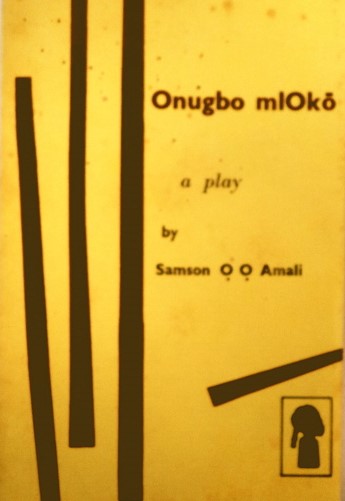

My Facebook culture is still of a disordered nature and I could have missed Prof Moses Ochonu’s approving comments on the piece “The Araba Hip-hop of Idomaland As a Challenge for Okanga 1 of Idomaland” that Intervention published May 23, 2023. Ochonu’s intervention is strategic in more than one sense. He is intellectually, culturally and ideologically located to appreciate the inter-cosmological character of emergent global relations. Above all, he is in the institutional context to identify and oblige the sort of younger elements in Idomaland the opportunity for the kind of training that some scholars of Idoma identity got in the domain in question. The most notable name with which to illustrate this would be Professor Shamsudeen Amali who went on to write Onugbo Mla’Oko which is, unfortunately, all but forgotten now.

Anyway, Prof Ochonu’s Facebook reaction is reproduced belowL

“The risk there is there might be no PhD thesis on a Joe Akatu or Bongos Ikwue until someone comes from Scotland or Berlin to do one.”

These are the profound words I extracted from a piece written by my senior friend and brother, Adagbo Onoja, and published in Intervention, the online publication he edits.

Bongos Ikwue most Nigerians of a certain age know, but for those who don’t know, Joe Akatu was a pioneer, if not THE pioneer, Idoma folk singer and composer. As a child, I was mesmerized when a wealthy neighbour invited him to give a concert at his home.

What impressed me the most was his ability to see a situation, even a mundane one at his concert, and compose and perform a song about it right then.

Anyway, back to Onoja’s point and its larger ramifications.

How many of our scholars in the humanities and humanistic social sciences are studying the works and lives of these musical and artistic legends?

How many of our scholars in Nigeria have researched and published on Mamman Shata, Osita Osadebe, Orlando Owoh, Victor Uwaifo, Bala Miller, Salawa Abeni, Christy Essien, Dankwairo, Barmani Choge, Dan Maraya, etc?

They’re all looking for “viable topics” or their supervisors are telling them to look for such topics—whatever “viable topics” means.

Some of them even come to our inbox to ask us to suggest topics to them or to “help me with materials.” Meanwhile, while they’re looking for topics in Sokoto, these active and retired musical treasures are right there in their proverbial shokoto waiting and begging to be mined for “materials,” data, and insights.

When some of the more ambitious graduate students propose to research these “obscure” subjects, their supervisors advise them against it because as they say, “there are no materials,” which sometimes means “there are no existing works that you can replicate or even plagiarize, and I don’t believe enough in your intellectual ability to pioneer the study of Joe Akatu or Igbe or Peter Otulu.”

We then celebrate or complain when scholars from elsewhere come in to study these artistes’ body of work and are the first to extract and highlight the philosophical, moral, literary, and cultural insights of these vernacular musical productions.

We giddily consume these works or complain about how “foreigners” are the ones studying and publishing on our artistic heritage.