By Adagbo Onoja

History can get more and more complicated, especially when it is the history of the now basically dead National Association of Nigerian Students (NANS). What the history should cover and how that may be decided could be a slippery exercise. And the reception of how the history is designed can be predictably unpredictable.

Aluta has continued unabated but victory has been elusive. What then is to be done?

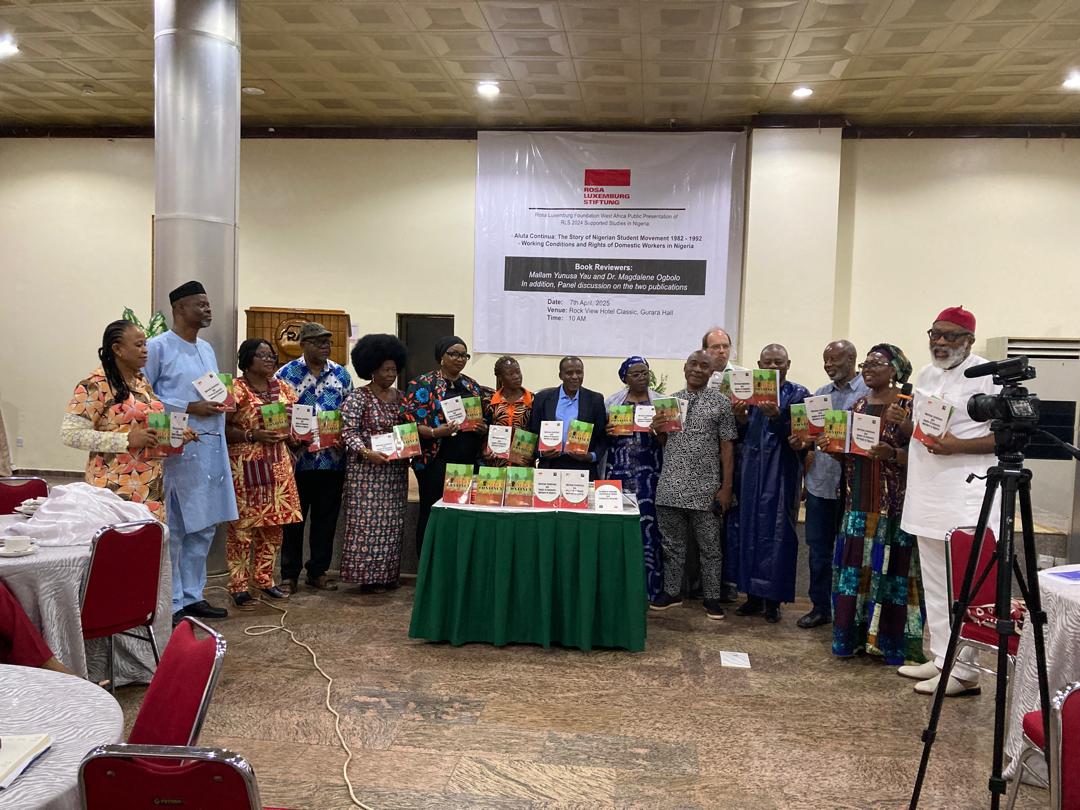

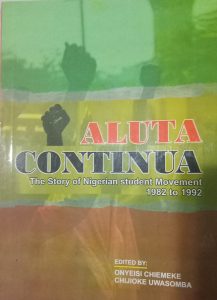

All these manifested today (April 7th, 2025) in Abuja Nigeria when a Rosa Luxemburg sponsored history of NANS was up for presentation. The text is titled Aluta Continua: The Story of Nigerian Student Movement ably edited by Lagos lawyer, Chiemeke Onyeisi and another activist, Prof Chijioke Uwasomba. It was graced by a good number of players who trace their politics to the NANS heritage. Of particular note is the presence of the female president of the student union of a Nigerian university. She is not the first female student to be. Even NANS has had a female as president but rarely do medical students venture into students’ activism. Yet, this president is a medical student.

Comrade Yunusa Zakeri Yáu, aka YZ, the book reviewer did a wonderful job of a reviewer in bringing up the merits and demerits of the efforts. Intervention is publishing his piece which brings out key aspects of the book very adequately.

