On December 12th, 1984 starting from 4 pm at the University of Lagos, Prof Anthony Asiwaju, then the Dean of the university’s Faculty of Arts, delivered an Inaugural Lecture crisply titled Artificial Boundaries. On December 12th, 2024, the Inaugural Lecture was exactly 40 years old. The octogenarian sat down with Intervention in what he called a ‘special evening’ to recall that day and what followed, particularly the terrifying invitation from Dodan Barracks two days after the Lecture and his meeting with General Tunde Idiagbon, the Chief of Staff, Supreme Headquarters at the time and deputy-Head of State to General Muhammadu Buhari.

This reportage takes the trip into history that the 5-hour long encounter between Asiwaju and Intervention turned out to be, including the less than an hour devoted to the dinner that ended the day. At the end of it all, it could be comfortably asserted that everything about Prof Anthony Asiwaju speaks to chance, unpredictability, incalculability, non-linearity and indeterminacy. For instance, the man did everything to escape going beyond a first degree but only to end up a ground breaking Historian. This is in spite of the initial hitches, including not being able to find a topic to research for almost a year after finally registering for a PhD at the University of Ibadan on December 17th, 1966. He is thus what he is today – an Emeritus Prof of African History with bias to Border Studies – only because of the chaotic nature of how the world works. Put another way, the story of Prof Asiwaju justifies everything postmodernist historiography claims: history as the unfolding of chance and chaos: totally non-linear, indeterminate, hardly plannable and multi-layered. Now, the news -in- full, with the Idiagbon segment coming last because Intervention is approaching the narrative from the sequence of occurrence.

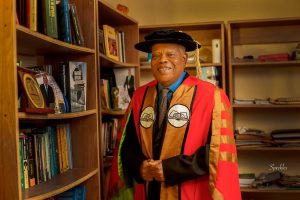

Emeritus Professor, Anthony Asiwaju being interviewed by Intervention’s Editorial Associate, Adagbo Onoja (edited out of the pix) on Dec 12th, 2024

Me Study for a PhD? No! No! No!.

The Enlightenment challenge to the monarchy in Europe had been but only a partially successful revolt. Religion which was attacked along with the monarchy has remained a key actor in world affairs, particularly Christianity in Africa. One sphere Christianity succeeded in stamping its authority has been the educational sphere. In what is today Western Nigeria, one way of enacting religious penetration was/is capturing ’em young. One of the brilliant minds successfully so integrated then is Anthony Asiwaju. He served as a teacher at St Mark’s Teacher Training College in Iperu Remo from where he went to the happening university at the time: the University of Ibadan. 1963, the year he got in was the 1st anniversary of the re-designation of Ibadan as an independent university. As everyone knows, it was the University College Ibadan, a campus of the University of London before that moment. After three years, he got a degree in History and went to teach at Our Lady of Apostles Secondary School, Ijebu – Ode where he had been teaching for his vacation jobs in the undergraduate days. Having gone to the university with an additional scholarship from the Lagos Archdiocese then on the recommendation of Rev Father Anthony Salisu Sanusi, the then Catholic Education Secretary for Western Region, the prospect of rising to the position of a Principal in any of the numerous Catholic owned secondary schools was building up in his mind.

Then things began to happen, much of them over and above his head. The first to happen was the granting of university scholarship to four of the best graduating students in History out of the ten of them who obtained Second Class Upper Degree. First Class was unthinkable at UI then, partly for colonial reasons and partly for some empirical reasons. Before anyone could say scholarship, the three others had resumed in October1966. Jide Oshuntokun was one of them. Asiwaju was nowhere to be found. Tongues were wagging. It got to a point he himself felt the need to go and rationalise why he had no plans to leave his teaching job in Ijebu Ode to pursue PhD. Apart from the burning ambition to ascend the position of the Principal of the secondary school, he also thought that it was a set up by some bad guys to show him up as a not so intelligent material vis-a-vis a PhD. It wasn’t that he wasn’t brilliant. it was that he was not someone who went about demonstrating his trigritude. Otherwise, he had demonstrated top scores ever since in History up to undergraduate. There were just no reasons for him to panic or doubt his competence. He had probably been reading too much to Shakespeare’s caution that certitude is the chiefest enemy of security. Anyway, off he went to Ibadan to undo the attempt at dragging him into a PhD programme.

