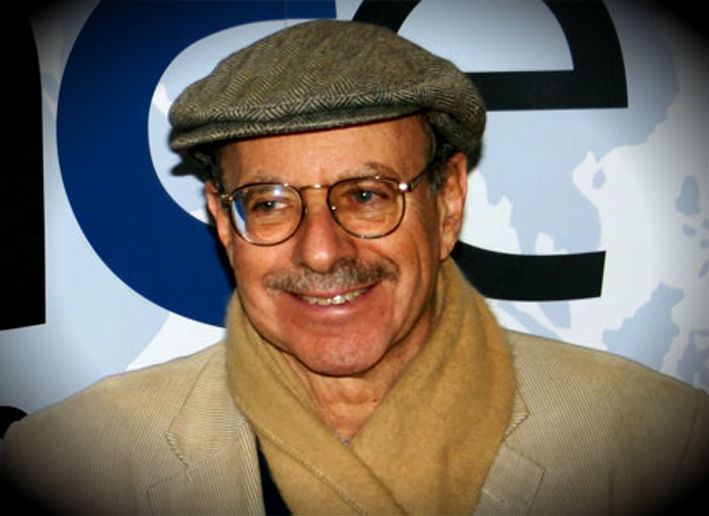

Time and tide would seem to have taken the sting out of this contention by US based radical Sociologist, Professor James Petras. The blast from the scholar – activist extraordinaire is published here only as Intervention’s flashback ahead of his 85th birthday next January. It is extracted from his April 1989 essay titled “The Metamorphosis of Latin America’s Intellectuals”. This portion reproduced below made waves in the mid-1990s across Africa when it was massively circulated. So much has changed since then but certain things said in certain ways manage to escape the space and time constraint by remaining simply memorable!

“An apocryphal episode occurred during my visit to Chile. A director of a research center invited his mother from the provinces to visit him in Santiago. He drove to the airport in his new Peugeot to pick her up. “Where did you get this beautiful car?” she exclaimed as she observed all the gadgets on the dashboard. “The Institute financed it. I need it for my research to overthrow the dictatorship,” he answered. When they arrived at his suburban home, the mother gazed with wonder. “Where did you get this beautiful house?”

“The Institute financed it. I need it for my research to overthrow the dictatorship.” They entered the dining room, where dinner was waiting: a table covered with shellfish, fowl, salads, fruit, and fine wine. Eating heartily she asked, “Where did you get such an elaborate meal?” “The Institute finances it. I need it for my research to overthrow the dictatorship.” At this point, his mother plucked his ear and whispered, “Be careful they don’t overthrow the dictatorship and you lose everything.”

The two paragraphs above is what was circulated then. The background to the two paragraphs is what Prof Petras gives as follows as far as the 1989 essay is concerned as the reader encounters a slightly different version of it in his other texts, especially in his 1990 book with Morris Morley titled US Hegemony Under Siege: Class, Politics and Development in Latin America, published in London by Verso.

:The transformation of the Latin American intellectuals center on their incorporation as research functionaries into institutes dependent on external funding. Their work requires them to provide information that their benefactors would not otherwise possess and, even more important, to circulate and implant the ideas and concepts acceptable to their benefactors as the dominant ideology within the political class.

THE CHANGING INTELLECTUAL PIVOT

In the past, Latin America possessed – in the best of cases – what Gramsci called “organic intellectuals,” writers, journalists, and political economists linked directly to political and social struggles against imperialism and capitalism. They were integral parts of trade unions, student movements, or revolutionary parties. Che Guevara, Camilo Torres in Colombia, Luis de la Puente in Peru, Miguel Enriquez in Chile, Roberto Santucho in Argentina and Julio Castro in Uruguay were a few of the hundreds if not thousands of intellectuals who integrated their intellectual work with the social struggles of their countries.

The consequential organic intellectuals established the norms of behavior for the rest of the intellectual class. For thousands of other intellectuals the political and personal example of the organic intellectuals served as a measuring rod which they approximated to a greater or lesser degree. There was a continual “internal” struggle between professional opportunism and political commitments, as Latin American intellectuals strove to make existential choices. This struggle no longer exists – it has long been resolved and forgotten among the new breed of research-institute- oriented intellectuals. The problem now is how best to secure the largest sum of money from the most accessible outside funding agency. Today the institutionalized intellectuals are, in a Foucaultian sense, prisoners of their own narrow professional desires (see Foucault, 1979). Their links with the external foundations, international bureaucracies, and research centers dominate a vacuous and vicarious internal political life. In the past the organic intellectuals struggled with a self-sustaining, self-financing intellectual existence. They lived and suffered the economic cycles of their countries.

Today the institutional intellectuals live and work in an externally dependent world, sheltered by payments in hard currency and income derived independently of local economic circumstances. The deep internal horizontal linkages between the organic intellectual and civil society contrast with the vertical linkages between the institutional intellectual and the external funding agencies and, with the advent of civilian regimes, with the local state and regimes. The dictatorships indirectly created a new class of “internationally” oriented intellectuals, ostensible critics of the neoliberal economic model, but just as deeply embedded in dependent relations with overseas networks as their adversaries among the export-oriented and financial elites. This new class has a life- and work-style that contrasts sharply with preceding generations of organic intellectuals.