By Adagbo Onoja

As a panelist on a recent CDD event, one came face to face with a totally surprising clamour for media reports that are not sensational but objective and balanced. This was not coming from very humble human beings but well heeled members of the society located in academia, diplomacy, activism and related social domains. I tried to clarify how illusory it is to expect sensation free, balanced and objective reporting but it didn’t seem that people could free themselves from collective self-imprisonment in things that are not worth such efforts. At the end of the day, there was a consensus between Dr. Chris Kwaja and I to repeat myself in writing and thus put something on the table for further engagement. I thank Dr. Kwaja for the consensus because, by that, he gives me an opportunity to hit back at all those who could not come to terms with my key contention that the media plays both escalatory and de-escalatory role when it reports conflict but not in the way that is popularly imagined. There is no such direct impact of media reporting without intervening variables or in which a media report produces or solely leads to a negative outcome. Instead of such relationship, what sensationalism and lack of objectivity do are themselves dependent on readers and the conflict context. It is for those two reasons that it is not so much in the media industry but even more in the larger society that the work to be done on the much talked about conflict sensitive reporting lies.

The first shocker about the excessive concern with lack of balance and objectivity is the question about where people got the idea at all that the media has anything much to offer in favour of peace. As a contested terrain, the media works for the power that controls it. Theorists of ‘the Sociology of the newsroom’ would argue that journalism or the media generally sympathises with the underdog but very few graduates of Mass Communication up to the early 1990s would have missed Jörg Becker’s essay, “Peace and Communication. The Empirical and Theoretical Relation Between Two Categories in Social Sciences”. There, it is very well demonstrated how the media works as an anti-thesis of peace because, according to Becker, the media is part and parcel of the structure of violence, hence the media’s inherent value bias for violence.

We can accuse Becker of structuralist reasoning but there is almost no successor to the structuralist legacy who has challenged Becker. To the contrary, the signature sentence in Prof James Der Derian’s masterpiece, Virtuous War, is generally believed to be where he said that those who control digital technology for bringing there here exercise what he calls a technological and representational form of deterrence and control. It is from that digital advantage that the audience became implicated in technology fetishism because technological visualisation has a way of desensitizing the human mind to violence in the context of a so-called ‘hygienic war’ in which violent deaths are, to a great extent, hidden from viewers. So, there is something a bit incomprehensible where people got the idea that the media can bring about peace if they follow a conflict sensitive reporting pathway. The media as a social institution is not located to be able to do that, thereby rendering the prospects of peaceful reporting a nullity, ab initio.

We can accuse Becker of structuralist reasoning but there is almost no successor to the structuralist legacy who has challenged Becker. To the contrary, the signature sentence in Prof James Der Derian’s masterpiece, Virtuous War, is generally believed to be where he said that those who control digital technology for bringing there here exercise what he calls a technological and representational form of deterrence and control. It is from that digital advantage that the audience became implicated in technology fetishism because technological visualisation has a way of desensitizing the human mind to violence in the context of a so-called ‘hygienic war’ in which violent deaths are, to a great extent, hidden from viewers. So, there is something a bit incomprehensible where people got the idea that the media can bring about peace if they follow a conflict sensitive reporting pathway. The media as a social institution is not located to be able to do that, thereby rendering the prospects of peaceful reporting a nullity, ab initio.

Johann Galtung, the veteran of Peace Research has provided a very useful 12-point critique of media coverage of violence worth extracting from: de-contextualization of violence; the dualisation of the number of parties in a conflict to two; the Manichean portrayal of one side as good and the demonization of the other as “evil”; the Armageddon sense of violence which sees it as inevitable while avoiding structural causes like poverty, government neglect and military or police repression; the confusion associated with focusing only on the battlefield or location of violent incidents without same focus on the forces and factors that influence the violence.

There is a second explanation for why it is absurd to expect objectivity and balance from media reporting, a process which is inherently about simultaneous inclusion and exclusion. That is another way of saying that the very act of reporting is inherently selective and subjective. Every journalist who deals with selecting events to cover and write a story on is involved in a very subjective process. Time, financial and human resources are so limited that very few media houses can afford to send a reporter to report on every newsworthy event that takes place in a town or city or village. It means that the stories every medium publishes either in its bulletin or news pages have been selected, meaning the exclusion of so many others. There are no objective reasons why any story will be publishable but not the other. Journalism teachers have come up with beautiful lies about the criteria by which newsworthiness or otherwise are decided. They are no such criteria. They are all ideological justifications for ditching one set of stories for another set. If this were not so, why is it the case that it is the very stories rejected by one newspaper on the basis of those criteria that are privileged and published by another set of newspaper(s), using the same criteria.