It was to Prof Emmanuel Ayandele he went. Ayandele, arguably most noted for his book, The Educated Elite in the Nigerian Society had been slated to be his PhD supervisor. The narrative he crafted and unleashed on Ayandele was, in his view, failure proof: he undertook his First Degree on the sponsorship of the Catholic Church. It is ethical on his part to fulfil the bond in order not to create a bad impression that could block such an opportunity for others. It was delivered with the astuteness of a determined actor. Unfortunately for Asiwaju, the narrative received a different interpretation from Ayandele. Ayandele who took a sympathetic view of Asiwaju’s narrative took the case to Prof J. C. Anene, the then Head of Department for History at UI then. The twosome were each other’s darling. Ayandele told Anene what was happening, obviously from the point of view of how the matter could be resolved in favour of Asiwaju. Both of them had no idea that Asiwaju crafted the narrative to achieve the agenda of avoiding going for a PhD.

From that moment and unfortunately for Asiwaju, his narrative was turning performative. Anene, a Catholic, worshipped at the Seminary in Bodija where Reverend Father (later Bishop) Anthony Salisu Sanusi, his school mate at Trinity College in Dublin, also worshipped. Predictably, Anene took up the case with Rev. Fr Sanusi one morning after the Mass service, telling the Reverend Father about one of their students who did so well in his 1st Degree, had been offered scholarship but under a bond with the Catholic Church and is, for that reason, unable to take his place. Fr Sanusi who knew Asiwaju much, much earlier since their Iperu Remo days shot back: ‘I know him very well. I am going to release him’. Of course he knew Asiwaju very well as already indicated earlier. What he didn’t know was among the top performers in his set and had got a scholarship to proceed for a PhD. The next day, Asiwaju found himself being asked by the driver to Fr. Sanusi to meet the Rev Fr in the Principal’s Office. Sanusi had driven to Ijebu-Ode from Ibadan to effect his release a day after the chat between him and Prof Anene at Church the day before. As Asiwaju sat outside the Principal’s office waiting for his summon, he could hear both Fr Sanusi and the Principal, Rev Sister John the Baptist laughing heartily, suggesting an easy consensus among them on his release. He was right. That was the decision communicated to him when the two of Sanusi and the Rev. Sister came out of the Principal’s office to meet him waiting. The point, he was told, is that if the Catholic Church had its own intellectuals like him, they could rub places with the Kenneth Dike (who is an Anglican).

End of the road for Asiwaju’s determination to dodge a PhD? Not yet. The aspiring Principal hit on the idea of buying time by inventing another narrative. This time, he told the Principal it would be so unfair for him to leave immediately as he was permitted to. That would amount to abandoning the students he had been teaching. But the Principal argued to the contrary. She said the session was almost over and Asiwaju’s departure at that point wouldn’t be such a problem. This was when he gave up, feeling fully cornered. So, to Ibadan he went to undertake a PhD.

But to Study What?

But to Study What?

When he met Prof Ayandele as the supervisor, he was told what new PhD students are usually told: go and read widely. The assumption is that by reading widely, a student will come upon something that has still not been fully explained and which s/he might be interested in working on so as to fill the gap and thereby make his or her own contribution to knowledge. The question was how long was he going to be reading and reading in which area exactly.

There was a good friend of his in the PhD programme, Wale OyeMakinde, who had settled on labour in the railway system. It occurred to Asiwaju that he could take on roads history, since someone was already doing something on the railway. Even that wasn’t coming off, partly because there is no one road system as in the case of the rail system. The idea that if going forward is impossible, going backward shouldn’t be so was becoming attractive to him.

But something else then happened. Prof Ade Ajayi, the new Head of History Department, sent for him. The meeting was not one between a HoD and a graduate student but one between an established historian and an emerging but still unclear historian. The HoD asked how far he had gone. Asiwaju told him how he started exploring a research question on roads history but which had stalled.

Why don’t you try studying British administration in Egbado, Ajayi asked. To be different from others who did their PhD on British administration in different areas in Nigeria, do British administration in Egbado Division and compare it with French administration on the other side which is what was Dahomey, Ajayi continued. At last, the unclear historian was on his way. The archival works started. But his level of mastery of French language was nothing to write home about. So, he needed to go back to Ajayi. This he did with an amendment to the Ajayi topic. He would rather do a comparative study of British rule in Egbado and Ekiti. Ekiti is one sub-ethnic group but a 16-kingdom affair. He considered this to be more like it than comparing British and French rule in two different colonial spaces. He argued how another student who was also given the topic of researching British rule in Egbado and French rule in Ketu (in Dahomey) not only abandoned the topic but also abandoned academia altogether.

