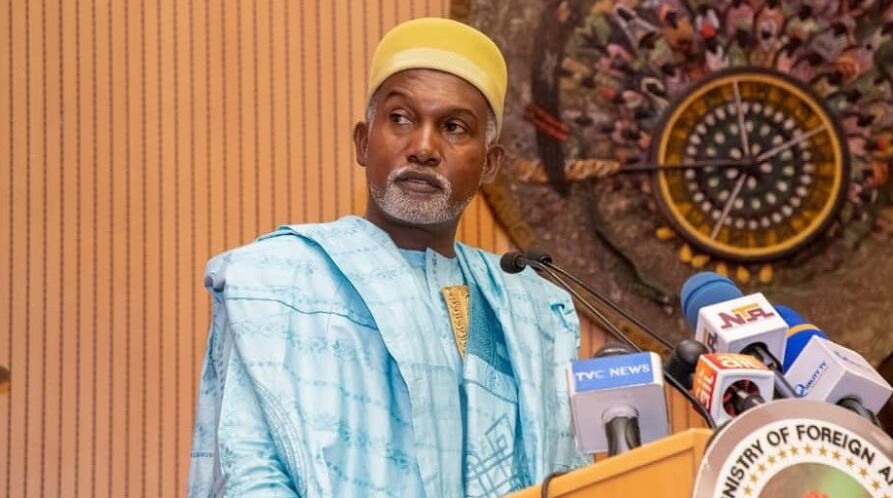

By Ambassador Usman Sarki

“We are watching the strangulation of 2 million people, 61,000 of them have already died. It’s disgraceful and disgusting. History will judge, history will judge those who stood by and did nothing when they could have done something”, The Right Honourable Jeremy Corbin, MP

Since those prophetic words were uttered by the Honourable Jeremy Corbin, MP, the death toll in Gaza and other Occupied Palestine Territories have risen sharply. The destruction of Gaza and its effacement from the map is now almost complete. The displacement of the remnants of its more than 2 million suffering population that have not been killed off has entered a genocidal phase. The muted response of the world to these atrocities is unprecedented and terrifying. The paralysis of the regional powers and other countries is also demoralising and an effective capitulation to the overwhelming power of Israel and its allies over their fates and safety. For those bent on embracing the State of Israel and maintaining close relationship with that entity, it is recommended that they read Ernst Fraenkel’s book, “The Dual State: A Contribution to the Theory of Dictatorship”. They should be made aware of Fraenkel’s classification of states into the “Normative State” that respects law and order and abides by its obligations and commitments, and the “Prerogative State” that solely relies on arbitrary power and violence and the destruction of norms, ethics and rules uninhibited by legal guarantees. This is the reality of dealing with Israel today.

For more than half a century, Nigeria has prided itself on being a voice of reason, moderation, and justice in global affairs. From the earliest days of independence, successive governments in Lagos and later in Abuja championed Africa’s solidarity with oppressed peoples and consistently articulated the principles of self-determination, justice, and peaceful coexistence. Nigeria also stood for racial rights and equality and against racial injustices and discriminations. One of the most visible arenas where these values were put into practice was in Nigeria’s approach to the Israel-Palestinian conflict. In recent years, however, there is growing evidence that Nigeria has quietly retreated from that once constructive role, content instead to take perfunctory positions, abstain when it matters most, or hedge its bets in ways that suggest the weakening of its diplomatic will.

This retreat raises some fundamental questions not only about Nigeria’s standing in international diplomacy, but also about the very coherence of its foreign policy. In the 1970s and 1980s, Nigeria earned respect for its principled stance on the Middle East crisis. The country was unequivocal in its support for Palestinian rights, aligning with the broader African and Non-Aligned Movement consensus. Nigeria condemned Israeli occupation, voted consistently in favour of Palestinian resolutions at the United Nations, and opened its doors to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). The October 1973 Arab-Israeli War was a turning point. Nigeria not only severed diplomatic ties with Israel in solidarity with Egypt and Syria. At the United Nations, Nigeria’s record spoke clearly of its determination. From the 1970s, Nigerian diplomats aligned themselves with resolutions affirming the Palestinians’ right to self-determination, sovereignty, and independence. The vote in 2012 to recognize Palestine as a non-member observer state confirmed this pattern of consistency. In those moments, Nigeria’s voice was not just a matter of routine voting but it was a declaration that Africa’s liberation ethos extended beyond the continent to embrace Palestine as part of a global struggle against racism, occupation and dispossession.