There is a third angle to look at the issue. It lies in the specificity of meaning. What a story means to a wife might not be what it means to her husband even as they sleep on a same bed. What a story means to a Christian may not be what it means to a Muslim. This specificity of meaning is why a media report of a conflict can result in a catastrophe. However, it is not a particular report in and of itself that is responsible for that but the interpretation of the story. Thus the Danish cartoon in far away Denmark was interpreted differently in Nigeria as to lead to violence in Maiduguri but no such thing in Lagos or even Kano. To an extent, therefore, it is subjectivity of the reader(s) that is more problematic than a story in itself.

There is a third angle to look at the issue. It lies in the specificity of meaning. What a story means to a wife might not be what it means to her husband even as they sleep on a same bed. What a story means to a Christian may not be what it means to a Muslim. This specificity of meaning is why a media report of a conflict can result in a catastrophe. However, it is not a particular report in and of itself that is responsible for that but the interpretation of the story. Thus the Danish cartoon in far away Denmark was interpreted differently in Nigeria as to lead to violence in Maiduguri but no such thing in Lagos or even Kano. To an extent, therefore, it is subjectivity of the reader(s) that is more problematic than a story in itself.

This is more so when a particular issue such as the last wave of herder-farmers conflict in Nigeria not only had a multiplicity of conflict parties but parties characterised by imbalance of power. In that conflict, there was the Federal Government of Nigeria as both a conflict party (because the president was, coincidentally, a Fulani and thus a suspect) as well as the ultimate conflict manager; specific governors; Miyetti Allah; MACBAN; security agencies; the civil society and lots more. In such situations, the set of conflict parties with smarter narratives do tend to carry the day because their own narrative tend to become commonsensical as to act as frame of reference for many of the actors. So, the Federal Government found itself outflanked in the battle of narratives even as it had overwhelming advantage in terms of repressive state institutions.

