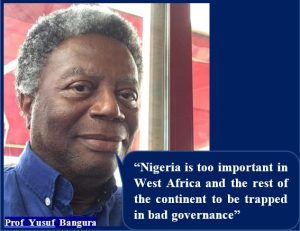

In Three Surprises From Our Two-Week Visit to Nigeria, Dr. Yusuf Bangura represented Nigeria as an expanding or growing economy. He got a lot of interesting responses to which this article is a response, including one of the commentators whose piece is published under Bangura’s piece here:

Thoughts on approaches to the study of Nigeria (and Africa generally)

The author in a file picture

By Yusuf Bangura

I want to share a few thoughts on Toba Alabi’s interesting essay calling for a new approach to the study of Nigeria and Africa in general, using my reflections on our recent visit to Nigeria as an anchor.

I’ve been impressed by the strong interest and largely positive reactions that my travelogue has generated, especially among Nigerians. I’ve received or seen more than 30 responses to the essay.

Interestingly, my 22-page academic paper on Nigeria’s troubled politics and development, which I first circulated after the Nigeria trip, has not elicited anything close to the reactions I’ve received on the travelogue, even though I consider the academic paper more thoughtful, empirically- grounded and pointed than the travelogue.

Is this an indication of Nigerians’ weariness with articles about the country’s debilitating politics? Or is it a general reluctance by many readers to engage academic pieces, which are usually fairly long and complex?

Surprisingly, one of the few responses I received on the academic paper was from a director of a public policy institute in Sierra Leone, who described it as ‘mind-blowing’ and wanted to organise a seminar for me to present the paper in Freetown to ‘elites .. across the regional and ethnic divide.’

The interest from Sierra Leone is instructive. Sierra Leone’s ethnic politics is just as divisive as Nigeria’s. The big difference, however, is that Nigeria has, over the years, crafted a number of policies to de-ethnicise its politics, even though the outcome has been poor for reasons that I address in the paper.

The pitfalls of one-dimensional frameworks for understanding societies

Toba Alabi is on point in drawing attention to the need for multidimensional or dialectal frameworks for understanding change and development.

A retired professor in a village at Sapele, who welcomed me as Head of the Department of Political Science when I first arrived at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria in 1980, and under whom I served as Vice President of the Nigerian Political Science Association in 1984-86, sent me a useful response, drawing attention to the general regression in his village and elsewhere on the continent and the challenges social scientists will face in addressing both widespread dysfunctions and small progressive changes in their frameworks of analysis. He asked a pointed question: will social scientists be objective in carrying out such research? He seemed unconvinced.

Reports on Nigeria and Africa often tend to be driven by two one-dimensional approaches. The first is an afro-optimistic approach, which focuses only on the good things going on in Africa and takes umbrage at those who address Africa’s shortcomings.

As I reported a few days ago, one of the two critical comments on my travelogue (someone in the diaspora) accused me of being a victim of afro-pessimism for using the word “surprises” that he believed doubted Nigeria’s developmental abilities.

As a retired professor of economics in Abuja told me in a WhatsApp message, my surprise at the three developments was because I didn’t expect the changes that we saw to have happened so quickly, especially the digitalisation of large parts of the economy. To the diaspora critic, however, Nigeria has always been a great country and it is Western afro-pessimists and African intellectuals whose minds have been poisoned by Western propaganda who fail to recognise Nigeria’s abilities and achievements.

A longer critique from a friend in Abuja, with whom I had four rounds of exchanges, branded the changes I highlighted in the travelogue as insignificant, and wanted me to focus on Nigeria as a failed state. He even sent me a 2011 report by five colonels of the US Air Force at the American Air University on Nigeria as a failed state (which, incidentally, divided Nigerians on social media when it was first released) and a BBC report on banditry in Zamfara State.

Anyone who has been following reports in Nigeria should be familiar with this negative view of Nigeria among large sections of the populace, especially on social media. My 22-page academic paper that I referred to earlier copiously addressed this issue.

There is a lot to be angry or dislike about Nigeria. In that paper, I traced and analysed the causal links of three issues that I believe are responsible for Nigeria’s dysfunction at the political level: identity politics, underdevelopment or limited structural change, and the rentier character of the state. Identity politics frustrates the development of a civic culture of shared values and ability to hold leaders to account across ethno-religious divides. Underdevelopment weakens the development of social forces that may transcend ethnic identities and promote voter autonomy and work-based and civic interests. And rentierism generates high levels of corruption or transforms politics into a game of elite competition for rents or pilfering of public resources, leading to exclusionary patronage networks. Kidnappings, violence, large scale corruption, massive oil theft, poor leadership, stunted industrialisation, high levels of vertical and horizontal inequalities, and dramatic declines in living standards, following the devaluation of the naira and spike in inflation, are real and serious. So, a lot of what afro-pessimists, or those not optimistic about Nigeria, complain about is important and demands urgent attention.