This commitment was mirrored on the African stage as well. Within the Organization of African Unity (OAU), Nigeria was among the champions of Palestinian rights, backing resolutions in the mid-1970s that aligned with the United Nations’ 1974 upgrade of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and consistently condemning occupation while affirming the principle of self-determination. When the African Union (AU) replaced the OAU in 2002, Nigeria carried forward this tradition. The State of Palestine today holds an observer status at the AU thanks to Nigeria, and a large majority of AU member-states recognise it bilaterally. Nigeria has used AU platforms, including the AU Peace and Security Council, to reiterate its support for a two-state solution anchored in international law with East Jerusalem as the capital of the State of Palestine established around the 1967 borders.

A file photo . Courtesy: The New Statesman

These positions were not only seen in resolutions and speeches. They were also embodied in symbolic gestures. The late President Yasser Arafat’s visit to Abuja on June 7, 1998 underlined the political and moral affinity Nigeria projected towards Palestine. His presence drew a direct line between Palestinian liberation and Africa’s fight against colonialism, and underscored Nigeria’s role as a continental leader and moral voice in the Non-Aligned Movement. Within Africa, Nigeria’s stand influenced others, reinforcing the continent’s collective bargaining power and cementing its image as a champion of justice in global forums. Nigeria’s solidarity with Palestine was not merely rhetorical and symbolic; it was demonstrated through visible, high-level diplomacy. Yasser Arafat’s visits on several occasions and his reception with the full honours reserved for visiting heads of state were emblematic of the support by Nigeria to the Palestinian cause.

These visits symbolised Nigeria’s recognition of the Palestinian struggle as parallel to Africa’s own anti-colonial experience and gave practical expression to the country’s support for self-determination. They also underscored the moral stature Nigeria enjoyed across the Global South as a trusted friend of liberation movements. The image of Arafat in Abuja, embraced by Nigerian leaders and celebrated by the public, reflected not only solidarity with Palestine but also Nigeria’s willingness to project justice and self-determination as cornerstones of its foreign relations. Nigeria once again demonstrated its activist diplomacy three decades later when, in 2009, it played an instrumental role in the establishment of the United Nations Human Rights Council’s fact-finding mission on Gaza, which became known as the Goldstone Commission. At that time, the Council was chaired by Nigeria’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations in Geneva, His Excellency Dr. Martin I. Uhomoubhi. This landmark initiative was significant because it directly addressed violations of international law during the Gaza conflict and insisted that accountability was essential to peace. By spearheading such a process, Nigeria showed that it could marry procedural leadership with substantive commitment to universal principles of justice and human rights and dignity.

The Commission reflected positively on Nigeria’s image worldwide and buttressed its claim to moral authority in matters of international justice. Despite the tremendous pressure that was brought to bear on Nigeria, Ambassador Uhomoibhi showed grit and determination and went on to establish the Commission. Today, its findings have become part of the corpus of international human rights and humanitarian law that cannot be effaced from the statutes on civilized norms and practices. Nigeria’s voice was also amplified and proclaimed loudly in the world by very senior personalities like His Excellency Ambassador Joseph Ubaka Ayalogu, Permanent Representative in Geneva, and Her Excellency Professor U. Joy Ogwu, Permanent Representative in New York. They articulated Nigeria’s positions and led African opinion with courage, foresight, indomitable spirit and the willingness to weather the storm of criticism and adversity from Israel’s supporters.

Nigeria did not pursue a one-sided policy in favor of Palestine and against Israel. On the contrary, it strove to maintain a balanced attitude without compromising its attachment to the principles of self-determination of peoples and decolonisation. Nigeria restored relations with Israel in 1992 and successively maintained its position on a two-states solution by accepting the right of Israel to exist. It also collaborated with Israel on many fronts in the domestic arena in Nigeria. Since 2010 or thereabout, successive Nigerian administrations have oscillated between cautious pragmatism and quiet disengagement. On paper, Nigeria still subscribed to the two-state solution and reiterated support for Palestinian self-determination. In practice, however, it often chose silence over vocal reiteration in moments of crisis. While South Africa, Algeria, and other African states continued to speak with moral clarity, Nigeria appeared more hesitant, constrained by new diplomatic alignments, economic interests, and perhaps a diminished sense of its own global mission.

