By Adagbo Onoja

Dr. Yusuf Bangura, the ex-Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria Political Scientist, keeps a critical eye on the arts and posts a lot of arty stuff. Yesterday, one of his posts is an announcement of the folding up of the British edition of the US based publication, Reader’s Digest. The announcement, dated May 3rd, 2024 was instructively titled “End of an Era: Thank You for the Memories.” It is the end of an era, indeed, although it is not immediately clear if the American edition is shutting down too or has done so much earlier.

Reader’s Digest was another source of ‘entertainment’ for the Bangura generation across Africa. An alternative name for them is Emmanuel Ayandele’s notion of the educated elite to whom independence opened opportunities that were previously not there. And this was with particular reference to the world of the media. Reader’s Digest was part of the storehouses that came with this. It was a useful source in the broad realms of leisure, short stories, travels, adventure, puzzles and lifestyle. As Bangura put it through to Intervention, they as young minds at the time were simply interested in the puzzles, quizzes, and stories as good fiction, not whatever agenda of the creators or the outcome of its reportorial frame of reference. Readers in that generation were not alone as even graduate students in sub-disciplines such as International Relations, Global Governance, History and Geopolitics hardly took it beyond the entertainment sense of the stuff.

Reader’s Digest was another source of ‘entertainment’ for the Bangura generation across Africa. An alternative name for them is Emmanuel Ayandele’s notion of the educated elite to whom independence opened opportunities that were previously not there. And this was with particular reference to the world of the media. Reader’s Digest was part of the storehouses that came with this. It was a useful source in the broad realms of leisure, short stories, travels, adventure, puzzles and lifestyle. As Bangura put it through to Intervention, they as young minds at the time were simply interested in the puzzles, quizzes, and stories as good fiction, not whatever agenda of the creators or the outcome of its reportorial frame of reference. Readers in that generation were not alone as even graduate students in sub-disciplines such as International Relations, Global Governance, History and Geopolitics hardly took it beyond the entertainment sense of the stuff.

If I use myself as an example, it was a shocker for me to find an essay/book (she has both of each) such as Joanne Sharp’s Condensing the Cold War: Reader’s Digest and American Identity on the reading list of my course unit ‘Theories of Globalisation’ in the MSc in Global Governance programme at the University College London as late as 2014. Yet, the book which started as a term paper in popular geopolitics sits pretty with other essays that have been definitive of the field in contemporary and not so contemporary Western world. Among these would include Halford Mackinder’s “Geographical Pivot of History” delivered at Oxford in 1904; Robert Cox’s 1981 essay, “Social Forces, States and World Order” Carol Cohn’s “Sex and Death in the Rational World of Defense Intellectuals” and Stephen Walt’s “The Renaissance of Security Studies”. Of course, this list could differ but not too remarkably if compiled by someone else. The point is that there is something new, revealing or provocative in each of these publications even when some of them are ideologically disagreeable.

What Sharp’s study of Reader’s Digest brought out most clearly is that, as a popular culture site, it was a powerful instrument for manufacturing consent or hegemony if you like. Prof Sharp who has since moved to the University of St Andrews from the University of Glasgow, all in Scotland, showed how Reader’s Digest was such a powerful ideological platform for constructing and constituting American identity through the meta-geographical narrative of America in terms of the country with a destiny and the magazine as guardian of the materialisation of that destiny. In time, it became the guardian on a thoroughly global scale: 16 million readers a month within the United States and over 27 million copies read around the world each month in seventeen languages. With this, Sharp could write in the Introduction to the book how “The Digest is a cultural production that cannot be ignored given the wide reception of its message in America and across the world; it is an important and trusted source of information, advice, and knowledge for many people” (P. xiv).

This background explains its representation of the US as the very opposite of the USSR throughout the Cold War. It did this through the angles it took in framing its features, the punditry and the pundits and the general sense or direction of the world that a typical reader got. Sharp’s technique for engaging the content of Reader’s Digest is deconstruction. That comes with deficiencies and controversies associated with the technique but the overarching inference is intact. It does because the question is how did it happen that Americans who had little or no encounter with other sources of information at the time were and are so terrified of communism? They must be under the influence of some one-dimensional sources of information about communism. That source of information is what is now known in popular geopolitics as Tabloid geopolitics, a virulent instrumentalization of fear, threat, danger and uncertainty in daily life. It is the kind of stuff Bill O’Reilly stands for in contemporary America – red herring, hysteria and all other elements of ‘banal nationalism’. This is not to suggest or connect Reader’s Digest to that tradition.

Meaning is what is unsaid!

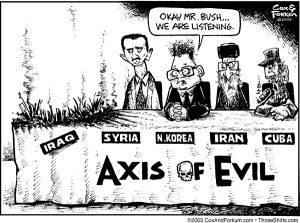

The other achievement of her work is rupturing the excessive stress on high politics. There is no high politics – diplomacy, war, trade negotiations – that preceded or could make sense outside of discourse. That is what we saw with the narrative of paganism as a justification for colonialism; in the narrative of 9/11 as a declaration of war even when the actors were not state agents; in the narrative of weapons of mass destruction ahead of the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and in the stalled narrative of ‘axis of evil’ against Iran, Cuba, North Korea. So, there is no China Wall between high and low politics. One delineates the boundaries for the other. That is why the shooting wars are preceded by quick dash of presidents and prime ministers, long consultative phone calls, press statements, all preparing the ground for action. It is narratives that define wars, trade relations and all that.