However, my problem with afro-pessimists is, like their polar opposites (afro-optimists), they are wedded to a one-dimensional view of Nigeria. To them, Nigeria has either failed or is inexorably on the path of collapse.

As a friend of who directs a research and advocacy centre in Zaria told me, if I had adopted a failed state perspective, we would have ignored or wouldn’t have seen the three changes I addressed in the travelogue. Another friend and professor with a track record of good public service thanked me “for drawing our attention closely to what we see daily but often ignore or refuse to truly admit it”.

I’ve closely followed the literature on crisis or failed states. Our Institute (UNRISD) had many projects on this topic when I worked there. The concept of failed states made a lot of sense when, in the 1990s, states in Africa, such as Somalia, Sierra Leone and Liberia, as well as elsewhere experienced total breakdown or failure. However, the concept ran into trouble or became slippery and imprecise when all kinds of states that are bedevilled by insecurity are referred to as failed states.

Although Nigeria must sit up, a failed state implies the complicity of successful state(s) since none is meaningful without the other

The US has one of the highest number of homicides in the world and large parts of its inner cities are ungovernable, but no one describes the US as a failed state. Similarly, cities in countries like Brazil, Mexico, Columbia, Jamaica, Trinidad and South Africa are blighted by kidnappings and gang violence, but they are not referred to as failed states.

Interestingly, whites in South Africa under apartheid had a solution to widespread insecurity: they structured urban areas into segregated settlements. This restricted urban violence to a black-on- black phenomenon in highly deprived townships. It insulated white people and their brutal control of the country from widespread violence. The African National Congress has not changed this obnoxious situation despite 30 years of black rule. The emerging black middle class is fully ensconced in exclusive safe areas.

A fairly similar situation of segregated settlements is emerging in Nigeria where elites live in large and highly secured gated communities or estates. Abuja, the capital, is the city of estates par excellence. Elites have also abandoned the unsafe intercity roads to the poor. Most now fly to avoid kidnappers in violence-prone areas.

Small but qualitative changes can contribute to radical and systemic change

We saw three developments occurring in Nigeria during our visit that acted as a reality check on the narrative of afro-pessimists: an emerging and thriving food processing sector that is linking primary agricultural producers and industrialists; an incredibly rapid digitalisation of large parts of the economy that has incorporated many traders in the informal sector and ordinary consumers who were hitherto excluded from the formal banking system; and a vibrant music scene that is overwhelmingly local and has crowded out Western music. We may also add here the film industry (Nollywood, kannywood, and Yoruba movies) and fashion. The speed with which Nigeria has transitioned to a digital economy is really mind-blowing. A high school and university friend, who is now a retired professor at Idanre, made this comment when he read the travelogue:

“You drew my attention to the innovations in the banking sector, ..which many of us have taken for granted. For instance, because of my health situation, I have not been to any bank in almost two years, but I’ve been transacting business seamlessly since I have a valid debit card and NIN.”

These may be small steps, but no one who understands development will dismiss them as insignificant. My feel for political economy always pushes me to look for counter pressures, tendencies or trends that defy a norm, when analysing development or social change. It’s a terrible mistake for scholars and activists who are concerned about transformative change to ignore small but progressive changes in the economy.

There’s a reason why the German revolutionary, economist and philosopher, Karl Marx, wrote three volumes of Das Kapital in his study of capitalism and effort to craft a revolutionary thesis on the emancipation of the working class. In those three volumes, he laid bare the internal logic, contradictions and dynamics of capitalism that he believed will lead to its demise and birth of a higher economic, social and political order, which he called socialism. Marx saw capitalist development as a progressive force for two main reasons. First, capitalist revolutions in Europe destroyed the privileges of feudal classes and their reactionary culture and hold on society. And second, capitalist growth enabled the expansion of the working class, which would spearhead the anticipated revolutionary change and humanisation of society.

Even though capitalism wasn’t well developed in Russia when the Bolsheviks embarked on their revolutionary struggles in the late 19th century, their leader, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, went to great lengths to look for sprouts of capitalism that he believed had the potential to create a home market and a formidable working class in his The Development of Capitalism in Russia. We now know that building socialism in countries that have not made significant progress in capitalist development, as Russia did, may produce high levels of repression and authoritarianism.