This ambivalence has been glaring in Nigeria’s symbolic but clearly demonstrative gestures that have been playing out of recent. Receiving the Israeli Ambassador in the Aso Rock Villa and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs while that country conducts the most heinous crimes against humanity in Gaza and other Occupied Palestinian Territories, makes Nigeria’s profession of even-handedness appear opportunistic and mercenary in nature. Nigeria must at this crucial moment speak loudly and unambiguously about Israeli crimes not only against Palestinians but against the entire humanity, given the flagrant violations of human rights and the complete contempt shown towards international law. Silence or diplomatic pleasantries in such circumstances risk compromising Nigeria’s historic moral compass and cheapening its international credibility.

The impression of retreat is further reinforced by Nigeria’s recent embrace of bilateral overtures from Israel. In August 2025, Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Ambassador Bianca Odumegwu-Ojukwu, formally received Israel’s Deputy Foreign Minister, Sharren Miriam Haskel-Harpaz, in Abuja. She also received the Ambassador of Israel in her office. The official line was that the meetings focused on “strengthening relations between both countries,” deepening cooperation in security, counter-terrorism, economic development, technology, and innovation. Earlier this year, discussions were also held about establishing a joint commission to institutionalise collaboration in agriculture, food security, trade, and technology exchange. These steps are framed as “pragmatic”, but the optics tell another story. At the very moment when Israel is facing international condemnation and isolation for its war in Gaza and its policies in the Occupied Territories, Nigeria is choosing to advertise “enduring and strategic partnership” with it.

These engagements must also be seen in a wider and troubling context. Israel today is not simply a small Middle Eastern state seeking partnerships abroad. It is a state engaged in conflicts in several fronts with many countries. It is s state that is deeply implicated in the destabilisation of regions far beyond its borders. Its record in arming regimes and non-state actors, selling surveillance technology to authoritarian governments, and exporting counter-insurgency doctrines has been widely criticised for fueling conflicts rather than resolving them. In Africa, Israeli security firms and intelligence contractors have operated in ways that exploit fragile states, often deepening mistrust between communities. Nigeria has not been immune. For decades, religious and ethnic divisions have been manipulated by external actors, and Israel has played a role sometimes subtle and sometimes overt, in reinforcing these fissures.

President Tinubu on the world stage

Security training and arms sales may be seen as necessary deals that would strengthen Nigeria’s internal security, but maintaining selective partnerships across Nigeria’s internal divides along regional, religious and ethnic lines, have far-reaching implications on the country’s unity, independence and sovereignty. They go beyond normal relationships and foster an atmosphere of deep suspicion. Instead of acting as a bridge-builder or peacemaker, Israel’s presence in Nigeria has often translated into an extension of its global playbook: leveraging divisions for influence and embedding itself in domestic fault lines thereby aggravating rather than alleviating tensions. Seen in this light, the sight of Nigerian ministers welcoming Israeli diplomats at the height of atrocities in Gaza cannot be dismissed as routine diplomacy. It represents a tacit endorsement of a state whose conduct abroad mirrors, in miniature, the very destabilisation Nigeria itself suffers at home. Dealing with the “Prerogative State” does nothing but throw Nigeria also into the orbit of unaccountability and unilateralism.

Yet the matter is complicated by Nigeria’s actual voting record at the United Nations. A close look reveals that Nigeria has not altogether abandoned Palestine in global forums. On the contrary, Nigeria’s record over the years shows that it has consistently voted in support of resolutions critical of Israel’s occupation, with a 96 percent alignment in favour of Palestinian-related positions and only about 4 percent abstentions. This suggests that Nigeria, when placed in the bright light of the UN General Assembly, and when led by experienced diplomats at the helm of the Missions in New York and Geneva, can uphold the traditional solidarity with Palestine. Recently, Nigeria joined 142 other nations to endorse the “New York Declaration” that called for a Hamas-free Palestinian government and a renewed path toward a two-state solution. It also regularly votes in favour of resolutions demanding the protection of civilians in Gaza, condemning settlement expansions, and insisting on adherence to humanitarian law.

