Adagbo Onoja reporting

It is no more only in heartland academia, if it ever was, where concern for secure knowledge is an article of faith. Other arenas of knowledge production are equally concerned with the mandate of knowledge factor in what they circulate. Sections of the civil society in Nigeria are impressively manifesting consciousness that epistemology is a fierce battleground between contending techniques since the rupturing of the turning point Rene Descartes brought to the question of how we might know that we know. Of course, Descartes made history with his Cartesian logic of knowing. But it was another tragedy of victory because while he solved one aspect of the question of how we might be sure that we know what we claim to know, he created another problem which no other thinker has been able to solve till today: Cartesian anxiety.

At the heart of the politics of knowledge production. It makes or mars a book

The university as a battleground for the truth although the problem is always the question of which of the ‘truths’

With Cartesian dualism, he gave rationalism a bridgehead in epistemology since the 16th century but only to create Cartesian anxiety: the fact that reason cannot be the basis of sure knowledge because the mind which is independent of the world cannot guarantee a secure knowledge of a world which cares nothing about the mind. With Cartesian anxiety, methodology has become a battleground such that the research technique one choses has very little to do with anything called science but everything to do with positionality or, if you like, politics. This is, arguably, the most glorious contribution of feminist contestation of patriarchy and the methodological practices that contestation has brought to the (social) sciences.

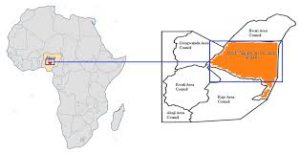

The foregoing seems to be the unspoken justification of Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s elaborate concern with quality and strength of its most recent flagship texts and the series of review of such texts with a view to improving them specifically and generally. The texts in question are Effects of Bwari Conflict and Enugu Sit-at-Home on Women by Ikechukwu Maxwell Ukandu and Nneamaka Ijie Obodo, all academics at Veritas University, Abuja; The Impact of Farmers-Herders Crisis on the Quality of Life of Women and Girls in Internally Displaced Camps in North Central Nigeria produced by four co-authors viz Ojenya Ajine Henry, Obindo Taiwo James, Enejoh Victor, & Hon. Praise MwueseTer and, lastly, Experiences and Conditions of Domestic Workers, the Role of Stakeholders and the Strategies in Mitigating Domestic Work Abuses in the North-West Region, Nigeria researched by the Centre for Gender Studies at Bayero University, Kano with the Support of Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung (RLS), West Africa

This round of the review appeared to be an exclusively Veritas University, Abuja affair. That is perhaps another way of testing the depth or otherwise of the academia in that axis of knowledge production in Nigeria. All things considered, it was not a bad outing. All three reviewers gave the three different texts impressive ratings in terms of the subject matter selection although this review has to isolate one of the texts because the issue-areas in the review are very similar.

In relation to the comparative study of the Bwari and Enugu conflicts, there is consensus among its two reviewers that, as Dr. Antewing argues, its primary strength lies in the emphasis on women, “who are often disproportionately affected by violence” and that “by centering women’s experiences, the authors fill a critical gap in Nigeria’s conflict literature, which traditionally focuses on ethnic, political, and economic dimensions without considering gender”. To a great extent, this is unchallengeable. Dr. Kelvin Ibok Anweting is of the Départment of Philosophy. Dr. Chineme Ijeoma Okafor of the university’s Department of History and International Relations and the second reviewer of the same text is no less categorical about women being “a demographic frequently unnoticed in traditional conflict analysis”. These are academically bold claims.