Ajayi confirmed that a student did run away from the topic but argued that it was partly the case that the student in question had no minimum French language usage. In any case, the student who ran away is unlike Asiwaju whose father is from the other side. Other side was a reference to ancient Ketu where Asiwaju’s father came from but which fell under French colonialism while his mother side fell under British rule in what is today Nigeria. This background, argued Ajayi, meant that Asiwaju had a ready-made advantage in terms of collecting data over there.

Asiwaju was nabbed, more so that a departmental car and driver were put at his service to undertake the Ketu segment of data collection. When he came back, he was completely decided on a topic: “The Yoruba Astride Benin Border Under British and French Administration”.

Imagining the Reluctant PhD Student Starting on a History Making Note

Imagining the Reluctant PhD Student Starting on a History Making Note

The title of his thesis topic meant that he was starting on a history making note. Indirect rule had emerged the thematic corner stone of the Ibadan School of History. Adiele Afigbo had pioneered study of British colonial impact by looking at the monarchisation of Igboland through the warrant chiefs arrangement. His PhD and that of Murray Last (now at University College London) on the Sokoto Caliphate inaugurated independent UI PhD after it delinked from the University of London. Afigbo’s thesis and Last’s as well were landmark because they were all within the logic of the nascent Ibadan School of History marked out by its epistemological rebellion against European historiography.

It was a no mean achievement Ibadan in the context of the binary crisis of Western metaphysics and its relation to Africa as a case of a fall from grace off Europe and a space out of history, good for nothing else than being occupied. Articulated as such by leading European philosophers, particularly Kant, Hegel, David Hume and practicalised by colonial officials, African History was ruled out of the question. This was the hegemonic frame that what became the Ibadan School of History challenged and dismantled. And it did this so beautifully by staging the contestation from the intellectual and administrative headquarters of Empire. While Kenneth Dike was leading the assault from London, Saburi Biobaku was shelling from Oxford where he wrote a PhD thesis titled “Egbas and Their Neighbours”. The Oxford establishment could neither classify the thesis as European History nor could they call it African History since Trevor-Roper, Oxford’s Professor of Modern History, had dismissed African History because, according to him, Africa is about darkness and darkness is not a subject of History.

Biobaku and the other radicals wrote what were strange to British imperialist history. It was their struggle that eventually led to the birth of African History as a sub-discipline. Their argument was simple: evidence in African History must be based on data or sources from below or from African people or it will still be history from the top which had nothing to do with the African specificity. That way, what later became Ibadan School of History achieved forcing historical research based on archival and oral tradition into historiography. This was what made History to become multi-disciplinary because, to do oral history, the History researcher must tap from linguistics, archeology, anthropology, ethnography, ethnology, colonial intelligence reports/archives.

Intervention can assert that it is in this sense that Ibadan School of History can claim credit for contemporary ideas of decoloniality and, to a great extent, the idea of qualitative research techniques. Tragically, neither the country nor the University of Ibadan is today in a position to assert and defend authorship of these radical methodological innovations long before they became popular. Yet, it was a life time national achievement.

The Ibadan School of History Kenneth Dike laid the foundation with his trade and politics in the Niger Delta which was, however, in London, just like Biobaku and Ade Ajayi although Ajayi was on the Christian mission in Nigeria and its impact. Obaro Ikime studied ‘Itsẹkiri-Urhobo rivalry under the British in the Niger Delta. Philip Igbafe did on Benin under British administration while Joseph Atanda took care of New Oyo Empire. Adeleye took off from Last by studying power and diplomacy in Northern Nigeria while Banji Akintoye was on the same topic in Yoruba land.

What Asiwaju’s topic did was to shift the concentration from British indirect rule to a completely new theme in African History by looking at Western Yoruba under British and French colonial rule and then expanding that to partitioned communities or cultural groups across Africa subsequently. That is the distinctiveness of his focus, making him a darling of Ade Ajayi as well as Michael Crowther who examined his thesis. Crowther was then at Bayero University, Kano from where he subsequently moved to what is now OAU, Ile-Ife before finally landing in UNILAG and becoming a colleague of Asiwaju. It is not clear what is the state of African History today across the universities across Nigeria!

The late Gen Tunde Idiagbon

Buhari/Idiagbon, Asiwaju and Border Studies Cum Policy

Mercifully, systems die hard. The Ibadan School of History may be down but it is not out. It did produce scholars who brought growth to it. Prof Asiwaju is a good illustration of a claim of growth. He exploited the epistemological logic of the School to create Nigerian scholarly exploration of the border. There’s no review of literature on that field anywhere in Nigeria today that would not start with his key texts on the field. Several decades before border studies established itself most firmly in the post-Cold War, Asiwaju had struck. He had not just attained the rank of a Professor of African History after completing his PhD in 1971, he delivered an Inaugural Lecture that echoed in Dodan Barracks, Nigeria’s seat of power then and the tension that came with that.

