It may not be the allowed practice to take so long a quote as this from someone else’s work. Intervention is, however, sure The Washington Post will approve of this rare case of that. The portion from its Ishaan Tharoor edited Today’s Worldview newsletter of May 26th, 2022 is not just another featurised opinion but also a must read for students of Global Governance, from the title to the content:

This year’s gathering had been billed as a moment to reckon with history at a turning point. The world (and particularly the Davos set, who wield such influence over it) were to face up to a cascading series of crises — the war in Ukraine, the turbulent tail-end of the pandemic and surging food and fuel prices that are destabilizing societies and governments in every continent.

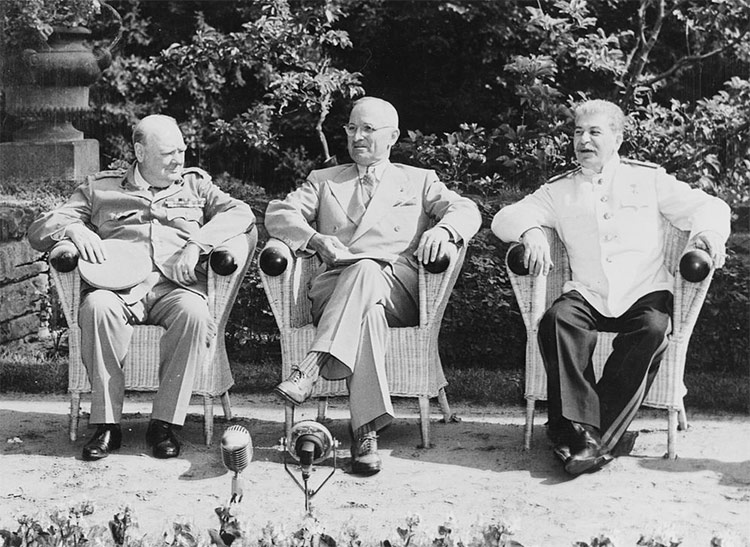

A pix from the last G7 meeting

Instead, the discussions exposed big gaps between participants. Analysts and policymakers from regions outside the West questioned for whom history was actually turning. Some rolled their eyes at the emotional European reaction to events in Ukraine, and pointed to double standards in their neglect of ruinous conflicts elsewhere and disdain for earlier waves of refugees.

“For us, superpower rivalry has always been at our doorstep — it was Soviet Union and the U.S., now it’s China at the U.S.,” Malaysian Health Minister Khairy Jamaluddin told me. “So to us, (the Ukraine war) is really just a blip, not really a turning point.”

Jamaluddin lamented that “the ‘color of your skin’ argument” still seemed relevant. Now that violence and state terror “affects somebody who looks like you” — that is, a White Westerner — “suddenly, there’s this moral outrage from Washington to Davos,” he said.

The moral outrage comes with a deepening of fault lines in global politics. Alexander Stubb, former prime minister of Finland and director of the School of Transnational Governance at the European University Institute, described the moment to me as “a kind of reverse 1989,” where rather than an Iron Curtain coming tumbling down, new ramparts between rival powers are rising up.

“We are seeing the hardening of geopolitical competition along ideological lines,” said Lynn Kuok, a Singapore-based senior fellow for the International Institute for Strategic Studies. No matter the pearl-clutching in Davos over Russia’s violations of international law, “Asia has already seen its own erosion of the rules-based order” in the form of various coercive measures taken by China in recent years, Kuok added.

But countries in Southeast Asia remain “uncomfortable,” she said, with the “democracy vs. autocracy” frame that many in the United States and Europe seem to want to place around contemporary challenges.

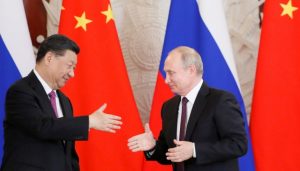

The nucleus of a new Warsaw Pact?

“There’s a Manichaean, Occidental urge to see the world in binaries,” Samir Saran, president of the Observer Research Foundation, an influential New Delhi think tank, told me. “We work in shades of gray.”

The absence of prominent Russian and Chinese voices this week in Davos — an unusual development for a forum that prides itself on convening diverse participants — itself spoke volumes.

“What do liberal values really mean?” said Hina Rabbani Khar, Pakistani minister of state for foreign affairs. “They mean room for other opinions to coexist.” Khar added that she saw the prevailing moment as a “really dangerous” one, with antipathies mounting and dialogue fading.

That’s all the more unfortunate at a time when the main “structures in global governance” are failing, as Adam Tooze, economic historian at Columbia University and Davos regular, put it to me.

The war in Ukraine has undermined the ability of the Group of 20 nations — a bloc in which the United States, major European economies and Russia all belong — to be an effective platform for global cooperation at a time of looming economic crisis. Ongoing trade wars and rising protectionism have hollowed out the World Trade Organization’s efficacy, while many countries in the Global South remain furious with the West over its hoarding of coronavirus vaccine doses during the pandemic and its slowness in distributing jabs to the rest of the world.

“The sense of anxiety that arises from these converging crises,” Tooze argued, has in part to do with the reality that “the organizations we do have are not just inadequate to the task, but there’s actually warlike antagonism” within them.

To be fair, many Western politicians attending the events in Davos seemed aware of the challenges ahead. “We really do a disservice to our potential role in the world by projecting a lack of humility about the limitations to our role in the world,” Sen. Christopher A. Coons (D-Del.), a leading member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, told Today’s WorldView.

Coons pointed to the importance of recognizing differing perspectives from democracies in Asia and Africa, considering the pressures of mounting food prices around the world and the ongoing toll of the pandemic. Western unity in support of Ukraine marks “an important moment,” he said, “but we have to see it in context.”

The question facing policymakers in Davos and elsewhere, Germany’s Scholz suggested, is a tough one: “How can we create an order in which very different centers of power can interact in the interests of everyone?”

The answer, the German chancellor said, has no precedent in history.