There were two panelists in the subsequent session after YZ’s presentation. The panelists were Ene Obi, the activist’s activist and Dr. Saeed Hussaini, the radical activist-researcher in International Development. As a beneficiary of when the universities were universities in Nigeria, Ene Obi, predictably, lamented the degeneration of that space, declaring that “it is time for us to defend public education”.

Dr, Saeed’s contribution will attract longer attention in this review. And it is for the reason that his experience of the Nigerian educational system is that of a distant observer. He was educated outside the country and thus has a comparative radius. He considers the book timely, a bridging of the generational divide between those before and after the military. He reinforces the reviewer’s point about the potential as well as limitations in participant -observer produced texts: participant – observers can easily absolutise certain things or go hyperbolic in what they approve of or rationalise away areas of failure.

All the panelists, two per each of the books

For future editions of the book, he recommends a tendency to frame the radicalism of the students’ movement in Nigeria in the era covered by the book in exceptionalist terms when it could be even more interesting if situated in the wider continental and global trend. Similarly, he mentions how the novelty in activists writing their own history could have been much more interesting still if, in doing that, they engaged with the literature coming out from certain key figures working on the subject matter in recent times.

In future, activists telling their own story should also do well to develop the category of the PYMN, for example, with particular reference to the sociology of membership and its problematic of its gendering which YZ put a heavy stress in his review. Without explicitly stating so or in spite of itself, the book, said Dr Saeed, contributes to the question of left strategy in the 21st century, another way of indicating what can be called an unforgivable gap in the effort.

Both book reviewer and other speakers such as Dr. Saeed, of course, were on course. It is, for sure, not possible for a 282 page text to cover everything. Nor is it necessary to do so since it will never be possible to achieve a closure to the NANS story. What NANS did can be accounted for in a million different ways. As such, editors of a book dealing with the NANS subject matter must recognise that, like any other book, it is an articulatory process. The memories, the battles, the alliance/coalition politics and the agency of leadership, amongst others, that a book on NANS invokes have the potential to totalize into a meaning -action outcome beyond the imagination of the authors. As such, authors must anticipate potential ‘intellectual enemies’, figure out antagonists and its common Other and deal with them ahead or risk the text being appropriated by these same forces.

Towards another ‘The Conditions of the Working Class in England’ but this time in Nigeria

The book reviewer made reference to the disclosures on the PYMN being of no use to the DSS anymore but the DSS is not the only force writing Nigeria. There are many more powerful such interests at work and, in most cases, it is through signification that they accomplish writing Nigeria into nothingness.

This is why history, especially if it is the history of NANS, can only be a battlefront, with an eye on power relations that a highly contextualised narrativisation of that experience can produce, vis-à-vis hegemony as a strategy of empowerment and the emancipatory project. The coincidence between the position of the reviewer and the panelist is thus something to take seriously in a future edition of the book.

One way out is perhaps to search for and make a special preface of Prof Eskor Toyo’s Punch article in the event of the 1976 students’ revolt. It is difficult to find an insight into the radicalism of Nigerian students beyond the piece whose title escapes one’s memory immediately.

If there can be no closure to the NANS story, then it means this is one additional step in telling that story. The next edition should fill identified gaps and the story will continue somehow.

There is a suggestion on the ground to the effect that a media conversation on the new book be organised. That sounds a great idea because, from the way things are today, many people seem lost on what the defunct NANS stood for.

The point is to keep saluting the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation in West Africa and its managers in Nigeria for paying attention to a domain nobody else is paying similar systematic enough attention. For Aluta Continua is not the only book it presented today. It also presented Working Conditions and Rights of Domestic Workers in Nigeria. It is a sequel to a previous version, the only difference being the areas of coverage. While the previous edition concentrated on the Northwest of Nigeria, this edition took on Lagos and Abuja. It would be very interesting to see the differences between the conditions of domestic workers in largely agrarian Northwest and the key urban spaces of Lagos and Abuja. Cities are the operational base of capitalism even though there is no capitalism in Nigeria, only ‘hit and run’ accumulation style!