It is judgment hour for South African president, Cyril Ramaphosa. He is clocking three years in power and his country’s media is not awarding clear pass marks. Certainly not in this piece from the Daily Maverick which wrote this rider to a major assessment of Ramaphosa: On Thursday, President Cyril Ramaphosa steps up to the podium to deliver his fifth State of the Nation Address. On 4 March, he will have been in office for 1,111 days. In these three years, what has he achieved?

The author

By Ferial Haffajee

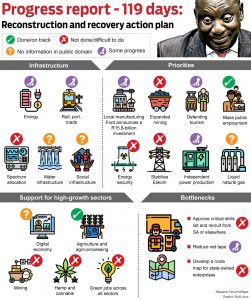

Since 2018, Daily Maverick has tracked President Cyril Ramaphosa’s progress on 24 key themes he set out in his first State of the Nation Address. And more than 1,000 days later, the graphic shows that he has not made significant progress.

As a former business leader, Ramaphosa staked his game on economic transformation and job creation, repeatedly promising to deal with inefficient energy supply as well as bottlenecks like the stalled Mining Charter and the failure to auction spectrum on which data can travel more quickly and more cheaply.

Ramaphosa has failed to oversee the fix on Eskom, which is still load shedding, adding to the mayhem that Covid-19 has wrought on the economy. He also promised a better social wage (good transport, housing close to work, etc) and that no person would go to bed hungry. But with a desultory social cluster in his Cabinet, he has not achieved these vital goals.

According to crime statistics, South Africans are more unsafe than ever before in democratic South Africa, making a mockery of the president’s pledge that violent crime would be halved in his term. Where Ramaphosa does deserve kudos is in the way that he has tackled gender-based violence as a war on women. But he can only claim victory when the numbers come down, and there isn’t evidence of that yet.

Most leaders, other than perhaps New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern, have suffered under the weight of Covid-19, which has caused health, economic and social crises in countries in almost equal measure. Ramaphosa is no different. His plans for a National Health Insurance, and to double the number of tourists landing in SA by, for example, establishing a “world-class e-visa regime” have been stalled by the virus. It’s a moot point to consider whether he would have been able to pull South Africa from its junk investment-grade rating if Covid had not made landfall here in March 2020. You can’t say.

Our graphic shows that Ramaphosa has been good at ensuring that South Africa’s response to the coronavirus and the Covid-19 pandemic has been measured. It has been scientist-led (unlike those of, for example, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro or the UK’s Boris Johnson), and the quick action to put the country into lockdown was the right thing to do. There has been some social relief, but probably not enough.

Our graphic shows that Ramaphosa has been good at ensuring that South Africa’s response to the coronavirus and the Covid-19 pandemic has been measured. It has been scientist-led (unlike those of, for example, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro or the UK’s Boris Johnson), and the quick action to put the country into lockdown was the right thing to do. There has been some social relief, but probably not enough.

The hundreds of thousands of arrests by the police and defence force mean that South Africa suffered one of the most violent jackboot lockdowns. The other failure has been to adopt a more agile vaccine strategy. The reason for that is because the coffers were bare when South Africa needed to place early orders.

Ramaphosa’s first 100 days in office saw significant reform of institutions such as Eskom, Transnet, the SA Revenue Service, the National Treasury, the Public Investment Corporation, the Special Investigating Unit and the Hawks.

The criminal justice cluster is enjoying an Indian summer of prosecutions, with political bigwigs charged with corruption by an invigorated National Prosecuting Authority. But the reform effort has stalled at key points such as Eskom when measured at 1,111 days of the president being in office.

While the National Director of Public Prosecutions (NDPP), Shamila Batohi, is earning her spurs with regular charges against the most corrupt individuals of the State Capture era, she is far from putting anybody into orange overalls.

Is it possible Madiba’s spirit is not breathing down on his legatees?

Ramaphosa’s method is to secure buy-in and broad consensus before he moves on anything. It has worked for him in the past, and he still relies on the method. But with the political fightback against him gathering steam, he will face significant headwinds if he tries to run for a second term as ANC president. The party is due to have an elective conference in 2022 and a national general council later in 2021 – it’s not clear if both will proceed, but there is a growing lobby to ensure they do.

If so, Ramaphosa is going to have to walk over coals to stay in office. One way to do so is to show a record of doing what he says he will do, but our tracking shows he does not do so at a pace that could secure his place in the ANC and history.

The third graphic in our series takes the pulse of Ramaphosa’s Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Action Plan he launched in October 2020.

It is called an “action plan”, and there has been some progress, as indicated. Still, on the big-ticket items like energy security, expanded mining, stabilising Eskom and moving quickly on high-growth sectors, there is no tangible progress. After 119 days and with significant power, Ramaphosa should have more to show. He is likely to focus on his presidential employment stimulus, which has already secured 400,000 work opportunities for young people, but it’s a public works project.

And, while Ramaphosa has staked his success on a R1-trillion presidential infrastructure plan, so did his predecessor, Jacob Zuma. DM