries or the 2010 regime change in Libya. Only the US-Africa Leaders Summit held in 2014 had any element of inter-subjective interaction although critics say it was a great power monologue, properly speaking. But even then, the summit was overshadowed by China. American academics, media and think tanks all said it was a strategy to catch up with China in Africa. Even the name US-Africa Leaders Summit was a near replica of China’s framework for her relationship with Africa: Forum for China-Africa Cooperation, (FOCAC). And China was the only other country constantly a subject of formal securitization throughout the Summit.

In other words, those like the editor of an energy newspaper who proclaimed in 2013 that the US never had a bogeyman like China since the Cold War and that the bogeyman is lurking in Africa were acting out that belief. US’s perception of Africa had shifted from neglect to engagement but not because of oil as popularly believed. Rather, it is because of China, its peer competitor. There was the evidence in Bush who could see no strategic interests of America in Africa in 2000 but could now see so much of such interests seven years later after oil as reason for GWOT had suffered theoretical disgrace. In 2014, at the US-Africa Leaders Summit, China was presented as the contrast of Africa’s “good partner, an equal partner and a partner for the long term”. That was Obama speaking. He was followed by others, some of them saying China “spent lavishly on the continent mainly to lock up mineral resources for its booming economy”.

It seemed the summit had been called to actually catch up with China in Africa even as the reason why the gap implied between the US and China in Africa came about were never pointed out officially. It was US researchers and think tanks that were more forthcoming on that, showing how China accounted for 53% of the tremendous growth in Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) on the continent between 2000 and 2012. Some accounts put this growth in FDI to $27.2billion in 2001 to about $133billion in 2012. And China was not followed by the US but by Japan and her 29%. The US was still not the third. Instead, that was occupied by the EU with its 16%, followed by the 14% recorded for the US. The message is that the US practically divested from Africa in the post Cold War years, practically leaving the space to China as the key player.

Correcting this took the form of a return of the US to Africa with vengeance, in theory and in practice. While the Chinese image, warts and all, was in the construction works to her credit across Africa, America’s image was in the bombing campaigns or the so-called anti-terror operations that occupied its diplomacy across the continent. The continent that had no US drone wars up to the year 2007 suddenly brimmed with about 12 air bases, including Camp Lemonier in Djibouti, the only one that is permanent out of the lot spread across Niger, Ethiopia, Seychelles, Mauritania, Ouagadougou, Uganda, DRC and South Sudan, according to January 2013 figures. General Carter Ham, who commanded AFRICOM put the wisdom in this muscular diplomacy to the imperative to secure “America, Americans and American interests by fighting them over there so that we don’t fight them over here”. That is a plain way of saying that there is nothing wrong if Africa remains the battleground once America is safe.

Meanwhile, the grand canvass as it kept coming from official documents, some of them leaked to US newspapers such as the 1992 Defense Planning Guidance is the rhetoric of disallowing the emergence of a peer competitor. In the aftermath of the collapse of the USSR, everyone knows who the peer competitor in question is: China. Obama’s first term Secretary of State, Hilary Clinton who just crashed out disastrously in a presidential contest framed China in Africa in terms of ‘New Colonialism’. She was the architect of the securitization of China in Africa, itemizing human rights, the environment, democracy, good governance and labour standards as the areas threatened by China. But in the Rand Corporation publication, African leaders, to the last man, including well known ‘allies’ of the US, pronounced China as the great friend of the continent. In all cases, US image in Africa has been tottering in an unmitigated way. Tottering in the sense that people link all US exertions on the continent to an agenda of global primacy codified in the rhetoric of disallowing the emergence of a peer competitor. And the question is, why turn a poverty stricken continent such as Africa into the 21st century geopolitical battleground?

What would Trump do? The morning suggests the character of a day, we are told. James Woolsey, a Trump security adviser is speaking the language of global primacy already. ‘Under Donald Trump, the US will accept China’s rise – as long as it doesn’t challenge the status quo’ is the headline of a South China Morning Post headline Woolsey published on November 10th, 2016. It began by saying that the United States remains the leading military force in the world and the “only country that can project power in volumes sufficient to deter enemies, decide wars and pacify entire regions”. The writer justifies US interventions, saying they were never self-serving missions but responses to such challenges as inhumane oppression, stark violations of international law or in response to humanitarian catastrophes. And even went on to claim that “Our so-called interventionism in the wars against Imperial Japan, Nazi Germany or Baathist Iraq is the reason why countries like Kuwait, Australia, France, Poland and even China are sovereign countries today”. The rhetoric speaks for itself. He was speaking in relation to the bargaining of power in Asia but that essay will nearly stand if you remove Asia and implant Africa.

So, ‘China in Africa’ will compel Trump to know Africa. That is not open to debate but it would be in the context of the struggle for global primacy, not because Africa has acquired any strategic importance in American politics. The question is what Africa might be thinking in terms of how to bargain its way out of being the battleground for great powers competition. Might African leaders, media, academics and civil society players be thinking of a way out in getting both powers to buy into a joint development plan for the continent? That is a development plan that privileges rapid industrial transformation. As the Chinese say, the key issue is not the color of the cat but whether it can catch mouse. A distinctly great power supervised development plan for Africa leaves something for Africa development wise, it involves the two powers in something more beneficial for everyone rather than the selfishness of the satiated and it makes a global peacemaker of Africa, the continent that has been mistreated, historically. Otherwise, the current phase of great power competition in Africa has risks of replicating its 19th and 20th century versions.