Marx took for granted the progressive role of capitalism in creating a home market and expanding the productive forces. Focusing largely on the metropole, he did not foresee the emergence of agents or compradors in poor countries that help the growth of capitalism in Europe and retard development in their own countries. It was left to Marxists working on non- Western or developing countries to broaden the perspective on how capital behaves in different settings. It was clear that a large section of capital in poor countries was not in production, but floated as middlemen, traders and agents of foreign capital, which sucked surpluses or capital out to the metropole. A distinction was, thus, made between progressive industrial capitalists and reactionary middlemen or comprador capitalists that collude with foreign capital to stifle development in the global South. Neo-Marxists sided with local industrialists in developing the productive forces against the comprador class or middlemen while pushing for radical social change.

However, some Marxists who were obsessed with North-South inequalities and dependency, focused almost exclusively on comprador capitalists, and saw capitalism in the global South as incapable of developing the productive forces. Far-reaching industrialisation in East and South East Asia dealt a serious blow to this view of capitalism in non-Western societies. And globalisation, which coincided with the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, ushered in a production regime of global value chains, in which several parts of a product can be produced in many countries, especially in the global South, as transportation or containerisation became cheap and industrialists look for cheap labour overseas. Fast-growing China and India, previously closed or semi-closed economies, took advantage of the development and thrived.

However, some Marxists who were obsessed with North-South inequalities and dependency, focused almost exclusively on comprador capitalists, and saw capitalism in the global South as incapable of developing the productive forces. Far-reaching industrialisation in East and South East Asia dealt a serious blow to this view of capitalism in non-Western societies. And globalisation, which coincided with the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, ushered in a production regime of global value chains, in which several parts of a product can be produced in many countries, especially in the global South, as transportation or containerisation became cheap and industrialists look for cheap labour overseas. Fast-growing China and India, previously closed or semi-closed economies, took advantage of the development and thrived.

As a friend in Abuja, who was previously a union activist and now runs a research, policy and advocacy centre, reminded me during a conversation we had on Dangote’s refinery, when we advocated radical social change or socialism in Nigeria in the 1980s, we saw industrialists as allies against the “comprador bourgeoisie”. We theorised the marriage between comprador forces and foreign capital as antithetical to the development of the country’s productive forces and the working class, but felt that the development of a strong local industrial class could build the right relationships and networks globally to transform the Nigerian economy.

Nigeria’s structural adjustment programme in the 1980s had a heavy toll on the working and middle classes. But when we researched it, we didn’t just moan about its devastating effects on living conditions and a dysfunctional polity. We also studied counter tendencies and forces that we believed would move Nigeria forward. Our writings in that period focused largely on the adjustment programme and working class power through their unions because they were a powerful force in the country.

We strongly believed that workers and their unions were central to the creation of a better

Nigeria. Some of the key texts that I wrote during that period are:

* ‘The recession and workers’ struggles in vehicle assembly plants: Steyr Nigeria’ (Review of African

Political Economy. Vol. 14, Issue 39. 1987);

* ‘African workers and structural adjustment: with a Nigerian case study’ (with B. Beckman, in

*A. Olukoshi (ed.) The Politics of Structural Adjustment in Nigeria. London: James Curey. 1993);

* ‘IMF/World Bank Conditionality and Nigeria’s Structural Adjustment Programme’ (in K. Havnevik (ed.) The IMF and the World Bank in Africa: Conditionality, Impact and Alternatives (Uppsala: Scandinavian Institute of African Studies. 1987);

* …‘Structural Adjustment and De-industrialisation in Nigeria: 1986-1988’, (Africa Development. Vol. 16, No.2. 1991); and

* ‘Intellectuals, Economic Reform and Social Change: Constraints and Opportunities in the

Formation of a Nigerian Technocracy’ (Development and Change. Vol. 25, Issue 2. 1994).

Understanding how the economy worked, including areas of strengths and limitations, were central to our framework in studying the heavy toll of the structural adjustment programme on workers, the middle class and the wider population generally.

Bjorn Beckman and Gunilla Andrae also used this multidimensional or dialectical approach to study the problems of the textile industry, the coping strategies of industrial firms as they sourced their raw materials locally, and the kinds of bargaining institutions or pacts that textile unions formed with industry bosses to stem the decline of the textile industry in their Union Power and the Textile Industry and Industry Goes Farming. Bargaining produced a labour regime that stabilised the hitherto massive retrenchments and improved the conditions of the workers.