UNILAG had a culture of advertising its Inaugural Lecture series in the national newspapers. Asiwaju’s was no exception. From there, the intelligence service – the NSO then – picked up the information. At a time when the Federal Military Government had closed the borders, the topic of the Inaugural Lecture had become a sensitive one. So, two NSO operatives landed on the campus two days before the lecture and headed straight to the VC’s office. Prof Akin Adesola was UNILAG’s VC then. But Adesola told them he doesn’t see advance copies of Inaugural Lectures and that the only way they could obtain a copy of the text is perhaps to see the lecturer concerned. Whether they believed him or not, they left to look for the lecturer, landing in Asiwaju’s office, identified themselves and requested for an advance copy of the impending lecture.

How nice would it have been to give you a copy but the script is still being corrected. Innocently, he led them to the typing pool, called out the typist and asked how far. The typist replied she was just half way, a response the security operatives were hearing. Asiwaju added, again truthfully, how unsure if what was being typed was what would be delivered because such texts are hardly completed till the last moment as stuff are either being added or taken off to the last moment. He offered them invitation to the Lecture, assuring them of a copy then. According to Asiwaju, they looked at each other, thought about that and left. Meanwhile, it was still all quiet from the VC. He hadn’t mentioned anything about some 4 – eyed visitors curious about the substance of a lecture yet to come. He must have obviously thought it was one of the irritations of the Buhari administration which wasn’t worth bothering about.

The hall was jam packed on the D-Day, including the gallery. According to Asiwaju, when they watched the video of the Inaugural Lecture, they found there were NSO men, Army, Navy and Airforce officers in the audience. It had been a big event and Asiwaju was satisfied with himself. He had spoken about how the border closure had affected border populations, border communities, the embassies of countries around Nigeria, about what is to be done, new instruments, national, regional and continental options and so on. But, as he looked around and into the crowd, he sighted his previous visitors, signaling them to wait and let him finish the photo sessions. Thereafter, he called the Faculty Officer, asked him to photocopy the text and oblige the two gentlemen go away with the original copy.

However, a different set of visitors turned up on December 14th, 1984, two days after the Lecture. This time, they were two Other Ranks from the Army, not NSO again. They asked if they were in the office of Prof Asiwaju. They were told they were. They then declared they were from Dodan Barracks and they had come with an invitation to him to have a chat with the Head of State. Asiwaju’s office was still brimming with colleagues coming to congratulate him. One by one, they started leaving upon hearing the message.

Asiwaju then asked if he could come in his car. The answer was yes. Could he pass through his house? Again, the answer was yes. At home, the Prof said to Madam Victoria: I am going for a chat with the Head of State. Madam Victoria Asiwaju instantly read alarm into it and said they were going together. It was Prof’s job to convince her to stop crying, stay back and pray and worry less. She escorted him to where the military messengers parked their 404 and off they went towards Southwest Ikoyi.

It was when the first double iron-gate opened automatically at the site of the ‘convoy’ that Prof’s discomfort became most evident. The second gate, it was the same. He packed his car on their arrival in the office and they asked him to follow them. Then they arrived in the ante-room of the person he was to see. It was the office of the person’s Military Assistant. And the Military Assistant happened to be someone he more than knew. Lt Col Dotun Gbadebo was the Military Assistant, two years behind Asiwaju in History Department at Ibadan University and the current Alake of Egbaland. They even shared the same floor in Tedder Hall in the university.

By now, Prof’s temperature should be down from the anxiety boiling point but the military have their own codes and protocol. So, the sight of Gbadebo there may mean nothing if Gbadebo’s senior commands his detention. The main problem was the suspense about who he had actually been invited to see. Gbadebo told him it was the Office of the Chief of Staff Supreme Headquarters and he had informed him and is waiting for when to usher him in. He went ahead to congratulate him for the lecture, pointing out how it has been seminar upon seminars and all manners of discussion sessions for them in Dodan Barracks since the lecture. He further told Prof Asiwaju how sure he was that they were going to send for him and asked if he wanted beer or coffee. Prof was still not in the mood for any of the two. Idiagbon was more dreaded than Buhari at the time. and he was right in the lion’s den and they were asking him to drink beer or take coffee as if he was in the staff club. No, let him wait and enter and receive his sentence before he knew what to do.