Interestingly, this is an analysis supported by all analytical tendencies in political analysis. There is a sense in which Barry Buzan may be guilty of exaggeration but there is also something serious in him saying that “there are traditions within realism that are receptive to the idea of language as power and discourse as a major key to politics”. I am quoting from his interesting book chapter “The timeless wisdom of realism?”. When one thinks through the big names in the discipline, he may need no more than one or two qualifiers to go scot-free with this statement, not with E. H Carr, Kenneth Waltz, Ole Waever, the group in Marxist geopolitics and the entire constructivist family in International Relations comfortably with him.

The last merit of Sharp’s work is the interesting phenomenon whereby nearly all the articulations of Empire in the post-Cold War were first published in a popular culture platform before it was advanced elsewhere. This has been the case whether we are talking of the highly popular but Otherising frame of West Africa as a threat to international security in Robert Kaplan’s The Coming Anarchy; Michael Barnett‘s manual for post-Cold War American practice of Empire titled The Pentagon’s New Map, Samuel Huntington’s hegemonic cartography which he called The Clash of Civilisations? which, arguably, prepared the grounds for the global war on terror that sought to overwrite sovereignty. And even Edward Said’s caustic response to Huntington titled The Clash of Ignorance. And, of course, ‘Africa rising’ which came through Time magazine long before The Economist intervened.

If nearly all the narratives supportive of Empire and domination are manifestoes and manuals that found their way out through popular culture, then why should we worry when a platform such as the Reader’s Digest closes shop? The answer is best illustrated by the stalemate over ‘CNN Effect’.

The puzzle around ‘CNN Effect’ which arose after CNN’s round-the-clock coverage of the First Gulf War and other sites of global misery lies in whether the instant images and narratives of such grave events stampede the great powers to act or not. If it does, then it means media reports are inherently influential, almost without any intervening variables. If the contrary is the case, then ‘CNN Effect’ is nothing more than a fad. Each side had its own protagonists and the stalemate took some time, with a lot of publishing on both sides.

The power relations are already forming from the rhetoric, strategic stories and clashing ‘regimes of truth even when much of Africa is still searching the dictionary for the meaning of ‘Africa rising!

US based Irish scholar, Gerald O’Tuathail and his colleague, Prof Mathew Luke offered what appears to have settled the quarrel. They did so by saying that, depending on the interpretation of a report in a newspaper, television or radio or online, it could act in the service of hegemony just as it could equally serve a counter-hegemonic purpose. In other words, images from a particular warfront or negotiation or ethnic violence or whatever could so incense popular sentiments as to render a hegemonic script impossible. Another set of pictures or images could actually help a hegemon to push ahead. It depends on whom is moblised by any set of images. The images do not contain their own meaning in themselves. They must be interpreted and re-articulated to produce any outcomes.

As such, no critical perspective, be it postmodernism, poststructuralism or deconstructionism has ever declared that language alone can produce consequences. There is a sense in which Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, the pioneers of the most influential of the several approaches in discourse theory anticipated this and responded to it in 1985 by saying that nobody ever said so. What they said is the rather completely different point that no object has any meaning outside of discourse and that the fact that all the currents in 20th century philosophy – structuralism, phenomenology and poststructuralism have one feature in common – discourse – should make us think. This is where Buzan’s earlier claim already referred to makes even more sense.

What it all means is that one can confidently restate an earlier claim of emancipatory potential for popular culture in Africa. This is made even more potent by informationalised capitalism if we follow O’Tuathail argument on the “ÇNN Effect”. The ideas of the ruling class might still be the ruling ideas as Marx argued but Laclau and Mouffe have so radicalized Gramsci on hegemony that we can also confidently assert that it is only in certain themes and places that the ideas of the ruling class can be the ruling ideas. This has to be so because hegemony is not something which can be secured with law or military force. It is too elusive to be controllable, meaning that counter-hegemonic construction and constitution of reality from below is not only possible but relatively easier, courtesy of popular culture in the age of informationalised capitalism and the ubiquitous social media.

What more evidence do we need if, for now, the possibility of military base for two great powers – the US and France – in one of Africa’s most strategic countries has been disrupted by a mere open letter to the president and legislative leaders of Nigeria by just seven persons? That is the classic discourse – power nexus in action. It was not just the language of the open letter but the subject positions it propped up in the standpoint politics of MURIC, PRP and others at the background which neither the US/France nor the Nigerian Government are in a position to take – on now. With that outcome from the open letter , it is safe to say there can be no reality without discourse.

Of course, a brilliant government can reverse the misfortune because hegemony cannot be consolidated but to reverse it requires an articulatory practice that neither the Nigerian Government nor even the great powers can muster in the current balance of discursive warfare. In the long run, a lot would have shifted too.

The challenge of discourse and popular culture for degraded players in world politics is therefore the imperative of deeper mastery of the politics of signification instead of the current static infatuation with structuralist reasoning in much of Africa. It is only with such that a platform such as the Reader’s Digest can also advance radical causes through the logic of hegemony or counter-hegemonic narrativisation, particularly its construction and sedimentation. That is why it matters when any newspaper, television, university, NGO and any popular culture platform dies. Or when a country such as Nigeria just cannot get its acts together on a power resource as the recent innovations in the realm of home movies, musical talents and the culture industry, broadly!