In search of younger researchers on this theme

Conclusion

The working class and unions face serious problems today because of identity politics and decimation of their numbers. Still, they remain an important part of the solution to Nigeria’s problems. However, focusing only on workers’ struggles, or elite politics and insecurities or state failure, without understanding the small but significant changes that are occurring in the economy is patently uninformed scholarship, which may produce blind activism and bad politics.

The need to look for counter-tendencies to bad practices and outcomes raises the following question: how can the Nigerian central state, which everyone complains about, be disciplined? It seems to me that there are three counter pressures to the debilitating norms associated with the central state: organised popular pressure through voice and mass collective action; actions in a core set of sub-states that set new norms of governance that can have spillover effects on other states and the central state itself; and pressures from industrialists concerned about the negative effects on business of instability and uncertainties associated with divisive politics, poor management of the macroeconomy and fantastical stealing of public resources.

Disapproval of central state practices has been more pronounced at the level of voice than in sustained mass collective action. And the loudest voices have come from those advocating a restructuring of the federal state that will lead to some kind of confederation. Among these calls are those who advocate a return to a confederation of regions. In the academic paper, I dismissed these calls for a confederation of regions as misguided. This is because a confederation of region works against the logic of fragmentation that helps multiethnic societies to avoid systemic polarisation.

As I explained in the paper, insights from the study of ethnic structures and governance suggest that identity may become a problem when it is articulated within a polarised ethnic structure of two or three groups or clusters; or one in which two, three or four large groups coexist with a large number of small groups, leading to a few power blocs or coalitions that may limit the scope for bargaining. The best geopolitical structures to aim for are those in which there is a high level of fragmentation as in Tanzania, or cases in which one ethnic group is overwhelmingly dominant, as in Botswana. Nigeria should expand the universe of political units that are used for ethno- regional and religious claims-making—not limit them, as happened in the First Republic, which led to a civil war. These issues are fully discussed in the paper.

The second counter-pressure, good governance in a core set of sub-states that will have ripple effects on other states and the federal centre, has been hampered by the inability of most states to generate revenues internally. Only Lagos state seems fiscally viable among the 36 states: it was able to internally generate more than one billion dollars in 2022 (N651.2 billion at an exchange rate of USD1=N450) before the massive devaluation of the naira in 2023. The second highest ranked state, Rivers, in internally generated revenues, raised only 26.5% of Lagos’s revenues. Nineteen states could not generate even USD50 million dollars from domestic taxation in 2022; such states may not be viable without handouts by the federal government from the oil rents.

The third counter-pressure is industrial capital. I singled out the food processing sector because that was what we were able observe in the limited time we had. Reports suggest that half of the workforce in Nigeria’s manufacturing sector are in food processing. That sector, which has strong backward linkages with agriculture and the peasantry, needs to be studied since it is one of the sectors in the economy that shows strong signs of growth and transformation.

My obsession with small but meaningful changes at the level of the economy is not restricted to Nigeria. When we visited Uganda in 2023, we saw a vibrant country, with an energetic, young population but mostly, as in Nigeria, involved in basic survival activities, and a limited or stunted industrial landscape.

We decided to look for hidden but innovative activities that have the potential to add value to, and transform, the economy. Our search took us to the banana plant, the base for amatooke, Uganda’s staple food. Uganda consumes more bananas than anywhere else in the world, and, with 84 varieties of the fruit, is the second largest producer after India. We discovered that the banana plant is useful not only for food; its stem contains fibre that can be processed to make carpets, bags, hair extensions, clothes, sanitary pads, shoes and various other household items and crafts. We read and were informed by the manger of the fibre factory we visited (Texfad) that many small companies are now involved in the manufacturing of these fibre-based products, some of which we examined at the factory. But manufacturers faced serious limitations: inadequate investments, problems of scaling up production techniques and low output. Lack of effective industrial policies at the state level has facilitated a massive inflow of second hand products (or what Ghanaians aptly call in Twi oburoniwaawu or ‘the white man is dead’) and cheap Chinese imports. I wrote a piece on this experience, titled Banana Fibre: Key To Uganda’s Industrial Development?, during our transit in Amsterdam from Entebbe, and was published online in the Ugandan New Vision newspaper.

The development of a home market is very important for industrialisation and growth of the working and middle classes. Industrialists have a vested interest in expanding the productive forces and taking on comprador interests that have stifled Nigeria’s growth. Their success may fire up similar changes in the rest of the economy and, ultimately, may be beneficial to workers and unions in their collective action demands. What’s happening in the three areas that I addressed in the travelogue should feed the anger for change at the political and economic levels.