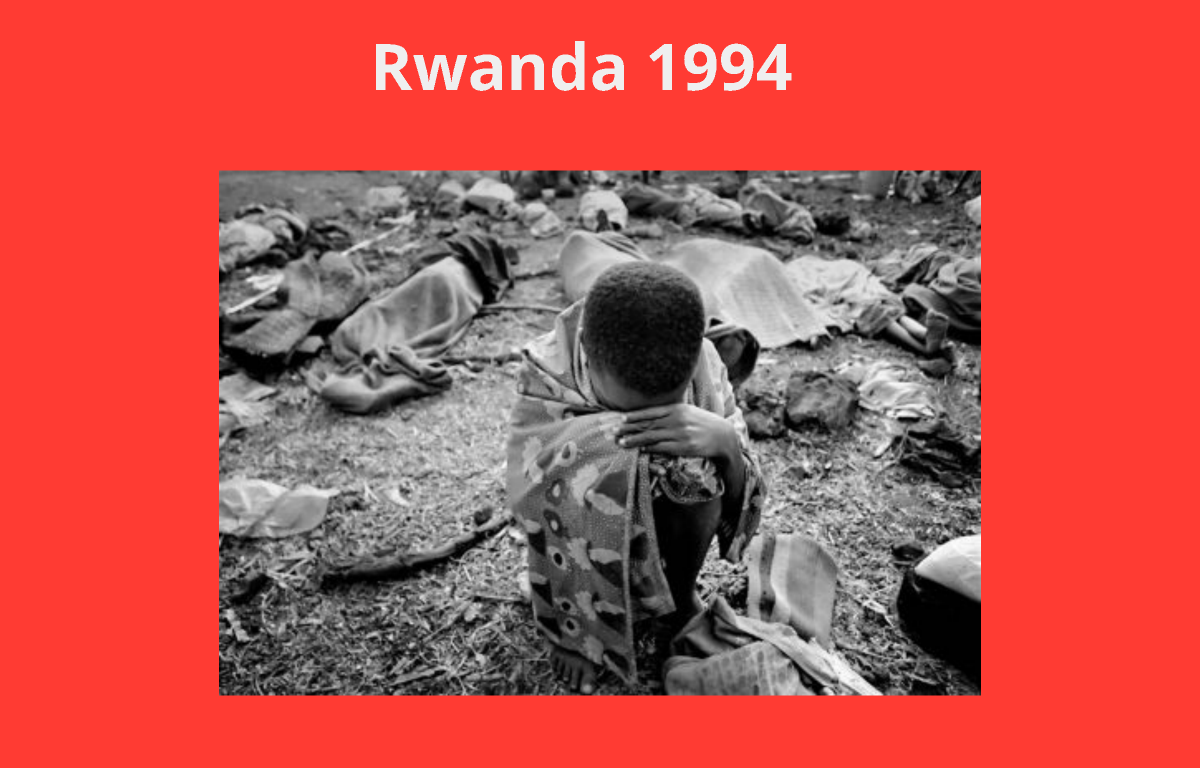

In other words, discourse is constitutive of power and the media, by virtue of its overwhelming control of discourse or of the major discursive spaces, is powerful. But the problem with hegemony is its instability. It is in a permanent state of flux. It is never stable because it is not amenable to being secured by law or force. To keep it stable requires permanent creation and addition of new arguments and the articulation of same across the spaces involved. What this means is that with the media is hegemony or power but a very unstable form of power. This situation makes it inadequate to point out one or two cases of sensationalism or lack of balance and conclude from there that the media escalates conflict. That is the sort of fairy tales some pseudo analysts were circulating about how the media incited the genocide in Rwanda or is fuelling Syria until Anthropologist Robbins came up with a more solid explanation/understanding of how the Rwandan genocide came about.

Contrary to media incitement, he traced it to Rwanda’s political and economic position in the global political economy, its colonial history, the collapse of the price of coffee following US withdrawal of subsidy on coffee, how World Bank and International Monetary Fund policies exacerbated this, how global interests of Western powers, particularly France as well as the interests of international aid agencies and Western attitudes towards Africa played out to unleash the cauldron, creating a situation into which various conflict parties were plugging into from their own standpoints. Interestingly, none of the major scholars who worked on the theory that media reporting could act as an autonomous provocation agrees with the hypothesis. All their findings have been substantiated numerous times by subsequent analyses, including what one of them calls fairly intense scholarly investigation of the ‘CNN Effect’. Beyond the scholars, all the key state officials interviewed in Britain and the US dismissed it as well, saying that media reporting only exercise any influence where the government has no line of reasoning in place as yet. ‘CNN Effect’ has thus since been a limping theory, unable to fly.

In other words, there can be no denying that the media could influence the way a particular crisis develops but this does not happen in the direct, automatic manner that most people think. Readers are even more important in making a media report to have escalatory impact or not than any other factor(s). That power of the audience is what explains why some newspapers die off because people simply refuse to buy and read such papers, for whatever reasons.

The media is always an instrument to be taken over and used by those who control its major segments at any point in time. If the media is not complicit in exacerbating conflict in the manner popularly assigned it, then what is the task for the civil society in conflict sensitive reporting?

The challenge is consensus building and/or conscientisation of the populace along popular democratic aspirations. That is the job that political parties should have been doing. Unfortunately, Nigeria has not had political parties with roots in the civil society and a record of consensus building on subjectivity, citizenship, rule of law and the likes. Without that and, therefore, without a citizenry that are on the same page on these practices, the ease with which interpretation of media content can differ has remained mind boggling. That is what turns up as the complicity of the media in conflict.

Insisting on a distinction between media exacerbation of conflict and media – conflict interface is important because it is the failure to draw such fine distinctions that led to miscalculations such as the erroneous campaign against hate speech which the Federal Government has now capitalized upon to roll out an anti-social media bill. The challenge for civil society organisations working on conflict sensitive reporting is to get on with drawing up modules on consensus building in the larger society. It is such modules as may be circulated in selected audiences that will blunt the escalatory potentials of national and global media reporting of conflicts in Nigeria, not forlorn hope for objective reporting because newsreporting is inherently escalatory where the society is not on the same page with itself in terms of redlines when it comes to subjectivity, citizenship, rule of law, amongst others!