Where then does the sense of retreat come from? It comes not so much from Nigeria’s formal votes, but from the gap between its voting record and its public diplomacy. Whereas South Africa complements its UN votes with strong public advocacy as most recently shown by its taking Israel to the International Court of Justice (ICC), Nigeria tends to confine its solidarity to the discreet space of multilateral ballots, without matching words or visible activism. In essence, Nigeria votes right but speaks softly, and this quietude is mistaken, not unreasonably, as a retreat. The reasons for this muted diplomacy are manifold. First, Nigeria’s domestic fragility has curtailed its posture on activist foreign policy. In the 1970s, with oil revenues flowing in and buoyed by confidence, Nigeria could afford to project its voice loudly. Today, with insecurity at home, economic stagnation, and governance challenges, foreign policy activism is increasingly viewed as a luxury. The Israel-Palestinian conflict, once a moral touchstone, has slipped down the hierarchy of Nigeria’s diplomatic priorities.

Second, Nigeria’s economic and security relations with Israel have grown quietly but significantly. Israeli firms operate in sectors ranging from agriculture and technology to security. Israel has cultivated strong ties with Nigerian political and business elites, offering practical benefits that contrast sharply with the symbolic solidarity extended to Palestinians. This has introduced a “pragmatic”, almost transactional calculus into the country’s decision-making, dulling the once sharp edges of its moral positions. Third, global and regional dynamics have shifted. The so-called “Abraham Accords” of 2020, which saw several Arab states normalise relations with Israel, altered the landscape in which Nigeria previously operated. The old African-Arab consensus has frayed, and solidarity with Palestine no longer carries the same collective urgency. In this new environment, Nigeria has chosen caution, seeking to avoid alienating powerful “allies”. Yet in so doing, it has also forfeited the moral authority that once made its voice consequential.

This retreat, then, is less about formal voting patterns than about absence of visible leadership. Nigeria’s record at the UN remains broadly pro-Palestinian, but the statesmanship to match it is fast disappearing. Also, the rallying of African consensus, the convening of dialogue, the moral thunder that once made Nigeria indispensable in struggles for justice is fast fading away. The loss of Nigeria’s constructive engagement matters for several reasons. First, the Israel-Palestinian conflict remains a litmus test of global justice. For a country that has long claimed leadership in Africa and in the wider Global South, silence in the face of occupation, displacement, and genocide raises uncomfortable questions. If Nigeria cannot speak clearly on Palestine, a cause historically linked to its own anti-colonial struggles, what then is left of its activist foreign policy tradition?

Second, Nigeria’s withdrawal leaves a vacuum in Africa’s diplomacy. South Africa has sought to fill this space, most recently by pressing genocide charges against Israel at the International Court of Justice. Yet South Africa alone cannot speak for Africa. The absence of Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country and historically one of its most assertive voices, diminishes the collective force of the continent in global forums. Third, this retreat risks eroding Nigeria’s moral capital. In international politics, influence is not derived solely from military or economic power but also from the ability to articulate principled positions and build coalitions around them. Nigeria once understood this well. Its leadership in the anti-apartheid struggle, its role in ending colonialism in Southern Africa, and its activism in the Non-Aligned Movement were based on moral clarity as much as material strength. Today, that clarity is clouded, replaced by a studied ambivalence that convinces no one and inspires few. Pragmatism may be a choice, but it can never be an answer to the persistent violations of human rights and dignity.

There is still time for Nigeria to rediscover its voice. Constructive engagement does not mean hostility to Israel nor blind solidarity with Palestine. It means leveraging Nigeria’s diplomatic capital to push for meaningful dialogue, advocating for humanitarian relief, and articulating principles of justice that resonate globally. Nigeria can draw on its history of mediation in African conflicts, its credibility as a large multicultural democracy, and its heritage as a leader of the Global South. By doing so, it can once again make its voice relevant to one of the most enduring conflicts of our age. The choice before Nigeria is stark. It can continue down the path of cautious silence, trading influence for convenience, and gradually receding into irrelevance in global affairs. Or it can reclaim its legacy as a principled and constructive actor, unafraid to speak out where justice is denied. The Israel-Palestinian conflict remains unresolved, and voices of reason and moderation are sorely needed. Nigeria, if it chooses, can be one of them. In the final analysis, Nigeria’s retreat is not just about the Middle East. It reflects a broader uncertainty in its foreign policy, a loss of confidence in its global role, and a shrinking of its diplomatic imagination. For a country that once saw itself as Africa’s conscience and a defender of the oppressed, this retreat is not only regrettable but dangerous. The world has come to expect Nigeria’s moral clarity, and Nigeria owes it to itself and to history not to abandon that role.