By Adagbo Onoja

If the Kenyan writer did not die the way he did, he wouldn’t be who he is: layers and layers of mystique. Otherwise, is it another coincidence that he set on the journey of no return slightly over a month after another giant, Valentin-Yves Mudimbe, departed? Both share deconstruction of empire in Africa or, if you like, re-writing imperialism and neo-colonialism.

In fact, Ngugi is credited with originating decolonial reasoning although those who hold such a view are unjust to the trio of Onwuchekwa Jemie, Ihechukwu Madubuike and Chinweizu. Their 1983 book – Towards the Decolonisation of African Literature – preceded Ngugi’s Decolonising the Mind, published in 1986. Surely, Ngugi is a giant in decoloniality. He stands on the same level with Walter Mignolo, Quijano and the other souls who are more known for decolonial thinking.

The realm no one contests primacy with Ngugi is the question of what language African writers should write in or in which African literature may be conveyed. It remains an unsettled question but whoever or however it is settled will benefit from Ngugi’s standpoint.

Ngugi enhanced his mystique by writing Wizard of the Crow. Before the coming of that text, one had thought that Ngugi was all about anti-imperialism. With that text, he made his own contribution to the effort at demonstrating the African ontological gaze, a realm in which the Fagunwas, Tutuolas, Achebes, Soyinkas had made serious progress.

Ngugi enhanced his mystique by writing Wizard of the Crow. Before the coming of that text, one had thought that Ngugi was all about anti-imperialism. With that text, he made his own contribution to the effort at demonstrating the African ontological gaze, a realm in which the Fagunwas, Tutuolas, Achebes, Soyinkas had made serious progress.

The sore point remains why he did not win the Nobel prize on literature. The opinion that prize givers are hardly enamored of those who are too independent minded seems to say everything. Achebe and Ngugi were most unlikely to have won the prize although it is not clear if the Nobel establishment is not the loser in not finding Achebe worthy of the prize. As much as no literary text has a final interpretation, a view of Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, for instance, as a story of cultural aggression has become hegemonic across the world in a manner that seems beyond re-activation/rearticulation. It could be that the Nobel establishment is considering a posthumous award.

Ngugi might be physically dead but artists do not die. He is thus not dead. Weep not, therefore, African literary children!

Initial reactions to Ngugi’s death available to Intervention have come from the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife in Nigeria and Dr Yusuf Bangura in Switzerland

For Prof. Chijioke Uwasomba, it is a case of the departure of another and, in fact, a leading voice in the search for the reclamation of Africa and its peoples, leaving a void. It is a pity, said Uwasomba, “that those pimping for imperialism are becoming more brazen, emboldened and taking over important and strategic places in their unpardonable unpatriotic exploits against the teeming masses”

Two of the other literary giants from Africa

Professor Anyadike, a retiree from the Department of Literature in English also at Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife argues that Ngugi wa Thiong’o and a few others thoroughly understood what the real problems of Africa are in the areas of language, imperial exploitation through religion, western “education”, social inequalities, showing through their lifetime struggles that unless these deeply entrenched mental structures are effectively dismantled by Africans themselves, they will continue to be under the stranglehold of puppets of all manner of imperial schemes.

“He, like them, planted some grains of wheat which altogether are not yet doing well on the African soil”. Prof Anyadike added, asking if coming generations of Africans will be inspired by the great works the Ngugi generation have done in the fields so that “their grains become rejuvenated and take on new lives that will help Africans to liberate themselves?” He cedes the answer to tell, concluding by wishing that Ngugi’s strident voice and restless spirit remain ever green as they hunt the rascals in power to their eternal damnation! May Ngugi’s soul receive eternal transformation in the ancestral realm, he signs off.

Dr. Yomi Gidado of the Department of Sociology in the same university declares the death of Ngugi the loss of a profound, fertile literary icon by the world and critical academia, calling it another exit of another intellectual gadfly. For him, it is unfortunate that African patriots are getting depleted at a time when the forces of imperialism are becoming stronger and brazen.

From Berne comes a reaction from the Sierra Leonean political scientist, Dr. Yusuf Bangura. It reads as follows:

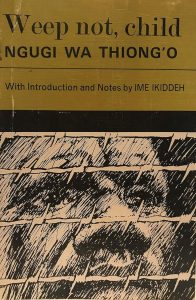

I’m saddened to learn about Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s death—one of the greats of African literature. The Nobel prize eluded him, but he shaped the minds of many young Africans.

We read his first novel Weep Not, Child for our GCE O level literature examination in 1968 at the Prince of Wales school. That novel gave us rich insights into Kenya’s oppressive system of land dispossession by British settlers and the armed struggles waged by the Kenya Land and Freedom Army, which was referred to as Mau Mau. The armed resistance paved the way for the transfer of political power to Kenyans.

Weep Not, Child also exposed us to some of Kenya’s beautiful names, such as Kamau, Njoroge, Mwihaki, Ngotho and Njeri. One of my closest high school friends (now deceased), who was at the Albert Academy, and I were fascinated by these names, developed a keen interest in Ngugi’s novels, and competed to narrate memorable lines in his books.

One section in Weep Not, Child, which I can still recall, stood out for us—Kamau’s deep pain and anger when he discovered that a girl that he was in love with was dating another man. He came out of his hiding place, where he had observed the girl intimately holding hands with her lover. Deflated, he swore to himself that he would inflict severe punishment on his rival.

My friend and I were very fond of the African Writers Series. We must have read most of the books published under the Series before I left Sierra Leone for university studies in the UK in 1971. Two other Ngugi books that we were fond of before we left the country were A Grain of Wheat and The River Between.

I also read his Petals of Blood, which was published in the late 1970s, when I was a graduate student at the LSE. Petals of Blood was a trenchant critique of Kenya’s post-colonial politics, which, Ngugi believed, failed to live up to the aspirations of the freedom fighters or deliver development.

Africa, and the literary world, have lost a profoundly imaginative, committed and fluent writer.