By now, Prof’s temperature should be down from the anxiety boiling point but the military have their own codes and protocol. So, the sight of Gbadebo there may mean nothing if Gbadebo’s senior commands his detention. The main problem was the suspense about who he had actually been invited to see. Gbadebo told him it was the Office of the Chief of Staff Supreme Headquarters and he had informed him and is waiting for when to usher him in. He went ahead to congratulate him for the lecture, pointing out how it has been seminar upon seminars and all manners of discussion sessions for them in Dodan Barracks since the lecture. He further told Prof Asiwaju how sure he was that they were going to send for him and asked if he wanted beer or coffee. Prof was still not in the mood for any of the two. Idiagbon was more dreaded than Buhari at the time. and he was right in the lion’s den and they were asking him to drink beer or take coffee as if he was in the staff club. No, let him wait and enter and receive his sentence before he knew what to do.

Then Idiagbon gave him the shock of his life by coming out of the office smiling broadly, bald headed and well kept. Nothing of the media image of the stern, unsmiling enforcer. He asked himself what could be going on! Please, welcome, Prof! Please, sit down and all the courtesies coming from Idiagbon were too much for a Prof who was still ruffled. Then Idiagbon started to talk, drawing the curtain at a point to show him the diplomatic event going on in the Head of State’s office and the reason Asiwaju was meeting him (Idiagbon) when it was Buhari he was actually to have met. Asiwaju was not meeting Buhari because it was after they had decided to invite him that they discovered the diplomatic event was today. Prof could still recall Idiagbon talking: “We analysed your lecture line by line, paragraph by paragraph. We are convinced we do not know the structure we closed. We agree with you it has brought harm to people and even to government policies”. At a point, Idiagbon was saying if there were up to five academics like him in the country, Nigeria would be a better society. But Idiagbon had a question. “While we were going through the concluding section, we noted where you said that if you had the resources, you would have organised a better research. What is there to be further researched. It was the Head of State who said we must see you before we could say there is no further research to carry out”.

It was now Prof’s time to talk. When he found his voice, he said if he had the resources, he would carry out a detailed ethnographic survey Nigerian boundaries to deepen the human, cultural and other features enveloping the boundaries on either side.

Idiagbon took over again to deliver the message of the General Buhari to Asiwaju. Since the Head of State could not see you, he has preliminarily approved the sum of Five Million Naira for the possible kind of projects indicated. But the sum was not going to be domiciled in UNILAG. It was going to be domiciled in NIPSS, Kuru where there is also a plan to open a broader researcher.

This was greeted with a sigh from Prof, compelling Idiagbon to ask why. Prof explained how he had never stepped out of the UNILAG environment, a situation a NIPSS engagement would challenge. Secondly, how does he inform UNILAG of this development.

Idiagbon responded to all two worries. The NIPSS assignment wasn’t going to separate him from his family or from UNILAG. As for how he informs UNILAG of the funding that will be domiciled elsewhere, he was told not to worry about that. Government would handle that. Did he have any message for the Head of State? Prof asked the Chief of Staff to give the Head of State his warm regards. Ok, see you later. Dotun, see him to his car.

It was an unnecessary instruction. Prof was already out and close to his car. All Dotun’s entreaties of “Prof, wait na” didn’t strike. He looked back as each of the iron gates closed behind him until he was back with Madam Victoria in a few minutes thereafter. And then to the campus he went to dismiss any stories or speculations about what might have befallen him.

The Buhari/Idiagbon regime had branded campuses as hotbeds of subversive elements, banned seminars and even the most innocuous campus publications, declared hostility to undue radicalism, clamped too many people into detention. For a normal academic just going about his subject matter exploration, being clamped into detention for his views at an Inaugural Lecture was not the sort of experience to look forward to. An invitation from the Head of State in such a circumstance was bound to be terrifying. Typical of everything else in Prof Asiwaju, this turning point came from nowhere as it were. The Inaugural Lecture didn’t just inaugurate border studies, it launched him into border policy domain. It was the conversation between Idiagbon and Asiwaju that is today Nigeria’s National Boundaries Commission. Asiwaju has unfolded from the NIPSS project to working very closely with the late Brigadier-General John Shagaya when he was Minister for Internal Affairs under the Babangida regime down to working with Alfa Konare, fellow Historian and former President of Mali who became the pioneer Chairman of the African Commission (AU) and dragged Asiwaju along, amongst others.

With this behind, Prof Asiwaju is thus absolutely entitled to call the evening of December 12th, 2024 a special evening. The 40th anniversary of the Inaugural Lecture that brought him all these experiences cannot be otherwise.