The author wrote from Nyon, Switzerland

Bangura and wife in an outing but far away from Nigeria this time!

Yusuf Bangura’s Visit to Nigeria: A Call for a New Paradigm in Assessing Africa’s Development

By Toba Alabi. (tobalabi@yahoo.com)

Africa is often portrayed through a lens of challenges, overshadowing the nuanced realities of progress and resilience that define many of its nations. Nigeria, the continent’s most populous country, is no exception to this skewed narrative.

However, during a recent two-week visit to Nigeria, Yusuf Bangura, a distinguished scholar and keen observer of African development, encountered a country teeming with transformation, innovation, and cultural dynamism.

His observations challenge the prevalent academic discourse that focuses predominantly on Africa’s struggles, calling for a paradigm shift that emphasizes progress, potential, and the untapped opportunities driving socio-economic change. From a thriving local food processing industry to the rapid adoption of cashless transactions and the global rise of Afrobeats, Bangura’s experiences highlight a Nigeria that defies stereotypes and demands a re-evaluation of how its development story is told.

Who is Yusuf Bangura?

Yusuf Bangura is a renowned scholar and intellectual from Sierra Leone, widely recognized for his contributions to political economy, governance, and development studies. A former Research Coordinator at the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD), he has authored and edited numerous publications addressing critical global issues such as inequality, democratization, and social policy. Bangura’s work often examines the intersection of politics and economic development, emphasizing the importance of inclusive policies for sustainable growth. His critical insights have significantly shaped academic discourse and policy-making in Africa and beyond.

Beyond his academic achievements, Bangura has been an advocate for social justice and equitable development, particularly in the context of post-colonial African states. His commitment to evidence-based research and his ability to blend theoretical rigor with practical relevance have made his work influential among policymakers, scholars, and civil society actors. Through his writing and advocacy, he continues to inspire efforts to address systemic inequalities and promote inclusive development globally.

Reflections on Nigeria’s Transformation

Bangura’s visit to Nigeria showcased a nation in the throes of multifaceted transformations. The proliferation of local food processing enterprises, which not only boost agricultural output but also create employment, underscores a deepening industrial base. This sector’s growth exemplifies Nigeria’s ability to leverage its natural resources for economic advancement.

Additionally, the implementation of cashless transactions highlights the nation’s technological evolution. In urban and rural settings alike, mobile banking has reshaped the economic landscape, fostering financial inclusion and efficiency in commercial activities. Such progress is emblematic of a broader African trend toward digitization and modernization.

Culturally, the global ascendance of Afrobeats has positioned Nigeria as a powerhouse of creative expression. Artists such as Burna Boy, Wizkid, and Tems have not only garnered international acclaim but have also redefined Africa’s image on the global stage. This cultural export is a testament to the power of African ingenuity and resilience.

Rethinking Academic Narratives

Yusuf Bangura’s observations raise critical questions about the frameworks used in assessing Africa’s development. Traditional academic paradigms often center on deficits—poverty, corruption, and underdevelopment—without adequately acknowledging the strides made by African societies. This approach perpetuates a one-dimensional perspective, failing to capture the continent’s vibrancy and potential.

Bangura advocates for a more balanced narrative, one that celebrates Africa’s achievements while critically analyzing its challenges. He emphasizes the importance of recognizing grassroots innovations, entrepreneurial resilience, and the socio-cultural shifts redefining African identities. By doing so, scholars can provide a more accurate and constructive understanding of Africa’s development trajectory.

The Way Forward

To align with Bangura’s call, there is a need for collaborative research that bridges local insights with global academic discourse. African scholars, in particular, must lead the charge in redefining narratives about their continent, ensuring that these stories reflect the complexities and opportunities of their societies.

Furthermore, policymakers and development practitioners should draw lessons from successful local initiatives to inform strategies that drive inclusive growth. By focusing on strengths and potential, Africa can inspire solutions to its challenges, leveraging its rich human and cultural capital.

Conclusion

Yusuf Bangura’s reflections on Nigeria illuminate a nation on the cusp of profound change. His observations serve as a reminder that Africa’s development story is far more intricate than the conventional narratives suggest. By adopting a paradigm that values progress alongside challenges, academics and policymakers can better capture the essence of a continent brimming with possibility and promise.

Toba Alabi is Professor of Political Science and Security Studies. (08036787582)