It is a few hours to the start of the drama on August 1st, 2024. The expectation that Nigeria’s President Tinubu will make a major concession to the build-up against the regime before mid-night has evaporated. That must suggest to observers that the president has worked out a magic formula for undercutting what must be his most complicated personal and leadership nightmare ever – the material and symbolic vote of no confidence on him that a mass protest implies. Something of that nature seems so for those decoding the more defining rhetoric of government officials.

Kayode Egbetokun, the Inspector-General of Police, is the first on their list. His intelligence has told him that the protesters have been imported although the Customs Service, the DSS and the Immigration Services have not told the nation about influx of mercenaries recently. So, how did the IGP know that someone has imported mercenaries to serve as protesters?

Senator George Akume, the Secretary to the Government of the Federation put up a spectacular PR stunt on July 31st, 2024 that he has not been known for. He told the world that the president has no reservations against popular protests as a requirement for democracy except that they could foresee the invasion of the protests by bandits, insurgents and other criminals”. His words: “The government is wary of the dangers associated with protests that are vulnerable to being hijacked by bandits, insurgents and other criminals. Rather, we request that dialogue should be advanced and we remain open to such”.

Senator George Akume, the Secretary to the Government of the Federation put up a spectacular PR stunt on July 31st, 2024 that he has not been known for. He told the world that the president has no reservations against popular protests as a requirement for democracy except that they could foresee the invasion of the protests by bandits, insurgents and other criminals”. His words: “The government is wary of the dangers associated with protests that are vulnerable to being hijacked by bandits, insurgents and other criminals. Rather, we request that dialogue should be advanced and we remain open to such”.

Obviously, the SGF did not reckon with the unintended consequence of his statement in that it rubbishes the great works that Bennet Igwe, the FCT Commissioner of Police has done in ridding the capital city of the categories Senator Akume worries about. Around January and March 2024, bandits and insurgents were entering even military facilities in Africa’s most elaborate capital city, carting away victims in broad day light. Shocking killings, banditry and distressful domestic violence still go on in Abuja as in and around the entire Nigeria but the frequency is not as in January to March. If the SGF is to be believed, no such achievement can be entered for FCT Compol and the NPF itself.

The totality of the IGP and SGF’s arguments points to a government response to the mass protest at work: there will be no use of troops and the NPF might do no more than ‘protecting’ protesters. But protesters will be dispersed by “mercenaries”; “bandits”; “insurgents” and “other criminals” as prophesised by the IGP and the SGF.

Why might intellectuals of state craft and technocrats in power think along this pathway? Critics say only Carl Jung might be able to answer the question although it suggests that they still haven’t understood the nature of post-Cold War civil society in general and the Nigerian civil society in particular.

What is not in debate is that the typical civil society has never been the image of it envisaged by the grandmaster of its theorisation – Antonio Gramsci (as amended) as it is today. Even as wholly and amorphous as what is left of the civil society in Nigeria today, it is still a unique civil society in several regards. First is the extent of its assemblage character vis-a-vis the intellectual and cultural leadership for a test of strength with a regime that just doesn’t look empirically and ideologically prepared for such a test of strength. The second is its Leftist or socialist character, meaning it is not what the government of the day might easily defeat on matters of tactics.

What is not in debate is that the typical civil society has never been the image of it envisaged by the grandmaster of its theorisation – Antonio Gramsci (as amended) as it is today. Even as wholly and amorphous as what is left of the civil society in Nigeria today, it is still a unique civil society in several regards. First is the extent of its assemblage character vis-a-vis the intellectual and cultural leadership for a test of strength with a regime that just doesn’t look empirically and ideologically prepared for such a test of strength. The second is its Leftist or socialist character, meaning it is not what the government of the day might easily defeat on matters of tactics.

There is a third advantage which though not unique to it have its Nigerian applicability in key areas. One, the assemblage character referred to above functions in accordance with the logic of Gramsci’s ‘historic block’ away from conventional Marxian essentialism of the working class. Can a Tinubu regime defeat such an assemblage – unemployed youth, urban poor, frustrated working elements reduced to conditions unworthy of their locale, transitional elements such as students and corpers and even middle class elements forced to abandon their cars and ride ‘okada’ all over the place.

Two, there is another Gramscian metric – a “collective will”. Everyone has seen this in the bravery of some youth being slapped by some policemen in one of the viral video but who refused to retract their commitment to mass protest. Reports from even some of the rural states where it was assumed there will be no mass actions are belying such assumptions

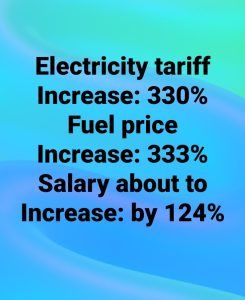

Three, the mass protest is anchored on discourses rather than rigid ideological claims of good and bad. The protesters have been mobilised by the policy trajectory of the government to frame the protest in terms of survival, suffering, hardships which they relate to bad governance and for which they find the president the symbol. Such protests can be difficult to suppress because they have departed from rigid ideological fixations to fluid flow of meaning that can absorb new responses to them contingently.

Three, the mass protest is anchored on discourses rather than rigid ideological claims of good and bad. The protesters have been mobilised by the policy trajectory of the government to frame the protest in terms of survival, suffering, hardships which they relate to bad governance and for which they find the president the symbol. Such protests can be difficult to suppress because they have departed from rigid ideological fixations to fluid flow of meaning that can absorb new responses to them contingently.

Four, the fall out of the aforementioned factors have resolved some of the difficulties or problems of classical Marxism that put on the ways of popular assertion especially in non-industrial societies such as Nigeria. There is no longer the burden of a correct party line embodied only by the Politburo members and an all-powerful Communist Party secretary. What Gramsci called ‘historic blocks’ have inherent advantage of chains of equivalence which can already be observed in the articulation of the current protest for those observing carefully.

Marxism or some variant of it still guide much of radical politics/mass protests in non-industrial societies which is why (radical) populism is so powerful in Latin America, for example. But even then, a constructivist rather than structuralist reasoning define much of the praxis, with the advantage that a Jacobinist seizure of the state is de-emphasised in favour of deconstructing the state. That is evident in the impending mass protest in its engagement with the regime’s fuel subsidy practice. Questions such as why the refineries are not working; why are levies and taxes rising while salaries are still no more than starvation wages and why affluence and wastage define governance while the people are endlessly asked to make sacrifices speak to this claim. Those who argue that the ‘pregnancy of the silence’ in government on these leading question shows that protesters have already won a moral victory have a point. The government, they assert, is silent because it has no convincing things to offer on the questions.

But does it mean protesters will have a field day all over Nigeria, thereby translating their existing moral victory to empirical victory over the government between August 1st to 10th, 2024? Well, a mass protest in Nigeria can never be a local but a global event and in which the key players become instant actors on a global stage. Contexts can be very important in all social situations..