Beyond that, the reviewers also agree on the relevance and timeliness of the topics. So, the texts got a high score on issue selection and adequacy of treatment. Chineme goes on to credit the research report with offering what she calls a detailed study of two critical issues in Nigeria: the Bwari Conflict in the Federal Capital Territory and the Sit-at-Home protests in Enugu, South-Eastern Nigeria, framing the two as a multidimensional interaction of gender, conflict, and socio-political tension in Nigeria. According to her, the research explores how women, as individuals and as a collective, are uniquely affected by the dual pressures of conflict and systemic marginalization. And the text has thematically interrogated the origin of both the Bwari Conflict and the Enugu Sit-at-Home protests; the socio-economic, physical and psychological effects of these crises on women; the strategies employed to manage these conflicts, including their successes and limitations; how women navigate and respond to the disruptions caused by these conflicts, often developing coping mechanisms despite systemic biases.

She tells us how the Bwari Conflict is examined through the lens of ethnic and indigene-settler dynamics in Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory, highlighting disputes over land, identity, and political power, a substantially correct entry point. The Enugu Sit-at-Home protests are, on the other hand, located in the Biafran secessionist movement, exploring the socio-political grievances that continue to fuel unrest in the South-East.

Imagining life in an IDP camp!

Chineme’s pair does not challenge any of these as he too credits the research report with having effectively highlighted the gendered impacts of the Bwari conflict and Enugu “sit-at-home” orders and how the text thus offers valuable insights into the socio-economic and emotional toll on women.

The two who are of different departments in the university remain united in what they consider the observable methodological inadequacies, most of which they got right. One of this is the intersectionality deficit. While Antewing believes that a more intersectional and nuanced approach could have garnered a higher reliability and applicability of the findings, Chineme is of the view that “the analysis could have benefited from a deeper exploration of intersectionality—how factors such as age, class, marital status, or rural-urban differences intersect with gender to exacerbate the impacts of conflict. “she advances the position that questions such as whether older women or single mothers were disproportionately affected or how economic/class distinctions influence the coping mechanisms of women could have added value. Again, points on!

Common to both Chineme and Antewing is the argument by Antewing, for example, “that focus on women excludes a comprehensive analysis of how men are also adversely affected, particularly in contexts where men face heightened risks of violence or are pressured to fulfill traditional breadwinner roles amidst economic instability” For Chineme, while the report’s focus on women is commendable, the exclusion of men’s roles and experiences could be seen as a limitation in understanding the broader societal impact of these conflicts. For example, how do these events affect family structures, male partners, or community leadership?”

Antewing makes the point that there is absence of disaggregated gender data and that it undermines the depth and reliability of its findings. This is not out of place but does it really apply to this study which sets out with a focus on a specific category whose location in the class and gender hierarchy is nearly self-evident?

His second problematic moment is his observation that conflict is productive of change. He is absolutely correct to the extent that seeing only death and destruction in conflicts is a weak analysis because of the one-dimensionality. This though is easier said than done because only Marxists and poststructuralists pursue the line of reasoning that conflict is productive of change. Any academic who doesn’t subscribe to any of the two theoretical standpoints but is mouthing conflict productivity is embarrassing the mandate of knowledge. So, if we find that Dr. Antewing is neither a Marxist nor a poststructuralist scholar, we would have to interrogate him on this claim.

Epistemologically or what is historiography for historians, the most fascinating intervention in the entire review is Chineme’s argument that more primary data collection could have bolstered the study’s claims and provide stronger evidence for its conclusions. As she puts it, “there appears to be limited direct engagement with women’s lived experiences through interviews or case studies. Incorporating more qualitative data, such as firsthand accounts, narratives, or testimonials from affected women, could provide a richer and more nuanced understanding of their experiences”. This is the moment in the review, a fascinating epistemological moment because it shows a good grasp of the phenomenological character of the research and from which a deviation/deficit in terms of research techniques could be a disaster.

She could have got a 100 per cent rating with just that intervention if she did not then go on to celebrate the mixed method that she said the authors employed. But the matter goes beyond any individual academic. The point is that there is a baffling approval rating for mixed method in Nigerian academia. Methodology teachers across Nigeria celebrate mixed method and triangulation. But there is a problem with it. Mixed method is doable but there is nowhere in the text and their reviews in this round the kind of justification for mixed methods when the methods being mixed come from different ontological-epistemological roots. A post-positivist can easily convert statistical data to a discursive data but a positivist cannot convert discursive data to statistical data. In any case, positivists do not believe in discursive data. That is one level of the problem. The second and the more serious problem is that each technique is a product of its own ontology. A technique such as key informant interviews has a phenomenological root which is nonsensical to a rationalist/positivist. So, can a researcher combine statistics with Key Informant Interview or even Survey interview with its Yes/No proclivity?

Flashback to an earlier session on the books – their public presentation

Frustrated with the defeat of the positivist establishment in the United States by the post-positivist vanguard after the 2000 ‘Perestroika’ revolt, some positivists are now talking of qualitative survey. But that is not the way out. It is true that the hegemony of neo-positivism for too long made many practices to take roots or look normal. But not anymore. Why hasn’t that reflexivity acquired any momentum in Nigeria to date? After all, the questioning of the neopositivist hegemony started almost a decade before the end of the Cold War.

Frustrated with the defeat of the positivist establishment in the United States by the post-positivist vanguard after the 2000 ‘Perestroika’ revolt, some positivists are now talking of qualitative survey. But that is not the way out. It is true that the hegemony of neo-positivism for too long made many practices to take roots or look normal. But not anymore. Why hasn’t that reflexivity acquired any momentum in Nigeria to date? After all, the questioning of the neopositivist hegemony started almost a decade before the end of the Cold War.

The big surprise is how none of the reviewers made any comments on the comparability of the communal violence in Bwari with a largely women protest in Enugu State. Unless the Bwari study is adjusted in terms of focus and retitled, the comparison looks problematic. Of course, any comparison can be justified but we haven’t seen a vigorous enough justification in this case.

Rosa Luxemburg is setting standards that other civil society organisations should copy. There is no embarrassment or shame in a text being made to reverse itself in knowledge production. Some essays get dressed down, rejected or written off. Very few essays, books or treatises ever make it as a hit at the first strike. Reviews add value to it all and subjecting texts to endless criticisms, especially when they are on conflict and on women, is very important because texts are discourses and, as Foucault reminds us, discourse is the power to be seized. The author or any discursive platform which gets to produce the most consensual frame of any event, phenomenon, practice or whatever, ends up the determinant of what is normal or acceptable. And that’s the acme of power. So, knowledge production is no joking matter. It is why it is a crime against humanity to let universities degenerate by a power elite fearful of a radical studentry.

In 1986, the late Adamu Ciroma warned that if Nigeria is not careful, it would be the fool of market economy, his fear has fully come to pass. Nigeria is today the capital fool of the market economy. Similarly, if Nigeria is not careful, it would be the fool in methodology. It already somehow somewhere near that but all of that is not that manifest yet.

Listening to presentations at a recent social movement re-organisation, one couldn’t help passing a question to another comrade who should know on why the presenter speaking on social movement is also discussing choice of strategy. Doesn’t social movement politics imply a specific strategy? The fellow comrade replied that many people have stopped reading since the collapse of the USSR. He was to add later that our suffering in Africa hasn’t even started because of the knowledge gap between the continent and the rest of the world. It was a sobering confirmation of the feeling that has been most worrisome.

It is high time platforms such as Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, MacArthur Foundation, the CDD and the NPSA to get Nigeria to update herself methodologically since this is not part of the consciousness of governments in Nigeria in relation to what can make Nigeria great. Fortunately, some of the brains behind the Centre for Research and Documentation (CRD) which experimented on a version of methodological renaissance in the late 1990s are still around. Quite a number of them (Bjorn Beckman, Raufu Mustapha) have travelled far. Amina Mamman is very far away too, physically. But a number of those masterminds are not only very much in Nigeria but in Abuja. There are some individuals too, Prof Adele Junaid, for example, if we must mention name, who can lend a helping hand to the accomplishment of this very vital artery of the knowledge/power moment in contemporary Nigeria.